Could These Evangelical Democrats Change the Party?

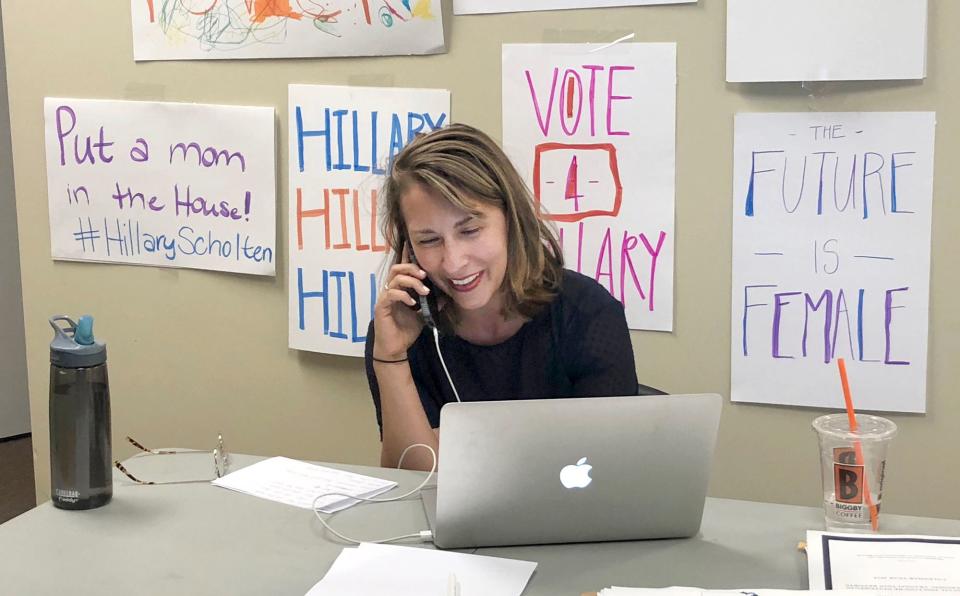

When Hillary Scholten decided to leave her job as a civil rights attorney to run for Congress, there was no question what her party affiliation would be. She had been a policy adviser in Barack Obama’s Department of Justice, quit in protest of President Donald Trump’s immigration policies and has long been a registered Democrat.

After moving back to her home state of Michigan, she called up a local party strategist to discuss running. The two met for coffee and the strategist seemed impressed. Scholten had started her career fighting against housing discrimination on behalf of people living with HIV/AIDS, many of whom identified as LGBTQ. Later, she worked as an immigrant rights attorney at a local legal aid center. Her credentials on the progressive wing of the party were deep.

The conversation took a turn, however, when Scholten started talking about her faith. She’s an evangelical Christian, and it was clear the strategist saw her overt Christianity as off-brand for a Democrat.

“We’ll just bury that,” Scholten recalls him saying.

She decided to run anyway, putting her in a small but apparently growing group: evangelical Christians running for office as Democrats.

While the religious affiliations of candidates aren’t tracked as closely as those of voters, Robb Ryerse, political director at Vote Common Good, a left-leaning organization trying to mobilize faith voters against the reelection of Donald Trump, estimated that there are roughly a dozen evangelicals running for political office as Democrats in 2020. In 2018, he estimated there were two or three.

Christina Forrester, founder and executive director of Christian Democrats for America, said her organization has gotten around 100 calls from candidates wanting to run for offices up and down the ballot as openly Christian Democrats in the two years since the 2018 midterms. Between 2006 and 2018, she guesses she got less than 30. “It has been a huge, huge spike,” she said.

If they succeed in winning over some fellow Christians, evangelicals like Scholten could help chip away at the Republican Party’s hold on white religious voters, particularly in swing states like Michigan. Even a tiny shift in that vote could have huge consequences. In 2016, 81 percent of the state’s roughly 1.3 million evangelical Christians voted for Trump, who won there by less than 11,000 votes.

But as they enter the fray, they face a challenge: getting their own party to pull the lever for someone running as a Christian.

“The fundamental fear that some Democrats have is, ‘Are you trying to take the party back for Jesus?,’” said Ryerse.

In Scholten’s district, the stakes are high: A year ago, she jumped into the race for the open seat in the state’s 3rd Congressional District, which is currently held by Republican-turned-independent Justin Amash, who isn’t seeking reelection. Long a conservative stronghold, Michigan’s 3rd district has become increasingly competitive in recent years, and Democrats see it as a potential flip in 2020. According to the campaign’s polling, Scholten is in a dead heat with her likeliest Republican opponents, who face off in a primary Tuesday.

In her case, she ignored the advice to bury her faith. Scholten is part of the Christian Reformed Church, a progressive evangelical denomination, and grew up, as she puts it, attending church "twice on Sundays and once on Wednesday.” Though she believes in the separation of church and state, her religious background drives much of her civic activism. “It was a big part of who I am and it continues to be to this day,” Scholten says.

But she also isn’t running specifically as an evangelical: She thinks that word has become too politically loaded. She identifies, in public, simply as “Christian.”

This new crop of candidates represents a brand of evangelicalism that looks less like the one espoused by leaders like Jerry Fallwell and Paula White, and more like that of former president Jimmy Carter, whose Christianity pointed him toward a more liberal strain of politics. “He saw his faith as really about serving the poor,” said Marie Griffith, director of center for religion and politics at Washington University in St. Louis.

But in American politics, the white evangelical movement has been solidly associated with the Republican Party since at least the 1970s, when religious groups like Fallwell’s Moral Majority and Concerned Women for America entered the political fray, in part to oppose school desegregation and second wave feminism (and with it, sex education and the constitutional right to abortion). Ronald Reagan, a divorced former actor, seized on that agenda to siphon religious votes from Carter, a former Sunday school teacher whose personal faith ran deep. In 1980, Reagan proclaimed in a speech that “religious America is awakening perhaps just in time for our country’s sake.”

White evangelical voters abandoned Carter in droves for the GOP, and that alliance has only solidified over time. (Black evangelicals, who have a long history of political engagement going back to the civil rights era, did not follow the same path; they overwhelmingly identify as Democrats, though don’t always align with the party on social issues.) Three quarters of white evangelicals supported Donald Trump in 2016 and their support for him remains high. But his approval among this group has dipped in recent months.

It’s not clear that this will translate into more votes for Democrats—defectors could stay home or vote third party—but there are at least some signs of change. Forrester of Christian Democrats of America said that her organization’s Facebook group has had “a lot of evangelical converts” join since the election. In the 2016 presidential election, 16 percent of white evangelicals voted for Hillary Clinton; in a recent survey, 17 percent said they would vote for Biden.

That could bode well for the small but growing number of religious candidates embracing the more liberal evangelical tradition embodied by Carter. In Georgia, the Rev. Raphael Warnock, a pastor at the evangelical church where Martin Luther King Jr. once preached, is running for U.S. Senate as a Democrat. In Missouri, Christian pastor Cori Bush is running for Congress. In Colorado, evangelical immigrant rights activist Michelle Warren, having fallen just short of making the ballot in her U.S. Senate bid this year, is already planning another run.

Often, these candidates have views that largely align with core progressive positions like a woman’s right to choose, marriage equality, action on climate change, immigrant rights and an expansion of the social safety net. Some have won high profile endorsements. Warnock was endorsed by Stacey Abrams and led the Democratic field in fundraising; Bush was endorsed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez; and Scholten has the endorsement of Senator Elizabeth Warren and the progressive organization Emily’s List.

But the backing of Democratic heavyweights doesn’t guarantee support from progressive voters, many of whom view religion with skepticism. In a 2019 poll, 44 percent of Democrats said churches and religious organizations "do more harm than good in American society." A large majority of Democrats said "liberals who are not religious" have too little or just the right amount of control over the party. Only 15 percent said they had too much. Last year, the Democratic Party passed a resolution explicitly embracing atheists after lobbying from secular groups.

Some progressive voters interviewed for this story worry that overtly religious candidates, even Democrats, will inevitably blur the line, established by the First Amendment, between church and state. “It needs to be utterly and completely separate,” says Andrea Geralds, a pro-choice, “hardcore constitutionalist” from Michigan who does not live in Scholten’s district. “There is no middle ground for me.” Even when candidates of faith say they unequivocally support the First Amendment, Geralds remains unconvinced. “As far as I'm concerned, they're probably lying,” she says. She is less distrustful when it comes to other faiths. “When people say, ‘Well, are you saying that about X religion? No, I'm saying it about evangelicals, because evangelicals are actively trying to harm people in my country.” She says that if given the choice between a progressive evangelical candidate and a Republican, she would stay home.

Wil Schweitzer, an independent in Georgia who believes abortion is a private matter and people who are LGBTQ deserve equal rights, is similarly skeptical about Warnock’s senate run. “When I see ‘Reverend’ beside a name that is asking to be elected into a position of power, red flags go up,” he says. He said he will not vote for Warnock in the state’s special general election this November.

Like Scholten, some religious candidates have moved away from calling themselves “evangelical” because the label, as popularly understood, no longer aligns with their values.

Pastor Bryan Berghoef, who is running in Michigan in the district next to Schoelten’s, once considered himself evangelical but stopped identifying personally with the term a decade or so ago. He isn’t surprised that some voters are uncomfortable. “They've only seen the conservative, ugly side of it,” he says.

Berghoef is running in a red district that is more tolerant of—and arguably demands—policy positions that could easily sink a candidate in states like California or New York. He is pro-choice, but believes that reducing the number of abortions, through progressive policies like expanding access to health care and providing a living wage, is an important goal (a once mainstream position that Bill Clinton described as abortion being “safe, legal, and rare”). Berghoef is popular among local Democrats, in part for his long record of advocating LGBTQ rights and racial justice. In November, he will face off against Republican Bill Huizenga, who is currently under investigation for ethics violations.

Politically, religious candidates must walk a fine line between being true to their religious convictions, which can sometimes give rise to more centrist positions, particularly on social issues, and alienating a progressive base that has swung decidedly leftward.

In 2018, Tabitha Isner, an ordained pastor and a Democrat, ran in a deep red district in Alabama. Isner is a member of the Christian Church (Disciplies of Christ), a progressive church that welcomes LGBTQ parishioners and clergy. But when Isner, who supports gay rights, was asked at a campaign event about a baker’s right to refuse service to gay customers, she admitted that she wrestled with the question. “I said, ‘Well, this is hard,’” she recalls. “I struggle with that as a person of faith, not because I would ever discriminate against gay people but because I understand the value of religious freedom.”

She was skewered for it in progressive circles. “I lost five gay friends who just thought it was outrageous that I would try to empathize,” Isner says. “We have a real chip on our shoulder as a party about Christians.”

Of course, with a second Trump term on the line, the possibility of cutting into the president’s evangelical base could prove too hard to resist, even for Democratic voters skeptical of religion. Lori Goldman, founder of Fems for Dems, a political action committee in Michigan that seeks to elect progressives, said her organization would support any candidate whose policies align with progressive values, though she acknowledges deeply religious candidates give her pause. “I get a bad taste in my mouth,” she says. “People have done the most egregious things in the name of religion since the beginning of time.”

For her part, Scholten talks about her faith openly on the campaign trail. “I think that voters have a right to know the person who is representing them,” she says. The local leader who expressed skepticism at first eventually came around, too. “He said, ‘You're a Christian mom who is a civil rights attorney and wants to run as a Democrat in western Michigan,” Scholten recalls. “‘This is either going to be the flip of the century, or we're going to go down in flames.’”