Even During Queen Elizabeth II's Reign Violence Was Central to the Empire

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Queen Elizabeth II alongside President of Kenya Daniel arap Moi on her arrival in Nairobi, Kenya, Nov. 10, 1983. Credit - Tim Graham Photo Library/Getty Images

“Queen Elizabeth was a life well lived; a promise with destiny kept and she is mourned most deeply in her passing. That promise of lifelong service I renew to you all today.” Charles III, delivering his first public address as king, framed his future while honoring the nation’s longest reigning monarch as only a son and heir can. Using time-worn images he gestured to the queen’s wellsprings of soft power—Britain’s “precious traditions,” “unique history,” and “family of nations”—which are now his.

His speech pregnant with meaning, the king was defining a legacy that he now inherits. This legacy, already fraught with controversy, is a deeply imperial one. No sooner had the queen drawn her final breath, then fault lines split, exposing further a world deeply divided over questions of whether the British Empire was a force of good or one of violent subjugation and exploitation.

For many Britons, the Queen was a steadying force, revered by her subjects for the virtues—duty, honor, and devoted service—she embodied and symbolized. Others, including those from the former empire, refuse to mourn, condemning Elizabeth II for alleged direct knowledge of and complicity in British colonial crimes, including murder and torture. Some see her complicity as more subtle, obscuring through decades of reassuring rituals and acts of omission the systemic racism and extreme violence upon which Britain’s imperial power, and hers, depended.

How do we begin to assess Queen Elizabeth II’s fraught imperial legacy? How do we separate self-professed experts piling on with hagiographies or misinformed critiques from facts as we currently know them? Recently, some historians, myself included, have offered revisionist accounts of the empire, describing in detail the centrality of violence to the nation’s colonial project during Queen Elizabeth II’s reign.

Here’s some of what we know. When Queen Elizabeth II ascended the throne in 1952, she was constitutionally responsible for hundreds of millions of colonial subjects spread across some 70 colonies, territories, and mandates. Britain’s economy was in tatters and independence demands were exploding.

The nation’s postwar recovery, however, and Big Three (with the U.S. and Soviet Union) status hinged on the exploitation of colonized subjects across the globe. Conservative and Labour governments alike would not concede to urgent calls for freedom, instead sacrificing wartime guarantees of self-determination on the altar of national self-interest.

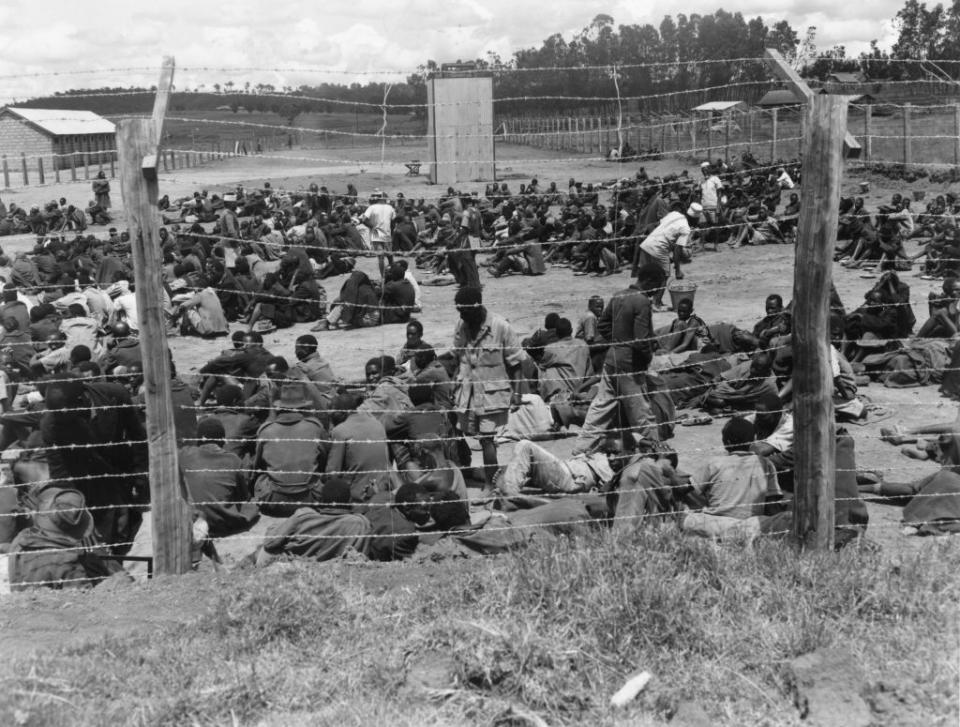

Recurring, brutal end-of-empire conflicts thus marred the first thirty years of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign. Beginning in Malaya, then in Kenya, Cyprus, Nyasaland, Aden, and Northern Ireland, British security forces moved through the empire and acted in the Queen’s name, unleashing wide-scale detention without trial and illegal deportations. In Malaya and Kenya, they forcibly relocated hundreds of thousands of subjects into barbed-wire villages where forced labor and starvation were forms of colonial control. In each conflict, kill squads were deployed and populations terrorized. In Cyprus, journalists called interrogators HMTs, Her Majesty’s Torturers.

At the time, successive governments denied allegations of systemic violence, claiming any instance of brutality was isolated, the fault of individual colonial officials, so-called bad apples.

Read More: Britain Can No Longer Hide Behind the Myth That It’s Empire Was Benign

What we know now, however, reveals a much different reality. Beginning with her first prime minister Winston Churchill, the queen’s ministers not only knew of systematic British-directed violence in the empire, they also participated in its crafting, diffusion, and cover-up, which was as routinized as the violence itself. They repeatedly lied to Parliament and the media and, when decolonization was imminent, ordered the widespread removal and burning of incriminating evidence.

A fundamental question remains. How much did the Queen know at the time, and what did knowing mean? There is no extant documentary evidence directly linking her to knowledge of systematic violence and cover-up in the empire. Nor were her weekly meetings with the prime minister recorded. The evidence we do have suggests that she, like the public, was told any instance of brutality was an unfortunate one-off, and minor colonial officials were to blame.

Over three decades, serious and repeated accusations of systematic crimes committed in her name, however, abounded, with those from Cyprus and Northern Ireland reaching the European Commission on Human Rights. To suggest a monarch who was renowned for her deep knowledge of foreign policy and assiduous work ethic was completely in the dark seems implausible.

In fact, the queen was the guardian of Britain’s imperial past and curator of its present and future. Like her predecessors, she self-consciously wrapped herself in the empire, deploying images and symbols, as well as the language of fictive kinship, to project claims to British benevolence and exceptionalism. In so doing, she detracted from all that was being carried out in her name while beckoning her colonial subjects to revere her.

The queen finessed the empire’s dissolution by recasting the familiar kinship motif. Under her obsessive direction, the British Commonwealth, or “family of nations,” rose from the empire’s ashes to become a vehicle for perpetual global influence. Comprised almost entirely of former British colonies, the Commonwealth was a triumphant coda to British exceptionalism. The matriarch’s family had “grown up” while her power endured.

One thing is for certain: Serious crimes happened on the queen’s imperial watch. King Charles III seems well-aware of global demands for a British colonial reckoning based on protests and appeals from former colonial peoples, as well as the abundance of recent evidence unearthed by historians. He will need to abandon his paternalistic ways, breaking from the tradition his mother held so dear and revising the “unique history” of imperial benevolence that she cultivated and affirmed for seventy years. The alternative—to simply carry on—will only hasten the monarchy’s demise.

God Save the King.