Everglades Cape Sable seaside sparrow holds water management hostage

A persistent conflict in the Everglades drives blood pressures as high as the rainwater. The cause? Every few years, Mother Nature dumps too much of the wet stuff in the wrong place.

The water problem pits the diminutive Cape Sable seaside sparrow against:

The health of three of the state’s greatest estuaries (Florida Bay and the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers)

Two Native American tribes (Seminoles and Miccosukees)

Lake Okeechobee, known as the “Liquid Heart of Florida”

The proper hydration of land in western Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade counties — an area larger than Delaware.

At stake is the precious long-range status of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, a $23 billion fix to South Florida’s ecological plumbing problems. For Treasure Coast residents, the problem is also tied to Lake Okeechobee discharges to the St. Lucie River.

How to move the water, where to put it and how long it takes ruffles the feathers of the tiny little endangered bird that calls the Everglades home, as well as the tribes and several government agencies caught in the middle.

Moving water through the Everglades

The tangled web of water management in Florida is like planning a wedding reception with 100 guests: No matter where you seat confrontational relatives, someone ends up angry.

The Everglades system is enormous. It ranges from Shingle Creek and the wetlands of Walt Disney World to the archipelago of Islamorada in the central Florida Keys.

Before developers and farmers began sectioning off Florida’s pastures and marshes, the natural drainage system encompassed 11,000 square miles. Federal and state partners are tasked with trying to fix one of the largest and most complex ecosystems on planet Earth.

When there’s too much water on the land between the southern rim of Lake Okeechobee and the northern border of Everglades National Park — an area called Water Conservation Area 3 — it puts the bird at odds with the:

Army Corps of Engineers

Department of the Interior

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

National Park Service

Endangered Species Act

South Florida Water Management District

Miccosukee and Seminole tribes

How do I feel about the bird?

If you’ve been reading my columns for years, you know my relationship with the bird goes like this:

20 years ago: I hated the sparrow and wanted it to move. I thought it caused more water to be discharged to sea via the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers because it couldn’t flow south.

3 years ago: I felt sorry for the little bird and softened my criticism. I still wished it would move. After all, birds have wings, right?

Now: It’s complicated. But maybe the time has come for us to move what’s left of them.

How does too much water affect the sparrow?

The sparrow is barely 5 inches long. Fewer than 3,000 are estimated to live in the wild.

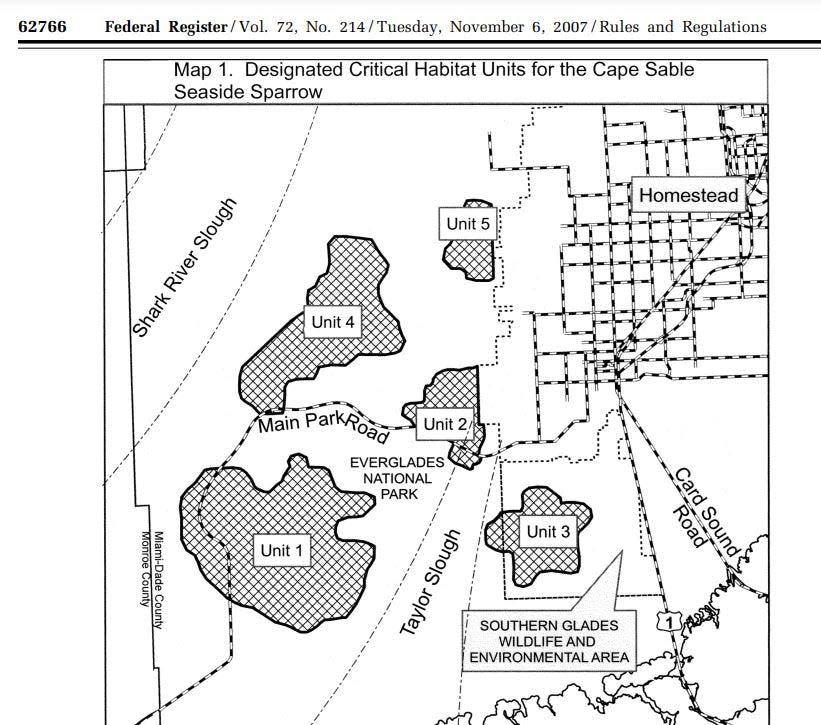

Its life cycle depends on muhly grass on the calcium-rich marl plains in the eastern Everglades of Miami-Dade County. It’s why the entire known population resides completely within the borders of Everglades National Park.

Water sheeting across these lands can be no deeper than about 6 inches, lest it push out the birds or keep them from nesting in the winter months.

A recurring problem happened again this fall, when the area got abnormally high amounts of rainfall in September and November. For over six months, water managers kept more rainwater than usual in WCA3 to keep it from flooding the sparrow’s nesting habitat. But that flooded the tribes’ lands.

The Miccosukees pleaded for state and federal officials to move the water off their lands and relieve flooding on natural tree islands. When that didn’t work, they took to social media. Tribe members stood waist-deep in the River of Grass, holding signs that read, “Open the Gates!”

On Nov. 28, the Army Corps opened the gates along the edges of WCA3 and the Tamiami Trail. That moved water through Shark River Slough and out into the Gulf of Mexico.

What do we do about the sparrow?

This lopsided conflict in Everglades restoration pits decisions about the management of a single species against the management of water for many people. By law, the Endangered Species Act always supersedes moving water, even through man-made stormwater treatment areas, as in the case of the sparrow and the Everglades snail kite.

High water in WCA3 is going to be a problem every four to five years. It will flood the Miccosukees and Seminoles. It will drown the remaining tree islands, of which over 68% are already destroyed, a mid-1990s study estimated. The water HAS to flow south into Florida Bay and Shark River.

Two other threats to the Cape Sable seaside sparrow loom. Sea-level rise caused by climate change could swamp nesting lands in a few decades. More immediately, the growing problem of invasive pests in the Everglades could wipe out the sparrows.

Pythons, tegu lizards and Nile monitor lizards — already spreading across South Florida — will eagerly gobble up sparrows and their eggs faster than the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service can render a biological opinion.

Fortunately, the sparrow didn’t appear on the list of newly extinct species released in October. However, its recovery plan has yielded mixed results.

Should we gather up the handful of tiny birds we have left and house them somewhere else in pseudo-suitable habitat? If we don’t move the birds, will we ever be able to “send the water south” from Lake Okeechobee, which could end discharges to the St. Lucie River?

It may be time to rescue the birds for their own good. That will also allow us to move water where nature intended it to go.

Ed Killer is a columnist with TCPalm. This is his opinion. Email him at ed.killer@tcpalm.com.

This article originally appeared on Treasure Coast Newspapers: Everglades Cape Sable seaside sparrow holds water management hostage