Evers' Year of Mental Health initiated important conversations. Investing in strategies could take years.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Six months to see a therapist, workforce shortages, astronomical counseling bills, sick people languishing in jails, younger children raced to the emergency department for suicide attempts, higher and higher rates of substance use disorder.

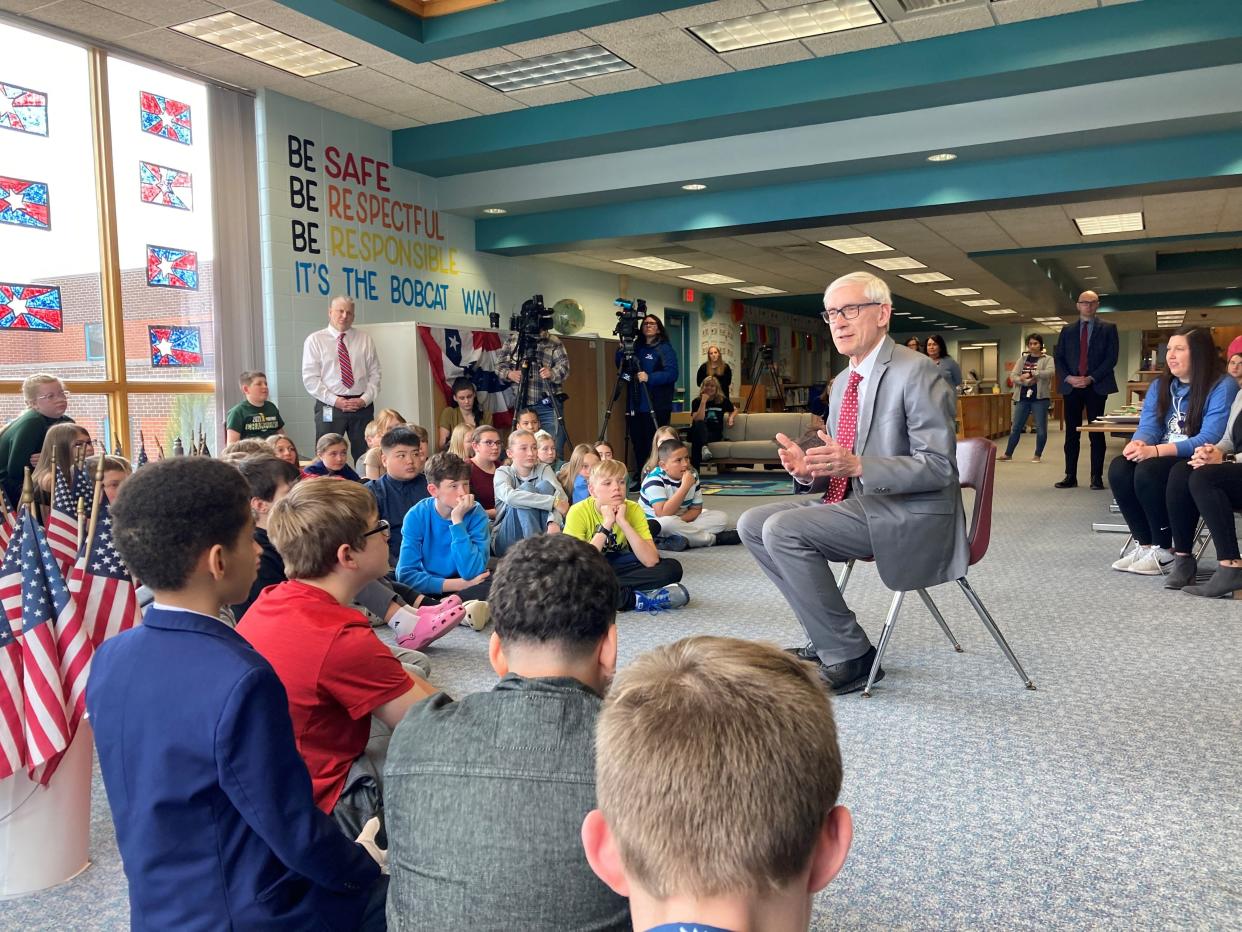

The surge in mental health needs pushed leaders across the state into action. Gov. Tony Evers declared 2023 the “Year of Mental Health” in February and proposed $500 million in mental health programming over the next two years.

In March, a roundtable of mental health stakeholders gathered from National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Wisconsin, Children’s Wisconsin, Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers and the Office of Children’s Mental Health, along with Rep. Paul Tittl, R-Manitowoc, chair of the Committee on Mental Health.

They discussed investing in sustainable school-based mental health counseling, reducing wait times to see mental health professionals, funding mental health courts, and addressing workforce shortages and delays in obtaining mental health-related licensures.

“I’m for supporting just about anything to get more access to mental health,” Tittl said.

Cut to July 5, the day Evers signed the final $99 billion 2023-25 biennial budget published as Senate Bill 70, and few mental health-related items survived sweeping legislative cuts by the Republican-controlled Legislature.

Wisconsin public schools will see more funding for school-based mental health. However, items that would have emphasized prevention, better access to care, more youth crisis stabilization facilities, and wraparound services for people experiencing mental health disorders ended up on the scrap heap.

That has mental health advocates and professionals across the state thinking of ways to reframe the needs of the community in future budgets and policies.

And the needs have never been greater. Amy Herbst, vice president for mental and behavioral health at Children’s Wisconsin, said children are screening positive for anxiety and depression at record rates, and younger children are being admitted for suicide attempts and ideation.

Herbst wants youth — and adults for that matter — to have more access to care long before they end up at the hospital.

Not addressing access to care will continue to create a bottleneck in crisis interventions, said Mary Kay Battaglia, executive director of NAMI Wisconsin.

“If we could invest in community services now, then we wouldn't have to spend so much on crisis services, which is not only more expensive, it’s traumatizing to the person living with an illness and their family,” Battaglia said.

Budget losses: Long-term school-based mental health, Medicaid expansion, Community Support Programs

Following Evers’ proposed mental health provisions, the Wisconsin Office of Children’s Mental Health identified 10 budgetary items important to children’s access to mental health services. Those included funding for psychiatric residential treatment facilities and youth wellness networks.

“They were nearly all rejected, including the ones that would have allowed us to fill holes in our system of care for kids,” said Linda Hall, director of the Office of Children’s Mental Health.

That’s a problem, said Herbst, who referenced the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study that found about 44% of high school students felt persistently sad or hopeless in the last year.

Hall hoped Legislature would see the benefits of permanent school-based mental health funding. And while the state is putting $30 million into schools for mental health services, a majority of that funding comes from pandemic relief dollars that won’t carry over to the next budget.

It’s also nearly a quarter of what Evers requested in his initial proposal.

“It’s a source of funding we can’t rely on going into the future,” Hall said.

Evers had proposed expanding Medicaid, a move that “would have brought $1 billion into our state,” said Hall, but as they have done for years, Republicans declined to expand Medicaid. That expansion would have funded much of the Office of Children’s Mental Health list of recommendations and given access to financially strained parents in need of mental health coverage.

Battaglia, of NAMI Wisconsin, said she was disappointed that Legislature rejected funding for Community Support Programs (CSPs), which would have put $40 million in community health services over the next two years. Counties and tribal agencies across the state have CSPs in place to better support people experiencing mental health disorders. It’s a preventive measure to help people struggling with illness to keep them out of crisis facilities and jails, and prevent homelessness.

“If we don't invest in the community service, which is a more dignified way to help and support those folks, we end up spending a lot of money with police and Winnebago (Mental Health Institute) and carting people across the state and dealing with crisis,” Battaglia said. “We really need a medical response to a medical crisis, instead of a law enforcement response to a medical crisis.”

Budget wins: short-term school-based mental health, 988 investments

Funding for school-based mental health services will increase from $10 million to $30 million over the biennium, a move that many stakeholders see as a win.

“You're meeting the child or the adolescent in their environment where they spend most of their time during the week, and you're not pulling them out of school,” said Maria Perez, a licensed psychologist and vice president at Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers. “And so being able to have dollars routed to youth in particular is very encouraging.”

Herbst agreed, and said she feels grateful for the bipartisan effort of supporting youth mental health. “It’s absolutely made a difference,” she said.

Battaglia said the state’s investment in 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is a major win and speaks to the Department of Health Services’ robust media campaign over the last year. Wisconsin has seen the second-highest increase in call volume in the United States since the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline recast its 10-digit number last July.

The state has also seen a major jump in certified peer specialists – individuals with lived experiences in mental health and substance use disorder services – which has helped ease some workforce demands.

That push for certified peer specialists is the product of conversations and collaboration across the state, Battaglia said.

Collaboration across mental health agencies key to workforce growth, future budget wins

To address the ongoing mental health crisis, efforts among providers have been collaborative, rather than competitive.

“There’s less competition than I’ve ever seen. We’re all aligning together,” Perez said. “There might be agencies that do things better than we do, or there might be things that we do better than anyone and people are referring to us.”

“I can tell you in communities where people are partnering on behalf of kids and their mental health, we’re getting more done,” Herbst said. “We’re getting to kids sooner and having greater success.”

Herbst added, “We want mental health to be treated like physical health, and we need parity when it comes to funding.”

Support for mental health has increased in the last few years as a result of the way people talk about their struggles, especially young people, Herbst said. Young people tend to be more comfortable talking to medical professionals about depression and anxiety, which creates a ripple effect across the community.

Herbst hopes future funds can go toward qualified treatment training programs, or QTT, which would bring more mental health trainees to the state of Wisconsin, especially where child psychiatry is concerned. QTT programs allow trainees to work at clinics and hospitals full time with benefits to fulfill the 3,000 clinically supervised hours required for state licensing. Without QTT programs, trainees would likely volunteer those hours while working a second job. Acquiring the hours without a QTT program takes longer, Herbst said, and sometimes people quit before they complete their hours.

Allowing future therapists, social workers and psychiatrists to train in-state increases their likelihood of staying put in Wisconsin.

Herbst, Hall and other stakeholders are also working with the state to improve the licensure system, so that people can get mental health-related licenses in a timelier manner. Right now, it can take many months to process licensure applications for professionals transitioning to Wisconsin from another state, a result of understaffing, backlog and the general volume of applications.

Perez also sees QTTPs as a game changer, adding that other successes, such as the federal push to give coverage to Medicare beneficiaries seeking licensed professional counselors, took nearly a decade of coordinated advocacy. Those conversations, Perez said, "led to legislative change, statutory change."

Meanwhile, Battaglia will hold out hope that the state moves to better fund Community Support Programs, which would give people struggling with mental health disorders a range of community services that meet their needs.

"Politics is a slow machine. Everyone knows mental health is important. We're talking about it when we didn't talk about mental health much before," Battaglia said. "Funding is not there this year, but this was the year of talking about mental health. It's good groundwork for us to continue on."

Brittany Truong of the Journal Sentinel contributed to this report.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Central Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Wisconsin state budget falls short of robust mental health provisions