'Everybody who came back had a tale': Jacksonville WWII POW tells his for Pearl Harbor Day

On that Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, John Connelly was a baseball-crazy 16-year-old, the youngest of eight Irish-American siblings, growing up in the tight confines of Ironbound, a working-class neighborhood in Newark, N.J., ringed by foundries and railroad tracks.

Oh, he knew what was going on, halfway around the world in Hawaii: Japanese planes had attacked Pearl Harbor, killing more than 2,000 Americans and kicking off the country's entry into World War II.

Still, on that day, he didn’t think much about it: “We were stupid kids in the city," he said 82 years later from his Jacksonville home.

But it soon began to sink in. "We went to school Monday, they sent us home. Why why why? And that was the reason: A lot of the teachers went out and had volunteered right away.”

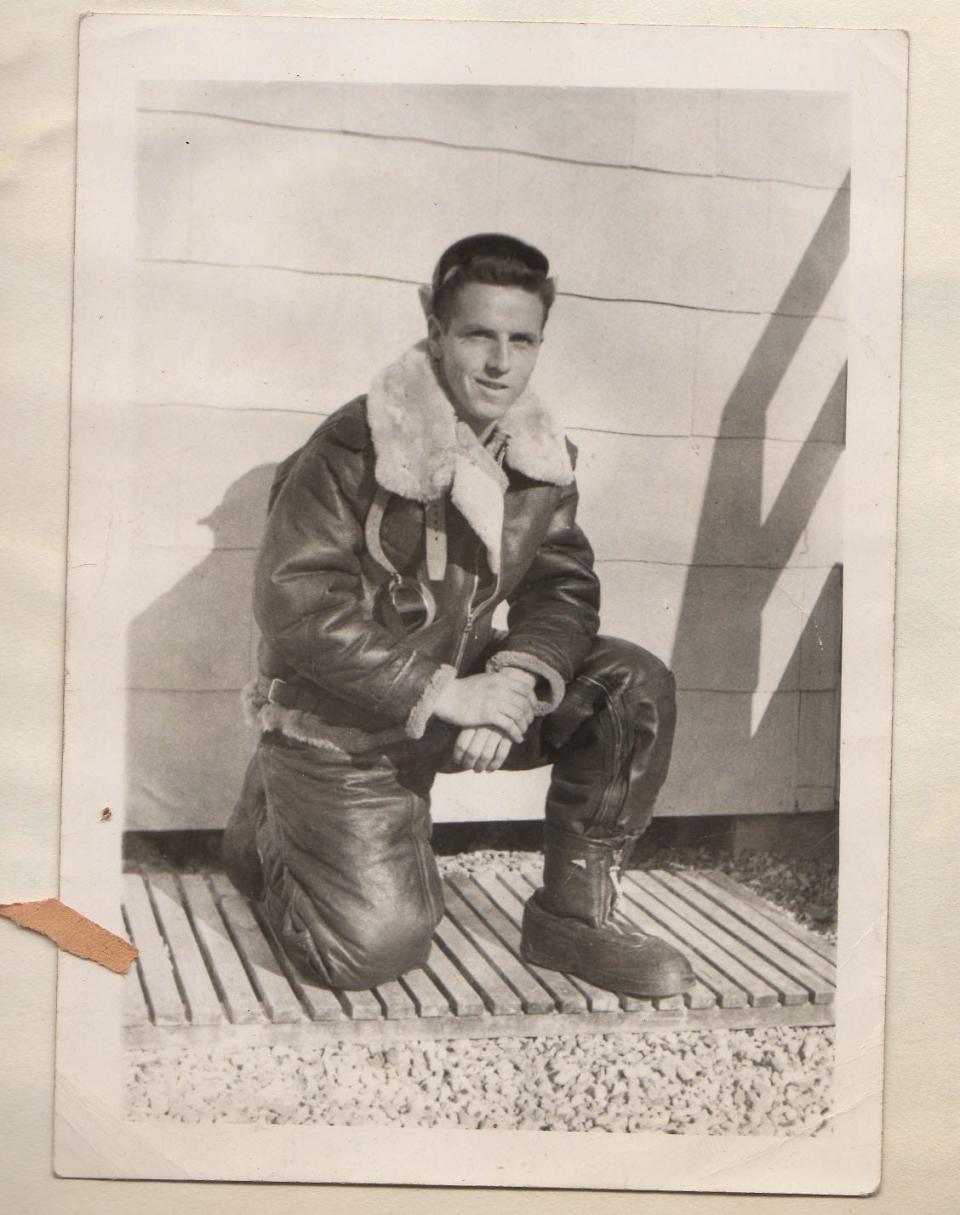

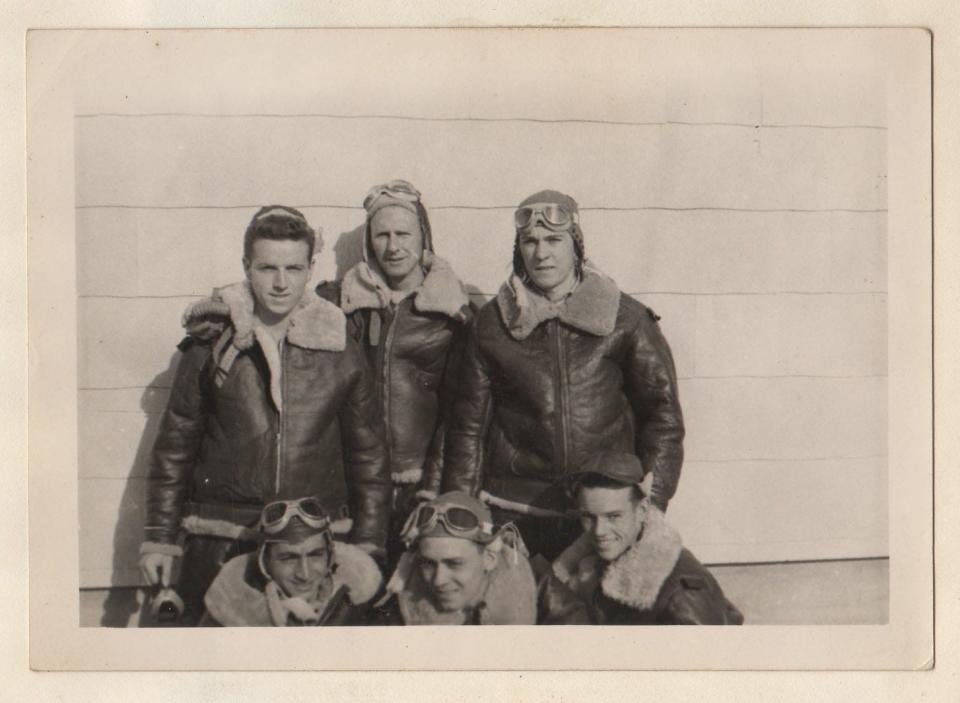

Two years later, after graduating from his Catholic high school, it would be Connelly's turn to go war when he was drafted into the Army Air Corps, to his relief. "I would have felt like half a man if I wasn’t in what was going on," he said.

He became part of a crew of a brand-new B-24 Liberator bomber that flew the northern route from the U.S., over Canada and Greenland, landing at an air base in Scotland on another momentous day: June 6, 1944. D-Day.

Connelly, now 98, was just 19 years old then.

Shot down over Germany

On July 4 he flew his first mission. It was terrifying facing enemy fire. He was manning the tail gun that day and, after getting back safely, he found that anti-aircraft flak had torn a hole in the plane, right near his head, just above his left shoulder.

“So much excitement, you don’t even know it," he said, shaking his head, all these years later.

On the 24th, the crew flew their eighth mission, with Connelly on the right waist gun of the bomber called the Cape Cod Special II. As they neared their target in Munich, the plane was hit by flak and started to lose altitude. Flying low, it was struck again over Freiburg.

Well aware they wouldn't make it home, the pilot and co-pilot aimed for neutral Switzerland, hoping the crew could bail out there. They jettisoned the bomber's guns, trying to lighten the load, and the crew jumped at the last possible chance.

“My advice to you if you’re ever in that situation, don’t look down more than once, because you’ll find 12 excuses not to jump," Connelly said.

He floated into a tree, stuck in branches about 15 feet off the ground. He was fastidious in those days and had put razors in his pocket in case of future grooming needs. Instead, he used them to cut himself free, then began walking down an empty road, thinking he was safely in Switzerland.

He wasn't. He was a few miles short in the Black Forest of Germany. And he was soon captured by civilians from a nearby town, Todtmoos.

He recalls an older man stepping forward and telling him, “I German prisoner, England, World War I. You now German prisoner.”

Connelly ended up being sent to a German POW camp, then — as Russians advanced from the east — going on a forced march of 52 days and hundreds of miles during a brutal, hungry winter before ending up in an international prisoner camp.

He was 5-foot-8, 140 pounds when he left for the war. Lean. By the time he was liberated, he was probably about 110 pounds. Starving.

Pearl Harbor remembered

Connelly turns 99 on Jan. 17. His mind is sharp but he moves carefully now, often with the help of a walker. To think, he says, that he used to be an athlete, a centerfielder and leadoff batter who dreamed of being a big-league baseball player.

Along with World War II veteran Fred Pappas, he'll be a guest of honor Sunday at the Pearl Harbor Remembrance Luncheon presented by the nonprofit We Can Be Heroes Foundation. Tickets for the catered event at VyStar Veterans Memorial Arena are $10.

On the home front: The forgotten Germans of Camp Blanding's Stockade Number 2

Connelly said that he adjusted to civilian life pretty well.

He went to college at Seton Hall on the G.I. Bill, then threw himself into work — 55 years running a real-estate, insurance and appraisal company in New Jersey. He got married, had five kids, four of them daughters, and after his first wife, Jeanne, died of pancreatic cancer, he entered another long marriage with his current wife, Winona, whom he met at a dance.

She has family in Jacksonville, so they moved to the city into a house they built in a subdivision not far from the airport. He hadn't talked much at all about his wartime experiences up until then, but as he began meeting members of the city's large veteran population, the stories came out.

At 84 years old, he told his war story to the Times-Union's Mark Woods, noting that he'd kept it to himself for decades. "Everybody who came back had a tale," he said then. "Who wanted to hear another one?"

Less than two years later in 2011, he traveled back to Germany to be greeted by residents of Todtmoos where he'd been captured.

Killed at Pearl Harbor: Sailor comes home to Jacksonville, 77 years, 6 months, 13 days later

A historian there, Felix Kahlert, had tracked him down from that earlier article and wanted to learn more about his experiences. He showed him pieces he'd found of Connelly's bomber, which had crashed into a mountain just a kilometer or so from Switzerland.

He'd earlier sent him a small chunk of metal from the plane and two spent cartridges, which Connelly still treasures.

In 2013 Connelly was the grand marshal of Jacksonville's Veterans Day parade, riding in a truck from 1944. His fellow passengers? Kahlert and a friend of his from Germany.

Finding faith, battling dreams

During a recent interview at his home, Connelly is asked: Could he have imagined, at 19, flying over Europe, that he would one day be 98, almost 99 years old?

There's a pause that stretches to 10 seconds. And then he said, "Somebody up there liked me."

His mother wanted him to be a Catholic priest; he went to a Catholic high school and university and took his faith seriously. Later, working hard, it didn't seem to matter as much. "I became an Easter-Christmas guy," he said.

In recent years, however, it's become more important, and he started saying the rosary every day.

“So I’m in a state of grace now." He smiled. “And I pray for everybody.”

In some ways, he's glad to have gone through what he did during the war.

“I think it made a person of me, you know?” he said. “You could take adversity.”

But he has been haunted ever since, he says, by a disturbing dream: He's in a strange town, surrounded by grotesque, menacing people — “the ugliest people you ever saw in your life.” He runs from them, but they trap him, and as he’s lying on his back on the ground looking into their hideous faces, he defends himself the only way he can, by kicking at them.

“Then my wife comes and wakes me up,” he said.

The dream comes less often as he's gotten older. “Now it might be like twice a year. Back then," he said, "it was more often.”

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Jacksonville World War II POW tells story ahead of Pearl Harbor Day