‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

“Once this broke, there was a sort of mania in Staunton.”

His name was Roland Lazenby, and after the initial shock wore off that a rapist was at large in the city and his own employer had to be pushed into publishing anything about the crimes, he did what a reporter does. He took to the street and talked to people. He talked to women. He talked to Black men, who he intuited might be feeling targeted by police and the white community.

And he began to take walks at night, easily identifying the unmarked police cars and hanging around areas where he saw signs of heightened police presence.

“This was my first real year in journalism,” Lazenby recalled in a 2021 interview. “I think it surprised everyone” that the police and the newspaper had not reported on rapes by a knife-wielding stranger as soon as they occurred. He’s not sure who might have made that decision.

Lazenby wasn’t surprised that someone at the paper could have worked with police to hold back information about the break-ins, assaults and rapes. “The Leader in those days, you know, was often like life in the South — it was a curious mix,” he said.

Curious because, among other things, the newspaper’s crime photographer also shot crime scene photos for the police department.

That same police force was not pleased to see a Leader reporter out at night trailing them.

“They threatened to charge me with interfering in an investigation, because I was following them around at night, trying to see what they were doing and how they were going about things.”

Lazenby left the Leader early in 1980. He went on to write biographies of Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant.

“Obviously they felt comfortable withholding this information from the public. It blew up in their faces.”

All the publicity, and perhaps the greater police presence it inspired, made for a quiet August when it came to break-ins and assaults.

It wouldn’t last more than a few hours past the first day of the next month.

*

The Leader printed four stories on its front page on Wednesday, Sept. 5, 1979, with a story from Savannah, Georgia, and two with datelines from Richmond. There was even a story from London that earned a space on the afternoon edition’s cover.

The most important story of the day, though, was from Staunton, and it was buried on Page 2: “Another rape reported in city.”

The rape occurred early Sunday morning, but “police department officials asked The Staunton Leader to withhold a report until information was released by the department this morning.”

The police asked for the delay, according to the story, to protect “stake-outs at one or more points of the city” and “undisclosed leads” that remained unreported in the story. The dates of the last three rapes showed a distinct pattern: June 3, July 1, Sept. 2 all fell on weekends. How likely was it that he would strike again on a weekday after a rape, when he had not done so before?

And if they did believe he might be active, others would ask, why not warn the public?

When asked if the stake-outs and undisclosed leads had brought the police any closer to identifying and apprehending a suspect, the police spokesman answered, “I don’t know.”

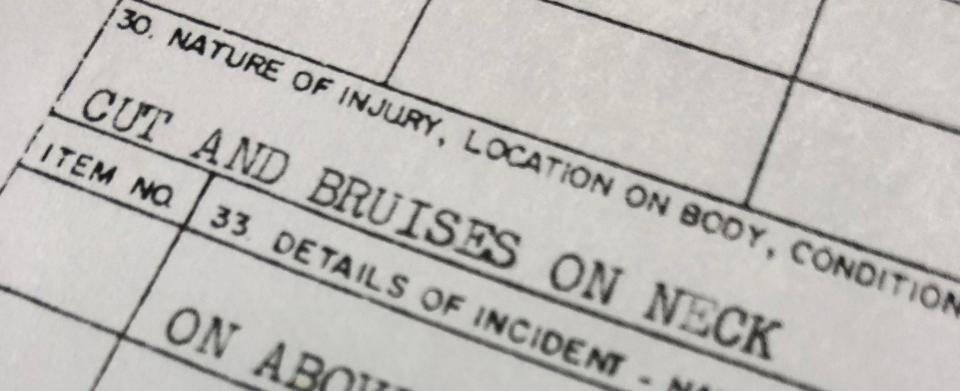

Police first said the rapist forced his way through a locked first-floor window, but curiously added a caveat in their statement to the newspaper: “The police spokesman suggested the window latch may not have been closed completely.” The detail did not appear in the police incident report.

Was it an attempt to place responsibility back on the woman?

*

Just across Central Avenue from The Leader’s office, journalists and townies, cops and detectives regularly gathered at the Different Drummer to nurse a cup of coffee and listen to the whisper-stream while they filled the room with cigarette smoke. Charles Culbertson, still stringing for The Leader, sat across the table from a female friend.

The diner’s owner, rumor had it, was a former DuPont employee from nearby Waynesboro who’d made a small fortune as part of the team that invented Formica, the durable material making up countless kitchen counters and table-tops.

The tables at The Different Drummer were wooden and linen-covered, the lighting low and friendly. In a room separate from the bar where the four stools almost always were filled, Culbertson and his friend talked quietly.

She’d been babysitting the night of Sept. 1 when the stocking mask rapist forced his way in. “Since (March) the rapist has struck again and again, and his latest attack was on another girl I know,” he wrote in his journal on Sept. 7.

They sat at a table at Different Drummer that day, and the enormity of the violence against his friend sunk in.

“[She] was babysitting when this detestable son of a bitch broke into her house, cut her with a knife, and threatened to kill the children if she didn’t stay quiet,” he wrote.

He was perturbed that the paper he worked for had failed to notify the public about the imminent danger facing single women.

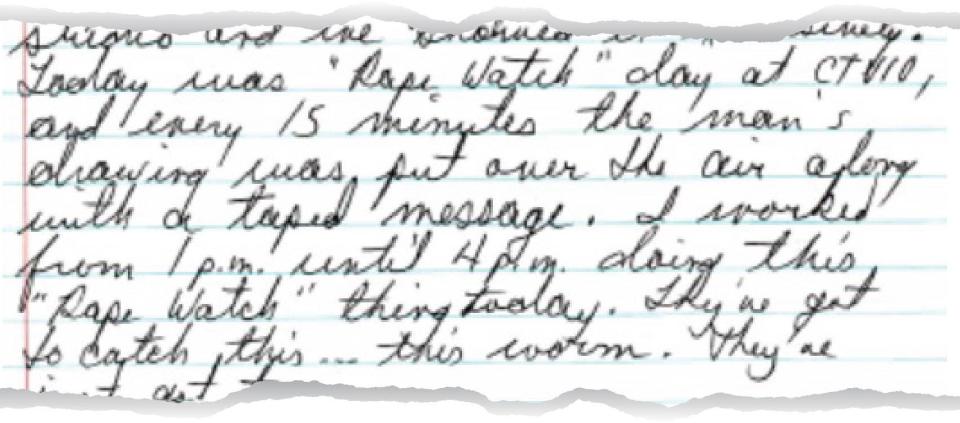

One of Culbertson’s other gigs was a regular show on local cable called “Staunton Closeup.” His September contribution was a three-hour “Rape Watch” segment from 1 to 4 p.m. that Friday, showing the police’s vague composite sketch every 15 minutes. Still, there was little to report because the police were protecting their leads.

As a young man in a small city with an intransigent police force and a newspaper just waking up to the danger to half its readership, Culbertson felt something more had to be done. His editors at The Leader had not given him the green light to write a story yet.

He needn’t have worried. A few weeks later, his cigar-smoking landlady would bring the story right to his doorstep.

*

Staunton Leader reporter Roland Lazenby’s story running above the fold in Sunday’s Sept. 16 paper amplified the concern of both white females and Black males as summer turned to fall with police no closer to stopping the stocking mask rapist.

“Everybody’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them, for that matter,” one woman told him.

Lazenby introduced the other aggrieved party in town, innocent Black men and teens who were under constant suspicion from a racist white Southern community that treated them like a menace to the public.

“[Roger] Jenkins is what you might call the secondary victim of the rapist,” Lazenby wrote. “He is a young black man, one of many who have been under uncomfortable scrutiny lately.”

“My sister told me of some blacks they’ve been pulling over because they suspect them of being the rapist,” Jenkins told Lazenby.

Another Black man, Rodney Freeman, criticized the Leader’s role in putting a composite drawing of the suspect on the front page of the paper. “There’s a whole lot of other crime too, but you don’t see them putting nobody else’s picture on the front page. … Because this man is black.”

For those comments, Freeman would find himself under scrutiny by police as a potential suspect in the case, including having his palm print, along with those of five other Black men, examined against the North New Street banister print.

None proved to be a match.

Lazenby was the first reporter to add the Mary Baldwin rape from March to the list of the crimes of the stocking mask rapist, and the first to write that there’d been an arrest in an earlier case.

People Against Rape counselor Marney Gibbs said that nationally only one out of 10 rapes are reported. “While she doesn’t want to suggest that 30 people have been raped in Staunton, she does feel there is a strong possibility that more than three women have been assaulted,” Lazenby wrote.

Perhaps the most succinct indication of the public’s rising anxiety, Lazenby wrote, was the posted reward for information leading to the conviction of the rapist. On Sept. 12, the People Against Rape established a reward of $130. A day later it was $250. By the third day, it was $585.

On Sunday, the day Lazenby’s story came out, the reward stood at $785.

*

The police had finally admitted there was a serial rapist in the city.

What they hadn’t admitted yet is that they were certain the person they were looking for was responsible for an additional rape in March.

Why weren’t they mentioning it? Because they’d arrested a Black man, Gordon Smith, for that crime five months ago. He'd been living at a homeless shelter at the time he was identified by the first rape victim. He was not charged; the police knew by the time of the second rape in June that the man was not responsible for the first rape.

But he was trapped in the bureaucracy of the state’s mental health wards and remained imprisoned in an institution, under observation.

He was still in the custody of the state when a second suspect was arrested Sept. 17.

Theodore Gray, 23, a Staunton resident who worked for the U.S. Forest Service, was charged with the September rape after the victim saw him walking on a city street.

Gray lived on the west side, a mile away from the area around the women’s college where the rapist was operating. Police declined to say on what street Gray was spotted by the victim.

When asked if Gray was also suspected in the earlier rapes, Commonwealth’s Attorney Ray Robertson’s answer was curiously distant. “That would only be speculation, and I won’t speculate on an ongoing case.”

What Robertson also wouldn’t speculate on is that he thought Gray was an unlikely candidate for the rape charges, and that the most recent arrest only compounded a troubling situation he felt was spinning out of control.

Two groups of people were afraid to go out at night — white women, who feared being hunted by the stocking mask rapist, and Black men, who feared being hunted by the police.

And for centuries in America, when white women were afraid of Black men — it was always clear who would pay with their livelihoods, their liberty, their lives.

Two Black men had already been arrested in Staunton in what was already seeming to be a bungled and racist police investigation.

Two weeks later, with Gray in jail and the first forgotten suspect lost in the mental health system at Southwestern State, the real stocking mask rapist proved he was not yet behind bars.

— Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a storytelling and watchdog coach for the USA TODAY Network. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

NEXT UP IN 'THE STOCKING MASK'

The panic that gripped the town was real. “It was just an unsettling feeling, just not really knowing. And I guess we’d always been so comfortable,” said one woman.

White people had been comfortable, at least.

“1979 was no different than any other year for the last 400 years on this continent,” said Staunton native and Black resident Jerry Venable. “Black men have always had a target on their backs.”

Venable may not have been a target of police. His height was closer to seven feet than six, and much of the year he was touring as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters. But his friends felt the heat, and by the fall you couldn’t walk down the street of your hometown alone without a cop nipping at your heels asking what you were doing out.

“That year,” Venable said, “the circumstances just exposed things for what they were.”

PART 1: Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

PART 3: Cops admit predator is at large. Staunton women told to use ‘can of hair spray’ for defense.

PART 4: ‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

PART 6: ‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

PART 7: Women make demands. A psychic makes predictions. And a Virginia city holds its breath.

PART 8: Things go ‘round and round’: Two unlikely sources help police close in on Staunton predator

PART 9: After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Reporter discusses coverage of Stocking Mask Rapist case as fears rise