'Everything Everywhere All at Once': Here's why kindness matters on infinite Earths

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s so tempting to just give up.

Living in a world caught in perpetual chaos and peril, sometimes it all feels like too much. There are pressures that come from your job, your society, your government, your religion, your family and especially yourself — the hopes and dreams never realized, the paths not taken, the potential squandered, the infinite what-ifs.

We’ve all heard the call, the nagging urge to take all that confusion, frustration and doubt and pile it together, like so much seasoning on an everything bagel that’s both mightily cosmic and baked into each of us.

It can be all-too-appealing to embrace the empty carbohydrates of nihilism, the comfort of oblivion.

The late, great Kurt Vonnegut, as he so often did so well, offered a retort to this line of thinking. It’s plain as day in his 1965 novel “God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, or Pearls Before Swine.”

Taking reservations: 10 restaurant openings that brought something special to the Jersey Shore in 2022

Feeling merry and bright: Here are the top 12 most heart-warming Christmas songs of all time

“Hello babies, Welcome to Earth,” Vonnegut wrote. “It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. On the outside, babies, you’ve got a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies – God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

Vonnegut’s work found its proper spiritual successor this year not on the page, but at the movies. “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is a film that is radical in its silliness, revolutionary in its kindness. Existing as either maximalist minimalism or minimalist maximalism, this is art that doesn’t gaze into the abyss, it giggles at it.

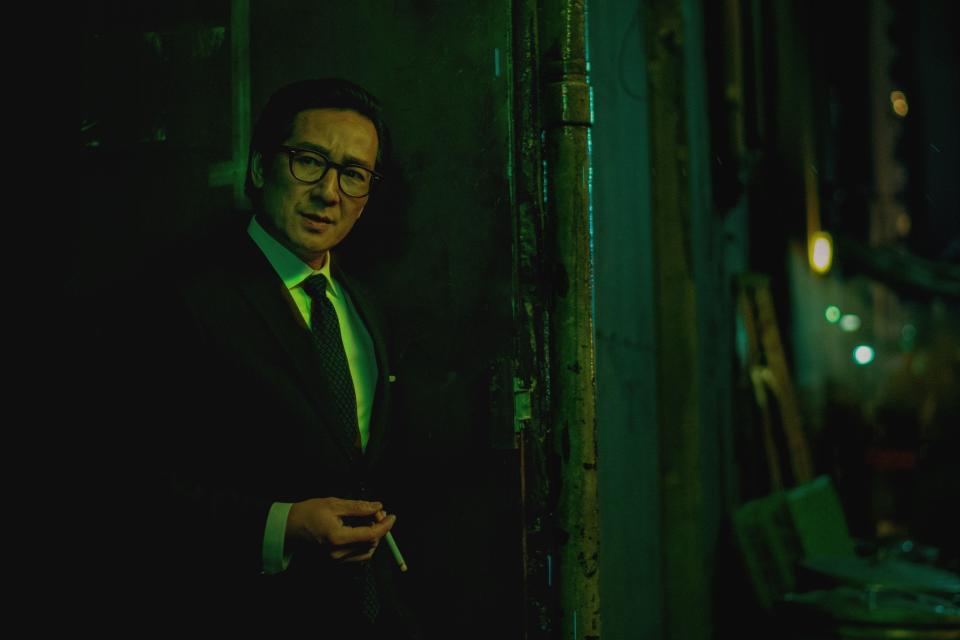

Written and directed by Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert — the “Turn Down for What” music video masterminds turned tandem auteurs — “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is simultaneously simple in its premise and brilliantly complex in its execution.

On its face, it concerns Evelyn Wang, played by Michelle Yeoh, who is a laundromat owner, wife, mother and daughter facing looming problems from the Internal Revenue Service.

Evelyn is busy managing her business and her visiting father (James Hong), staving off tax issues and hard conversations with her husband Waymond (Ke Huy Quan), making final preparations for a Lunar New Year party and continuing to not see eye-to-eye with her adult daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu).

That’s when, like fellow grumpy and beleaguered party-planner Bilbo Baggins, adventure arrives at Evelyn’s feet. There’s a crisis on our infinite Earths, and it’s up to Evelyn to bring peace, stability, and maybe even joy, to the multiverse.

Sweeter than ‘Strange’

Of course, multiversal disruption is nothing new at the movies — in fact, it’s all the rage, thanks to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

The concept was popularized for mass consumption in Sony’s 2018 animated smash “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” (not yet technically part of the MCU). Benedict Cumberbatch’s heart surgeon-turned-wizard Stephen Strange then opened the portal to infinite fan service opportunities in 2021’s “Spider-Man: No Way Home” and 2022’s “Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.”

Audiences thrilled as Strange and Spidey crossed paths with different versions of themselves and other characters from the pages of Marvel comics — but those adventures couldn’t help but feel hollow in comparison to “Everything.”

While the concept of parallel realities conveyed a “we’re-all-in-this-together” inclusivity in “Spider-Verse,” by “No Way Home” the idea was merely deployed as a cheap plot mechanic, a hand-waving way of getting Tom Holland, Tobey Maguire and Andrew Garfield on screen together as their iterations of Peter Parker.

By “Madness,” the multiverse was reduced to a nihilistic gimmick deployed for cheap pops, allowing director Sam Raimi the thrill of having beloved characters killed off in gruesome fashion and then moving on before ever having to deal with the consequences.

“Everything” is just the opposite. In the face of a bizarre, indecipherable existence in a boundless expanse of time and space, Daniels argues that our smallest actions, and the motivations behind them, are what matter most. To acknowledge the utter absurdity of life, the universe and everything — and then still act with love regardless is profoundly brave. It’s heroic. It’s everything.

Daniels’ work is one of the boldest cinematic visions to come along in this generation. They combine science-fiction, martial arts, slapstick comedy and adventure in their heady proceedings, while keeping their story firmly rooted in matters of the heart.

The cast’s quartet of industry lifers — Yeoh, Hong, Quan and Jamie Lee Curtis — alongside Hsu (in what ought to be a star-making role) turn in instantly-iconic performances that guide the viewer through Daniels’ psychedelic silliness.

When the film’s primary iteration of Yeoh’s Evelyn is told “you’re living your worst you” and she embraces her mission to save the multiverse anyway, she invites all of us along for the ride. Maybe we are all our worst selves. Maybe everything has turned topsy-turvy. That’s no excuse to give up, or to give in.

Quan’s Waymond, uttering what may well be his universe’s equivalent of Vonnegut’s “you’ve got to be kind” directive, says it best: “The only thing I do know is that we have to be kind. Please, be kind — especially when we don’t know what’s going on.”

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: Everything Everywhere All at Once is a film you need to watch