Everything That Goes Into Making a New Balance Sneaker

Every New Balance sneaker created at one of the company’s five New England-based factories moves quickly, stopping at each worker for an average of just 22.5 seconds. But those 22.5 seconds come full of precision, both mechanically and individually, as New Balance still churns out over 4 million sneakers—roughly a quarter of overall production—from the United States, the only major sneaker brand making product domestically.

As the Boston-based company continues to grow—it plans to add a sixth factory to its stable in Massachusetts and Maine—don’t expect that 22.5 seconds to slow anytime soon.

While all five current New Balance domestic factories produce sneakers, the Lawrence, Massachusetts site serves as the flagship factory, perched overlooking the Merrimack River in a converted mill building.

The latest sneaker designs may come from the company’s new headquarters in Boston three miles from either the Harvard campus or famed Fenway Park, but the engineering and production know-how lives on floors three through five at the Lawrence facility, all perched atop the second floor factory and in the shadow of the building’s four-sided mill clock with dials, the world’s largest of its kind and, at 267 feet high, second only to London’s Big Ben for the tallest clock in the world.

But that clock doesn’t tick in 22.5-second increments—that’s the role of the 220 workers producing a shoe every few seconds on the second-floor factory.

A finished sneaker begins with raw materials, from synthetics to rubber to leather. New Balance starts with the leather and the newest addition to the factory floor, a numerical control cutting machine from Italian manufacturer Comelz.

The Lawrence factory runs one 6 a.m.-to-2:30 p.m. shift daily, with three main production lines all working on identical products. Lately, the classic 990v5 has filled all three production lines in different sizes and colors. To start the 990v5 process, the factory floor needs flats full of pigskin hide. That’s where the NC cutter comes in handy.

Every piece of hide comes into the factory pre-dyed. Each hide requires individual inspection from a worker to highlight both defects and uniquely high-quality areas. The machine then reads the marks placed by the worker, using an algorithm to determine the best cutting pattern on each individual hide to eliminate the use of imperfections, maximize dimensions, and use the highest quality portion of the hide, such as the belly for pigskin, for the proper locations on the sneaker.

“The cutter does an assessment on the hide and then tells the machine how to cut it,” says Manny Gomes, manufacturing supervisor. “It will automatically populate the points the workers circled as issues and match it with the sizes needed. This is huge for us.”

Using 10 cameras, each with a small angle of view, the system digitizes the work area and three lasers provide optimal viewing projection on the leather. Then the machine cuts and workers assemble the pieces.

New Balance still uses a traditional hydraulic synthetic cutter for the non-leather portions of the shoe, standardizing the process and cutting more than one sheet at a time.

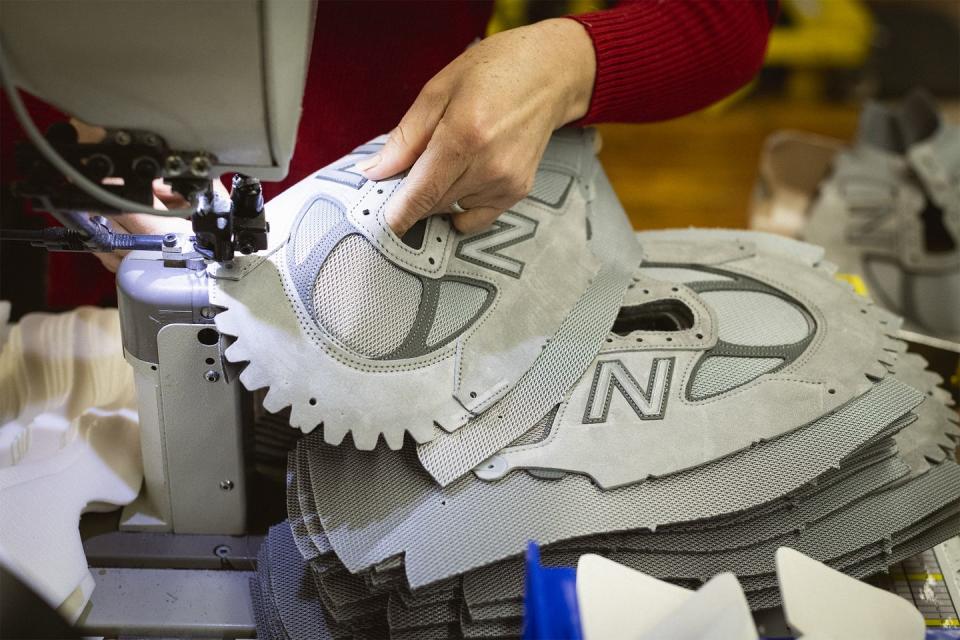

Once all material gets cut and portioned based on size, it moves to the pre-fit section of the factory. For the 990v5, this means 32 pieces enter the assembly progression. As part of the 55-step process, the pre-fit step-by-step adds the “bells and whistles” to the leather and synthetic materials, including saddles, foxing, and heat transfers.

Most of the pieces are computer stitched, making it, as Gomes says, “mistake proof” while eliminating variations.

Once the still-flat upper gets adorned with the needed embellishments—the New Balance “N” logo takes anywhere from 70 to 102 stitches, depending on the size, for example—the shoe then moves to the closing section of production.

This is where the upper joins with the tongue, collar lining and foam. The foxing—the area that joins the outsole to the upper—must get prepped. “This is a highly skilled operation that is critical,” Gomes says. “If it is not correct, it is crooked.”

From closing, the shoe travels to assembly. The upper, no longer lying flat, but with some shape starting to resemble a shoe, gets wrapped around the last, a mechanical form of hardened plastic that mimics a foot. “Everything is going to start to take the shape of the last,” Gomes says. “You pull and stretch the material over the last and then cement the entire bottom.”

Then comes time for the outsole to join the upper. The soles get sprayed with a hot-melt cement and a flash activator activates the cement. The entire shoe is then placed in a sole press machine that includes a bladder that pushes the sole into the upper, using the cement to lock the two pieces together.

Once the shoe finishes its pass through the sole press, the last is removed for reuse and the shoe gets laced, tagged, cleaned, and inspected. It even passes through a small metal detector to check for any unwanted material. When it clears final quality control, the shoes get boxed and sent to distribution. In all, it’s a 55-step process that takes three hours from cut to pack.

The other side of the Lawrence factory floor contains a slightly different process: a complete custom production line for the company’s NB1 program that allows customers to customize lifestyle sneakers and baseball cleats with chosen colors, embroidered messages, and materials.

“Every pair is very time consuming and it takes a lot of skill to make the system so you don’t make a mistake,” Gomes says. “There are millions of options. You can even pick the color of the eyelet. You have to be flexible enough to know different operations.”

The former mill building houses more than a factory floor, with multiple levels of engineers and designers supplementing the headquarters 35 miles away. And expect a new wave of production to kick off inside the factory, too, with one floor dedicating space for dozens of 3D printers from Formlabs and a computerized Stoll knitting machine that will eventually produce New Balance shoes with just two parts: 3D-printed resin to construct the outsole and a knit upper, cutting product inventory waste and storage.

Katherine Petrecca, general manager of footwear, innovation design, located in Lawrence, says that by owning their own factories, New Balance can more quickly “drive new industry standards and elevate performance on our own terms.”

That first happened with TripleCell. New Balance entered a partnership with Somerville, Massachusetts-based Formlabs in 2017 to create a 3D printing production system that included a new material.

“It was not the machines, it was the materials,” JF Fullum, senior design director, says about the hold up in sneaker 3D printing and the new Rebound Resin the company debuted in June. “We need durability and rebound weight. There is nothing like Rebound Resin in printing.”

Pairs of 990s featuring a TripleCell 3D-printed outsole of Rebound Resin—a photopolymer resin in the heel sold out in a day upon their June 28 launch. Expect more in September, all made in Lawrence, including a new TripleCell model with additional 3D pieces in the forefoot. Then comes the future of New Balance with prototypes already in the works on a new TripleCell product hopefully to the market in 2020 with a 100 percent 3D-printed outsole and a knit upper, two elements coming from the Lawrence facility.

Katy O’Brien, engineering manager, manufacturing innovation and a MIT graduate, leads the charge to set up the new production area, ramping up to show off new knit and 3D creation techniques and a completely fresh way to manufacture sneakers.

“We have hit the trifecta of high performance, digital manufacturing, and made in the USA,” says Fullum. “It is achievable.”

You Might Also Like