Everything You Need To Know About Russia’s (Possibly Fictional) Super Heavy Rocket

During the tail end of 2019, the outspoken head of the Roscosmos Space Corporation, Dmitry Rogozin, triumphantly announced to the press in Moscow that his organization had just approved the design of Russia’s first super-heavy rocket.

“Last week we accepted the preliminary design of the super-heavy launch vehicle,” Rogozin told RIA Novosti news agency. “My deputy Aleksandr Lopatin was appointed to lead the work...”

Начинаем планировать расширение Технического комплекса под ракету сверхтяжёлого класса pic.twitter.com/utjAFlP90y

— Дмитрий Рогозин (@Rogozin) January 27, 2020

This announcement arrived as the culmination of several years of work by Russian scientists trying to develop the most ambitious space project since the fall of the Soviet Union. But what exactly is this Russian super-heavy rocket and does the notoriously troubled space agency have the means to pull off something this huge?

The Rebirth of the Super Heavy Rocket

According to Roscosmos's definition, a super-heavy rocket is capable of delivering at least 35 tons of cargo into Earth’s orbit. But most other companies and agencies tend to describe a “super-heavy rocket” as a vessel capable of carrying at least 50 tons or more. Past similar rockets, like the Apollo-era Saturn 5, could carry 140 tons into low-Earth orbit, which helped NASA pull off its gutsy moonshots in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Five decades later, those super rockets are back in fashion as the only realistic means of launching ambitious human exploration projects (unless space elevators or photon engines make some huge engineering leaps).

In the U.S., NASA and private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin, are already developing or launching progressively bigger rockets, crossing Russia's 35-ton, super-heavy threshold. China is also inching toward a vehicle, called the Long March 9, that will be able to transport closer to 100 tons.

With so many players aggressively pursuing their super-heavy rocket ambitions, Moscow’s grown increasingly concerned that its space program was lagging. After having ceded numerous space frontiers to the U.S., Europe, China, and India in the past two decades, the Kremlin needed something to show it was still a big dog in this new global space race.

Waking a Sleeping Colossus

Two years ago this week, on January 28, 2018, the Russian president Vladimir Putin signed the long-awaited Decree No. 32, approving the development of the super-heavy space rocket.

In the following two years, Russian engineers sifted through a multitude of rocket designs that could do the job. A popular proposal was reviving the Soviet-era Energia booster, originally designed for the abandoned Soviet shuttle, but it was nearly impossible to resurrect the old rocket as-is. They’d need to make major changes.

The Energia uses a zeppelin-shaped central body that is actually a tandem of two tanks containing cryogenically cooled liquid oxygen and hydrogen propellant. The tanks feed a quartet of super-powerful engines, providing most of the thrust during its nine-minute ride to orbit. On the sides of the core stage are four kerosene-burning strap-on boosters to help at liftoff but are then discarded around two minutes into the flight.

NASA actually chose a somewhat similar architecture for its SLS super heavy-lift rocket, except the kerosene boosters were replaced with a pair of solid rockets inherited from the Space Shuttle program. But the problem with the Energia three decades later is that its components were simply too big to transport in a country much smaller and much less affluent than the Soviet Union.

Unlike the U.S, Russia has no easy sea route to haul an oversized core stage from its rocket factories in the European part of Russia, such as the city of Samara where today’s Soyuz rockets are built, to the launch site in the Far East at Vostochny spaceport. The Soviet government resolved this problem by simply paying for a custom-built cargo plane, converted from the VM-T Atlant strategic bomber. But today, without that costly option, Roscosmos engineers need to fit all major components onto rail cars, which could then pass through the narrow tunnels and treacherous zigzags of the Trans-Siberian railroad.

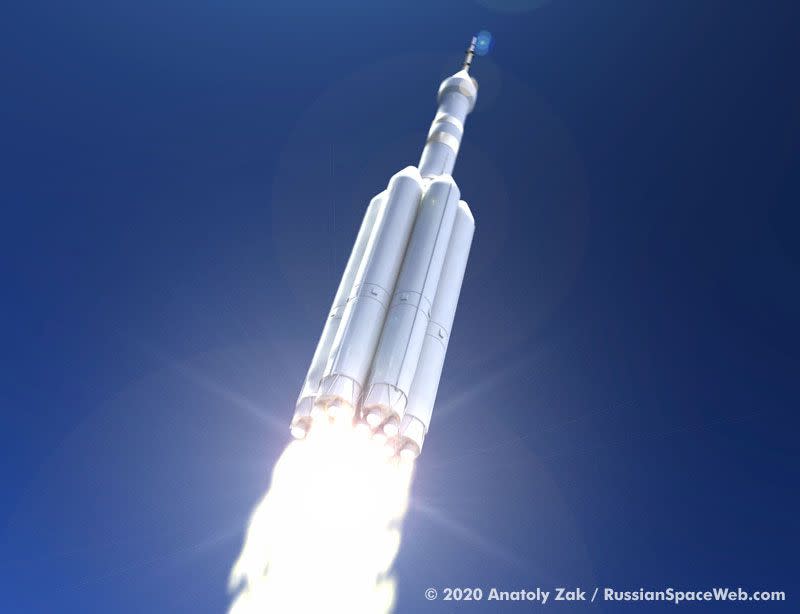

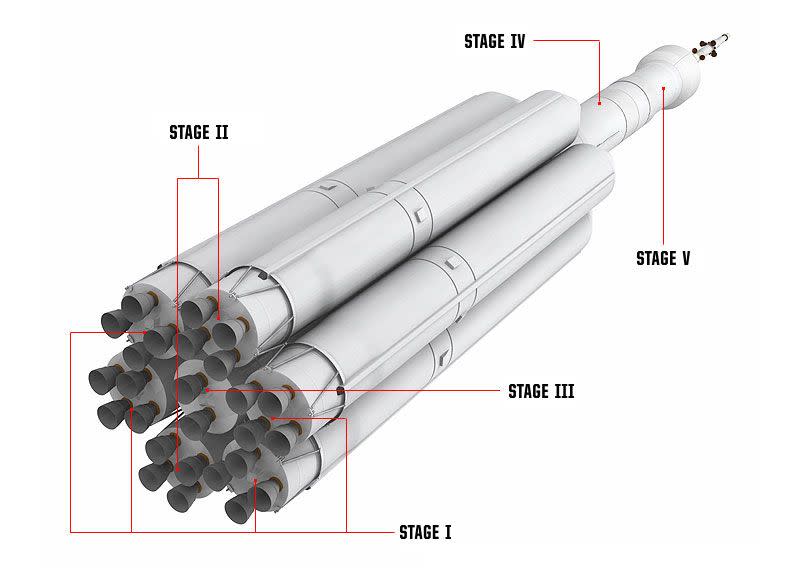

By abandoning the use of risky hydrogen fuel on the core stage and opting for the less-efficient-but-more-condensed kerosene fuel instead, engineers could "slice" the rocket into a cluster of seven boosters, each of them small enough to fit onto a rail car. A smaller hydrogen-burning stage could still be mounted at the top of the rocket with the secondary task of pushing its cargo from the initial orbit around the Earth into deep space.

This seven-booster Energia successor was renamed the “Yenisei,” after the great Siberian river.

Introducing the Yenisei

While downsizing rocket boosters seems counterintuitive when designing such a big rocket, the cluster approach does offer some distinct advantages. The big one being that each individual booster can also be used to build a medium-size space vehicle, launching much smaller but much more practical money-making missions like communications satellites. In fact, that’s exactly what Russian scientists did, naming the resulting rocket the “Irtysh,” another river in Siberia.

This approach is much like SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, which is comprised of three Falcon 9 first stages. The Yenisei ups that number with 7 Irtysh first stages.

With the Yenisei and the smaller Irtysh, the Russian rocket industry could use the same factories, machinery, and workers to pump out boosters for commercial, military, and scientific missions, spreading cost across the entire rocket family. Encouraged by the newly formed strategy, Rogozin boasted on Twitter this month that "our (super-heavy) Yenisei will cost far less than the American Space Launch System, SLS."

Наш сверхтяж будет стоить намного меньше американской SLS, но уже сейчас надо заложить решения, которые сделают "Енисей" ещё более конкурентоспособным. В этом вопросе сложно не согласиться с @elonmusk . Такие расходы на пуск сложно будет потянуть даже США с их мощной экономикой https://t.co/JOZYCbKVa5

— Дмитрий Рогозин (@Rogozin) January 17, 2020

According to Roscosmos, the Irtysh booster should begin flying as early as 2023 from the existing launch pad in Baikonur, Kazakhstan, before the Yenisei eventually lifts off at Russia's new Vostochny spaceport in 2028.

"We started planning the expansion of the vehicle assembly building for the super-heavy rocket," Rogozin wrote during his visit to Vostochny this week.

Can Russia Build it?

Russia's latest pathway to super-rocket looks sound on paper, but unfortunately, there are serious doubts that this technically feasible scenario can be implemented in real life, let alone in just eight years.

Russia’s history with delivering on big space promises is a troubled one as the country has been living in the shadow of a great Soviet legacy. Inherited from the USSR, Russia operated a diverse fleet of launchers of all sizes, funded in large part by extensive commercial and scientific cooperation with the West. Most of these joint projects were established under Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s.

But with the ascent of Vladimir Putin in the 2000s, pragmatic technocrats at the helm of Roscosmos were replaced with military officers and political appointees who had no experience in the rocket industry. Ironically, as rising oil prices gave the Kremlin plenty of cash to subsidize its space ambitions, Roscosmos has had very little to show for it. Instead, the Russian space industry has become swamped with corruption, quality control problems, inefficiency, and brain drain. So much so that during the 2010s, Russia all but lost its positions on the commercial launch market.

In addition to endless launch failures, Putin's confrontation with the West (and especially his invasion of Crimea in 2014) prompted European and American partners to minimize their dealings with Roscosmos, depriving the industry of major revenue stream. Russian space companies would from then on be mostly dependent on the roller coaster ride that is the Russian economy.

As a result, in the past 15 years of relatively stable funding, Roscosmos never put a single new rocket in operation, including the costly Angara rocket that has only flown two times. Instead, the agency mostly built modest upgrades to Soviet-era relics like the Soyuz and Proton rockets.

And these development problems plagued rockets rated for only 24-ton payloads. WIll Roscosmos really be able to field a rocket orders of magnitude larger while building new production factories, a monumental launch infrastructure, and a transport system spanning several time zones?

Re-Entry to Reality

While the possibility of building such a rocket remains uncertain at best, there’s also an even bigger and perhaps even more difficult question of what it will actually launch.

To avoid the same fate as the Soviet Energia, the new booster needs a fleet of very expensive and sophisticated spacecraft to carry, including a crewed lunar orbiter, lunar landers, and other components. Yet, right now, even incomparably smaller and simpler robotic lunar probes that Russian scientists conceived back in the 1990s are still gathering dust in assembly rooms.

In 2009, the Kremlin approved the development of a replacement to its Soyuz spacecraft, which was supposed to make its first test flight in 2015 and fly with a crew in 2018—but neither milestone came anywhere close to implementation. Instead, this ghost spaceship changed its name two times and was shuffled from one non-existing rocket carrier to another.

Now Roscosmos makes equally daunting promises to launch the first prototype of the crew vehicle, called the Orel (“Eagle” in Russian), in 2023. Work on other pieces of the Russian lunar infrastructure hasn’t even gone beyond the drawing board.

In recent years, Russia has demonstrated its ability to pull together considerable resources for big national projects, like the $50 billion spent on the Sochi Olympics. But money can't buy everything. The space program requires not only stable funding but also highly qualified and motivated workers and engineers, a wide range of technologies, test facilities, and competent management.

Hopefully, Roscosmos is learning from its mistakes, but the Putin era suggests that Yenisei is just another astronomic boondoggle in the making.

Anatoly Zak is the publisher of RussianSpaceWeb.com and the author of Russia in Space, the Past Explained, the Future Explored.

You Might Also Like