Evictions drive homelessness in NJ. Here's how a new state office is tackling that

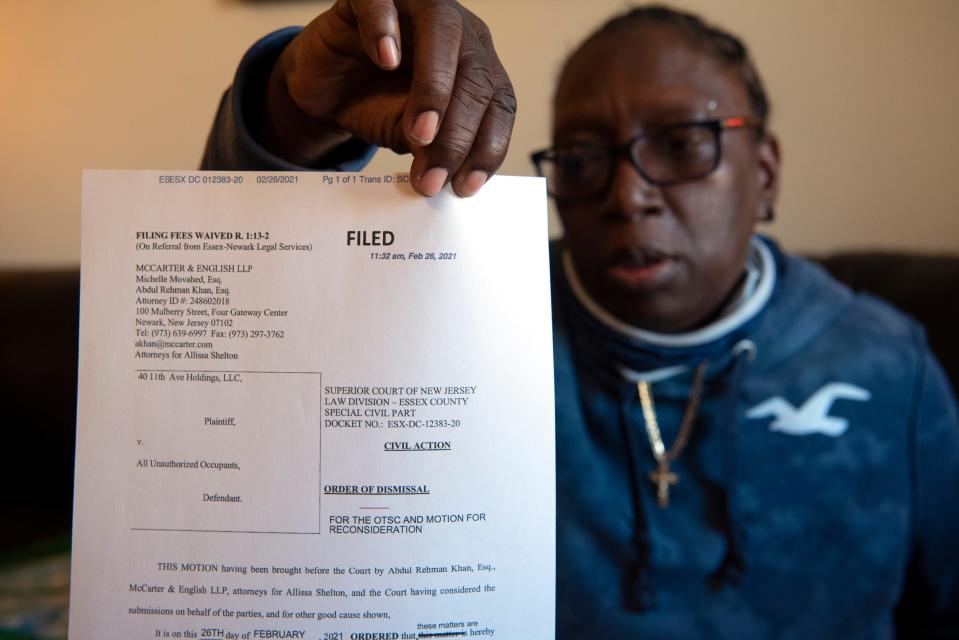

A new office designed to prevent evictions in New Jersey — one of the top drivers of homelessness in the state — has reached more than 20,000 families in its first two years, providing legal counsel, help with access to government aid and financial assistance, or guidance in navigating the court process.

Formed as part of the August 2021 legislation that wound down the state’s nearly two-year ban on evictions, the state Office of Eviction Prevention oversees a statewide operation of 48 people from 16 social services and legal agencies led by director Dean Dafis, who is also the mayor of Maplewood.

The courts share eviction filing data with the office, and the team contacts tenants and tries to reach them before trial or on their court dates.

Each county hosts at least one “resource navigator.” These are caseworkers who help those in need navigate the maze of social service supports so they can obtain rental assistance, food stamps, general assistance, disability income, crisis intervention and more.

The office took a one-year “access to counsel” pilot program, which had provided free attorneys to assist low-income renters in certain Atlantic City, East Orange and Trenton ZIP codes, and expanded it to all 21 counties with lawyers from the Community Health Law Project, Legal Services of New Jersey and Volunteer Lawyers for Justice.

During the pilot, attorneys worked with 5,100 families, and 86% of those households avoided lockouts.

In 2023, more than 10,100 families each month across New Jersey received a notice that their landlord filed for eviction — the legal proceeding that can end with a renter being locked out of the home, with the most common reasons usually missing or being late with rent or failure to pay a rent increase.

Backlog of eviction cases remains

Murphy halted most evictions through December 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which slowed the pace of eviction filings because courts weren’t hearing cases. In 2020, there was an average of 6,800 filings each month, and 2021 had an average of less than 4,000 a month. Courts are creeping back up to the pre-pandemic levels of 2019, when the monthly filing rate was 12,600.

The state is also still dealing with a backlog from the time judges didn’t hear these cases. There are more than 19,000 active pending cases, with the largest dockets from Hudson, Essex and Middlesex counties as of October 2023.

Nearly 90% of the thousands of people with whom the Office of Eviction Prevention worked have remained in their homes, 9% were relocated and 1.8% became homeless, according to Department of Community Affairs data through the first week of November.

The largest age group of people it has helped are those 31 to 55, and nearly 60% of those assisted were Black, compared with 21% white and 16% Hispanic.

The families they help are severely cost-burdened, meaning they spend a majority of their paychecks on rent.

A third of income for housing

A popular rule of thumb is to spend one-third of your income on housing costs. The median renter the office is helping spends 59% of their money each month on rent. The median amount of back rent they owe their landlords is $5,057.

Some counties have higher disparities than others. For instance, the renters in Cumberland and Salem counties have a median monthly income of $923, compared with a median rent of $1,220. Passaic County has the highest median back rent due — $9,600. Bergen County renters owe a median $6,000 to their landlords.

Dafis has ambitious plans for the future of the office, such as stopping landlords from filing in court in the first place. Even if a case is dismissed or rent is paid, the case’s existence usually leaves a stain on a renter’s record, making it harder to rent another home.

Join with a public housing authority

He hopes to partner with a public housing authority and set up a “housing help center” with counseling to help tenants having trouble making rent, inspired by work done in Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and Dallas.

In cases where public assistance isn’t enough to cover back rent, or someone is being locked out and needs funds immediately, the office is deploying so-called “flex funds” that it can get out the door quickly with minimal paperwork.

“If you’re a mom with two children and you’re on the curb and calling me and saying you need help, the last thing I need to do is ask you what your email is and send you over a packet of 26 pages of documents,” Dafis said. “What I need to do is to get you access to money right away. That’s what we’re doing here.”

To contact the Office of Eviction Prevention, the hotline is (609) 376-0810 and the email address is evictionprevention@dca.nj.gov.

To see a list of providers in your county, visit nj.gov/dca/dhcr/offices/dhcroep.shtml.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Evictions drive homelessness in NJ. New office tackles issue