Evidence for 'Planet 9' may actually show our theory of gravity is incomplete

Evidence pointing toward the existence of an undiscovered ninth planet in the solar system may actually indicate our ideas of gravity are incorrect.

Such is the conclusion of two scientists who studied the effect the wider Milky Way galaxy would have on objects in the outer edges of the solar system if gravity is described by a theory known as Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND).

Various recipes of MOND might essentially explain how galaxies rotate as fast as they do without flying apart. Typically, most scientists believe this suspicious galactic structural hold suggests the existence of dark matter — an invisible form of matter that does emit or reflect light. The idea is that massive halos of dark matter envelop and gravitationally bind galaxies together, preventing their contents from flying outward like horses on a carousel spinning way too fast.

MOND does away with the need for dark matter, instead suggesting Isaac Newton’s famous law of gravity is correct — but only up to a point. Instead, MOND suggests that, under great rotational velocities, a different type of gravitational behavior takes over. And that type of behavior applies to rotating galaxies.

Related: Astronomers weigh ancient galaxies’ dark matter haloes for 1st time

"MOND is really good at explaining galactic-scale observations, but I hadn’t expected that it would have noticeable effects on the outer solar system," Case Western Reverse scientist Harsh Mathur, who conducted this new study with Hamilton College professor of physics Katherine Brown, said in a statement.

MOND or Planet 9?

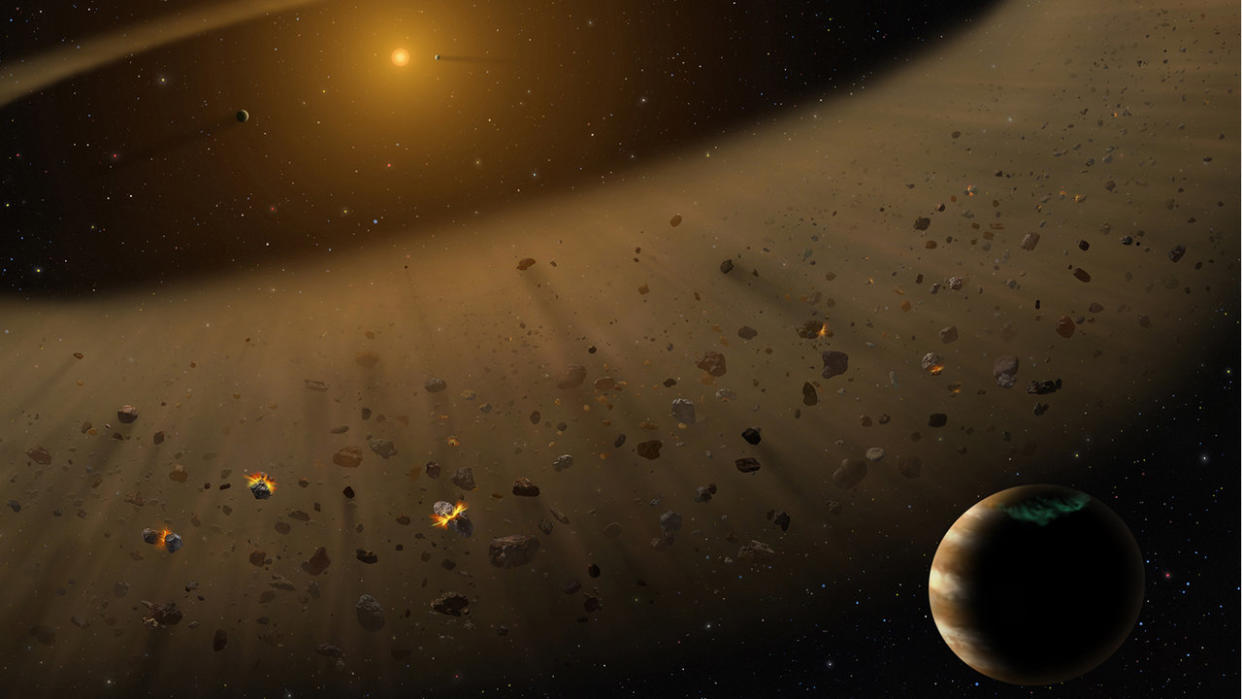

The connection between MOND and a hypothetical Planet 9 may seem odd, but it emerges from the fact that the primary evidence for this world — that supposedly lurks at the edge of the solar system — is the strange behavior of objects in a distant structure called the Kuiper belt. The Kuiper belt is a disk in the outer reaches of our cosmic neighborhood that hosts various icy bodies like comets and asteroids.

In 2016, some of these icy objects were found to have orbital anomalies and clustering unlike their fellow Kuiper belt dwellers — and this strange behavior, experts believed, could be the result of an undiscovered planet.

Strange orbits like these have revealed the presence of planets before, with Neptune found as a result of its gravitational tug on other solar system objects, but Mathur and Brown wanted to know if strange Kuiper belt orbits could be the result of something else. Perhaps those orbits could be explained if MOND is the right recipe for gravity.

"We wanted to see if the data that support the Planet Nine hypothesis would effectively rule out MOND," Brown said.

And ultimately, they found that the strange clustering could indeed be because of MOND. Mathur and Brown propose that over the course of millions of years, the orbits of some outer solar system dwellers could have been gravitationally dragged — instead of being aligned with the rest of the solar system, they find alignment with the gravitational field of the Milky Way.

Mathur said the duo found that “the alignment was striking.”

Related Stories:

— Could an 'Earth-like' planet be hiding in our solar system's outer reaches?

— Elusive Planet 9 could be surrounded by hot moons, and that's how we'd find it

— Renowned string theorist proposes new way to hunt our solar system's mysterious 'Planet 9'

The scientists themselves urge caution in assessing their findings, admitting the dataset informing this research is small and suggesting that any number of other possibilities could be correct.

"Regardless of the outcome, this work highlights the potential for the outer solar system to serve as a laboratory for testing gravity and studying fundamental problems of physics," Brown concluded.

The duo’s work was published on Sept. 22 in The Astronomical Journal.