Ex-Union Teachers Argue Dues Collection Rules Violate 1st Amendment Rights

When Chicago teachers went on strike in 2019, Joanne Troesch, a technology coordinator in the city’s schools, and Ifeoma Nkemdi, a second grade teacher, decided they no longer wanted to be part of the union.

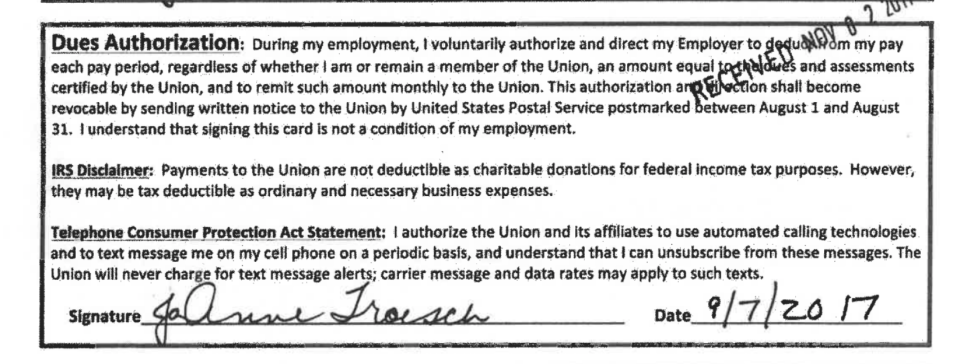

But despite their resignations, the Chicago Public Schools continued to withdraw dues from their paychecks on the union’s behalf. The union argues the deduction was legal because the educators signed a contract in 2017 agreeing to the dues.

Troesch and Nkemdi sued, and now are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to take their case. Troesch v. Chicago Teachers Union asks whether signing a membership contract sufficiently authorizes unions to continue collecting the money. The plaintiffs argue that states are denying employees’ rights with so-called “escape periods” — windows of time, ranging from 10 to 30 days, in which employees can opt out.

If employees miss that window — which National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation attorney William Messenger described as a “mandatory subscription service” — unions continue to collect the dues.

“Employees subject to these restrictions are effectively prohibited from exercising their First Amendment right to stop paying for union speech for 335–55 days each year, if not longer,” the plaintiffs argue in their petition to the court.

The Supreme Court won’t decide until October whether to hear the Troesch case, but if it does, the outcome would have an impact on 4.7 million members of public-sector unions in 17 states that have escape periods, Messenger said.

The case is the latest to argue that states and unions are skirting the court’s 2018 decision in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31. In a major blow to unions, the court ruled in that case that collecting union, or “agency,” fees from “nonconsenting” public-sector employees is unconstitutional because the money subsidizes unions’ political and policy positions. The justices said unions can’t just presume that employees have waived those rights. Some predicted the Janus decision would seriously cripple the unions’ political power, but their considerable influence over school reopenings shows that hasn’t been the case.

Making it ‘harder to resign’

Referring to the escape periods, the Troesch petition says, “The Court should not allow the fundamental speech rights it recognized in Janus to be hamstrung in this way.” But so far, the lower courts haven’t agreed. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit in Troesch, as well as the 3rd, 9th and 10th circuits, have upheld the restrictions. Messenger is also asking the court to hear Fischer v. Murphy, in which two teachers from New Jersey’s Ocean Township School District are challenging that state’s 10-day escape period. The 3rd Circuit ruled against those teachers in January.

An escape period is considered a “maintenance of membership” strategy, explained Michael Hartney, a political science professor at Boston College.

“The union has an incentive to try to make it harder to resign,” he said. “If people were dropping out like flies every year, they wouldn’t be able to budget.”

But he added that striking down these union security provisions is less important to right-to-work advocates than overturning a 1984 Supreme Court decision giving unions exclusive bargaining rights. In other words, even employees who don’t join unions in states with collective bargaining laws still can’t negotiate their own salary and benefits, Hartney said.

Unions argue that they negotiate on behalf of all teachers and other school staff, regardless of membership

Attorneys general weigh in

Republican attorneys general in 16 states filed a brief with the court in late July, urging the justices to hear the Troesch case.

“Across the country, public-sector unions have resisted Janus’s instructions and devised new ways to compel state employees to subsidize union speech,” they wrote. “When constitutional rights are at stake, this Court requires ‘clear and compelling’ evidence of waiver precisely to protect individuals from unwittingly relinquishing their fundamental freedoms.”

Union leaders argue the precedent is in their favor.

“The union feels that this lawsuit was correctly dismissed by the federal trial and appellate courts, and believes those rulings will stand,” said Ronnie Reese, a spokesman for the Chicago Teachers Union. The union and the district have until Sept. 27 to argue why the court shouldn’t hear the case. Defendants in the New Jersey case have the same deadline.

The plaintiffs in both states argue that even though they signed union contracts before the Janus decision, the court’s ruling in that case made the dues deductions unconstitutional.

But in the 3rd Circuit ruling, Judge Patty Shwartz wrote, “That is the risk inherent in all contracts; they limit the parties’ ability to take advantage of what may happen over the period in which the contract is in effect.”

Hartney said Justice Samuel Alito, who wrote the Janus opinion, might want to hear the case because he has “voiced skepticism that union security provisions outweigh First Amendment violations.”

But Chief Justice John Roberts is known for preferring incremental changes in constitutional law and might not want to take up the issue because the Janus decision was “such a shot across the bow.”