Exclusive: Efforts to resurrect the woolly mammoth to modern day reaches Alaska classrooms

The company seeking to bring back the woolly mammoth and other long-gone animals such as the dodo also wants to make sure schoolchildren's interest in science doesn't go extinct.

Colossal Laboratories and Biosciences, which has been conducting radiocarbon dating and genetic sequencing of American mammoths, has shared fossils with 55 school districts in Alaska, the genetic engineering company exclusively told USA TODAY.

The school districts get to name their fossils and can use them to learn about woolly mammoths. Radiocarbon and genetics findings related to the fossils are shared with the districts as they are finalized, the company said.

It's part of the “Adopt a Mammoth'' project to do radiocarbon dating of about 1,500 mammoth teeth, tusks and bones that are in the collection at the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

The initiative "has helped us get closer to reaching our goal of classifying the mammoth fossils in our vast collection while also getting kids interested in science and ecology from an early age,” said Matthew Wooller, a member of the Colossal Scientific Advisory Board and a mammoth researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Arizona heat: How does the state's wildlife survive record-breaking summer temps? Trucked-in water

A 'once-in-a-lifetime experience'

Two years ago, the journal Science published a study from Wooller and other researchers detailing how they used isotopes collected from the tusk of a 17,000-year-old mammoth to track its movements in and around the Arctic Circle during its 28-year lifetime.

Wooller's name and his focus of study have led to some funny moments, he said.

“It’s a totally weird but kinda cool coincidence that my name Wooller matches my study organism, woolly mammoths," he said. "In school I was sometimes mistakenly called 'Mat Woolly.'"

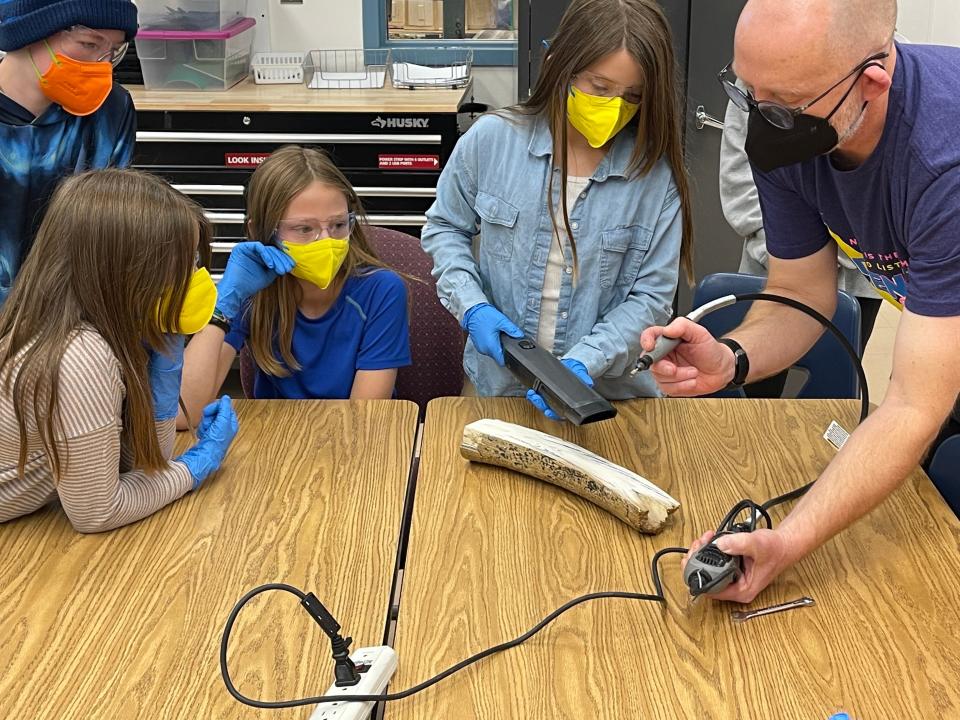

Students involved in the "Adopt a Mammoth" program are getting hands-on experience with the state's prehistoric history.

"Throughout the process, students gain ownership in the program by being able to drill their own samples and even naming their Mammoth tusk; providing a once-in-a-lifetime experience for the entire classroom," Nicholas Baker, who teaches STEM classes at Randy Smith Middle School in Fairbanks, Alaska, told USA TODAY in an email exchange.

You don't have to be a school or a student to get involved in the program. Others can donate to adopt a mammoth fossil, too.

An iconic species

Researchers aim to identify the youngest woolly mammoth to have inhabited mainland Alaska. Currently, that is held by one dated to about 11,600 years old. But other findings from ancient mammoth DNA found in permafrost cores from northern Canada and Russia suggest mammoths may have been there less than 10,000 years ago, Wooller told USA TODAY.

"We are trying to find a mammoth specimen that is this young, too," he said.

So far, researchers have taken samples from 223 of the 1,500 in the university's collection, with 25 of the 55 adopted mammoth fossils radiocarbon dated. Genetics findings from the fossils will help Colossal in its bid to resurrect the woolly mammoth.

“The radiocarbon dating of all these mammoth remains is providing us a fantastic opportunity to characterize the evolution of genetic diversity in North American woolly mammoths, and will ultimately provide a better picture of which genes were unique for this iconic species,” said Love Dalén, professor of evolutionary genomics at the Stockholm University in Sweden and also a Colossal Scientific Advisory Board member, in a statement announcing the program.

Dalén, who previously sequenced the first complete genomes of the woolly mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, is conducting DNA analysis of the mammoth specimens.

For Colossal, which has offices in Boston, Dallas and Austin, Texas, the project helps in its immediate goal of bringing back the mammoth, but also helps spread interest in science, says the company's founder and CEO Ben Lamm.

“The project is allowing us to contribute to the growth and understanding of mammoth research more broadly," Lamm said in the program announcement. "Not nearly enough research has been completed on American woolly mammoths. This is not only a great benefit for our youth, but for the entire science community.”

Genetic engineering: Scientists are trying to bring back the Tasmanian tiger nearly a century after extinction

Mammoth calves by 2028?

Two years ago, Colossal and George Church, a biologist at Harvard Medical School, announced the project to use gene editing “to restore the woolly mammoth to the Arctic tundra."

Colossal's biotech and genetic engineering teams are combining woolly mammoth and elephant DNA to recreate a next-generation mammoth that can survive in the Arctic and help restore that ecosystem, the company said earlier this year.

"Embryos will be implanted into healthy female elephant surrogates," Lamm said at the time.

Accounting for a 22-month gestation period, "we still expect our first mammoth calves by 2028," he told USA TODAY more recently.

"So far, we’ve established the cell lines, and are already making those edits in the various elephant cell lines, using identified mammoth genes," he said. "In parallel, we’re advancing the reproductive technology side as well for gestation/surrogacy."

Welcoming back other extinct species

Colossal's other de-extinction projects to bring back the Tasmanian tiger and the dodo are on track or ahead of schedule, Lamm said.

Researchers are comparing the genome of the Australian thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) with that of other closely related marsupials "to figure out all the genes that need to be edited," he said.

And they are studying the stem cells of dunarts (similar to mice), the Tasmanian tiger's closest living relative, in an effort to create the many other types of cells and tissues needed to resurrect the creature, which looks more like a wolf than a feline.

The research team working on the return of the dodo is creating reference genomes of the solitaire, an extinct bird related to the dodo, and the Nicobar pigeon, which is the closest living relative to the dodo, Lamm said.

"This will allow for deeper analysis on the dodo genome," he said.

Also being studied: pigeon's primordial germ cells, which develop into sperm and egg, and the genetic modification of chickens that will serve as surrogates for the dodo, he said.

Follow Mike Snider on X and Threads: @mikesnider & mikegsnider.

What's everyone talking about? Sign up for our trending newsletter to get the latest news of the day

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Alaska schoolchildren join efforts to bring back woolly mammoths