Exclusive: In Oklahoma, hundreds of students go to court for school infractions

The schoolhouse fight began with a push from behind and a shout: "Jump him!"

Jeremy Green's son was walking down the hall at Cimarron Middle School in Edmond when he felt the push. The eighth-grader said he spun around, and a shoving match ensued between him and two other boys.

The student told them to stop, but one of them wouldn't. So Green's son ended the March 3 fight by throwing a punch, leaving a cut under the other boy's eye. Both he and the student he punched were punished with in-school suspension.

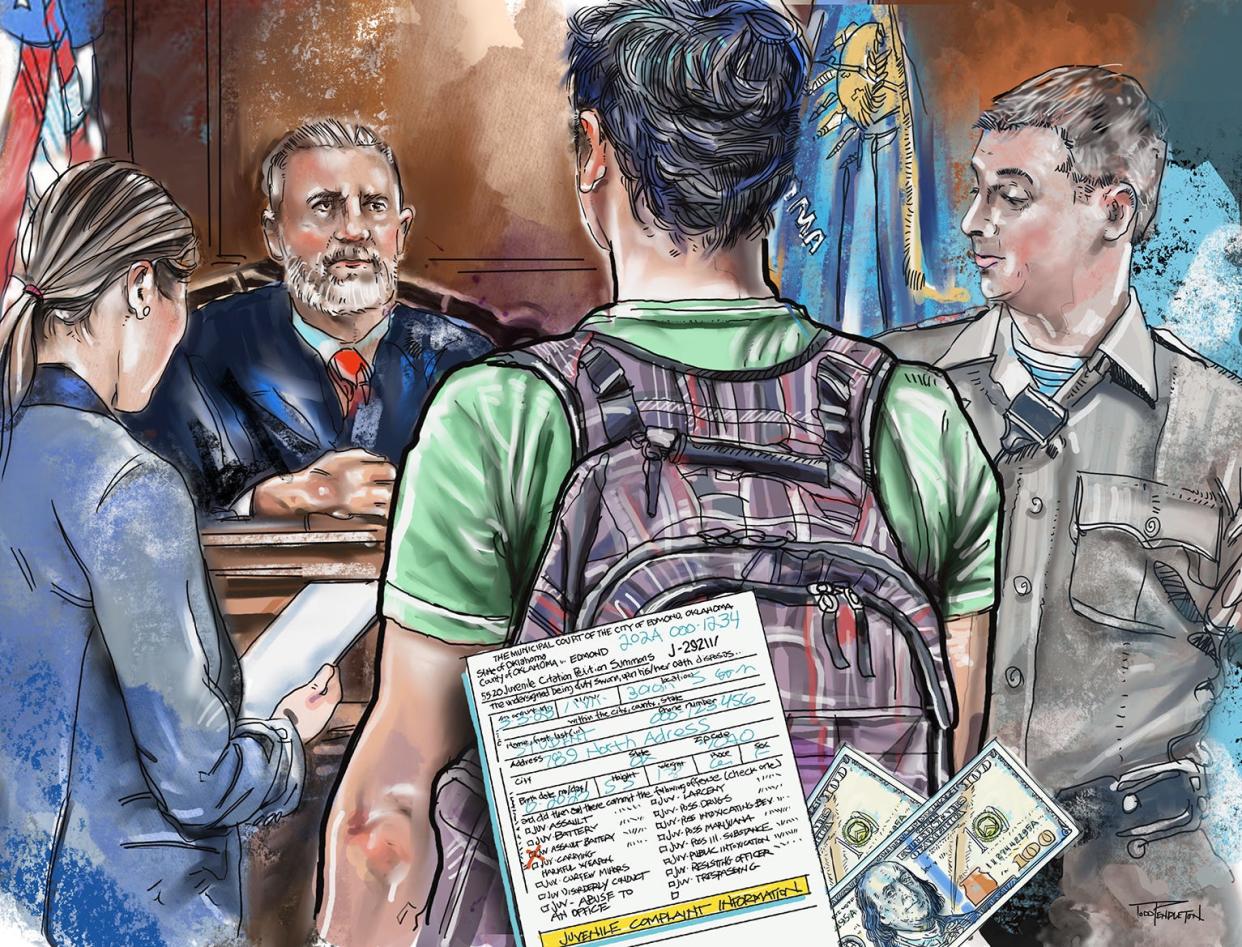

The student, whose name is not being disclosed because he is a juvenile, said he believed that would be the end of it, but the other boy's parent pursued criminal charges over the punch. After reviewing the students' written statements, a school resource officer wrote him a municipal citation for misdemeanor assault and battery.

The citation landed Green's son in front of an Edmond municipal judge, who on Aug. 1 found him guilty after a 50-minute bench trial and sentenced him to four months of probation. He was ordered to pay the full price of the citation: $820.

More: School is back in session in Oklahoma. That comes with changes, challenges, and emotions

The boy said he felt he was acting in self-defense and should have been acquitted. His family came away from the experience frustrated and stressed, Green said. To take an eighth-grader to court over a fight he didn't initiate was too punitive, Green said, especially after the school already had addressed the situation.

"He was simply trying to get someone off of him, and he feels like he can't trust the justice system anymore," Green said.

Green's son is one of hundreds of Oklahoma students ticketed at school, a common practice applied when officials decide behavioral incidents violated city laws.

In Edmond Public Schools, middle and high school students received at least 476 tickets over the past three years for a range of juvenile offenses, most commonly for disorderly conduct and marijuana possession, according to Edmond Municipal Court records.

Fining students as a method of school discipline has come under scrutiny and even been outlawed in other states, including Texas and Illinois.

Some have criticized it for criminalizing behavior that could be handled in the principal's office, initiating what many call the "school-to-prison pipeline." That concept refers to school discipline procedures bringing students into contact with the court system at a young age and enhancing their chances of future justice involvement.

"That school-to-prison pipeline is started in these very situations, and that’s where I think our biggest concern is," said Tamya Cox-Toure, executive director of the ACLU of Oklahoma.

Critics also complain the practice puts a heavier burden on poor and working-class families and disproportionately targets students of color, as The Oklahoman found with the only city that provided citation data broken down by race.

Cox-Toure says Oklahoma schools should divest from in-school police, called school resources officers (SROs), and instead hire more school counselors, nurses and social workers to address the root causes of behavior issues.

"Our opinion is just the presence of SROs definitely blurs the line between criminal activity — as you think of police officers and criminal activity — and youth behavior," she said.

More: School meals were free for 2 years, but now lunch debt is back on the table in Oklahoma

How often do police ticket students in Oklahoma schools?

No law prohibits school-based ticketing in Oklahoma. In school districts where this occurs, administrators say it's a way to respond to criminal behavior, get parents' attention and connect students with counseling services.

"If this happened the mall, or if this happened in Target, what do you think would happen?" Edmond Superintendent Angela Grunewald said. "If that happens at school, you’re going to get a citation. It’s not necessarily because it happened at school. It’s because of what happened."

In some districts, like Edmond, officers generally write tickets at the request of school administrators, city officials said, though there are exceptions as in Green's case. Other districts, like Oklahoma City Public Schools, say only police officers decide whether to give a citation.

These tickets could come with a mandatory court date, weeks of probation or community service and a fine costing hundreds of dollars or more. Juvenile citations ranged in cost from $100 to $820 in Edmond, but some students paid more if they were charged with multiple offenses.

The most frequently penalized juvenile offense in Edmond schools was disorderly conduct, a $525 ticket often incurred for fighting or using profanity. Edmond police gave 213 disorderly conduct tickets to students in grades 6-12 over the past three years.

Edmond officers issued 152 tickets for possession of marijuana, the second most of any offense in the district in that timeframe. That’s a juvenile municipal charge that costs $725 in fines and program fees.

The Oklahoman was unable to obtain citation records for one Edmond district site, Summit Middle School. That school falls under the jurisdiction of the city of Oklahoma City, which refused to provide any data on juvenile cases, citing state laws that keep these cases under seal, though the law has an exception for "statistical information and other abstract information." The Oklahoman is seeking to challenge the denial.

In Yukon, where 260 citations have been issued over three years, students as young as 12 and 13 were charged more than $800 for citations of assault and battery or marijuana possession, according to city records.

The most common citations in the district were truancy and possession of tobacco or vapor products. Officers have written tickets 85 times for each violation since 2020, records show. They come with fines of $146 and $171, respectively, but could cost hundreds of dollars more for repeat offenses.

The Yukon district treats tobacco-related cases with the “utmost seriousness” and requires students to complete an educational course if found possessing these products, said the district’s spokesperson, Kayla Agnitsch.

“In cases requiring disciplinary measures, the school collaborates closely with both the Yukon and Canadian County Police Departments,” Agnitsch said in a statement. “Moreover, all protocols and actions are consistently revised to align with the prevailing state laws.”

Truancy was the No. 1 reason for citations in Moore Public Schools. Officers gave out 68 truancy tickets to students and parents over the past three years. Disorderly conduct citations were a distant second with 20.

"Moore Public Schools knows that chronic absenteeism from school can have long-term negative consequences on the success and lives of our students," the district's spokesperson, Anna Aguilar, said. "MPS works in partnership with local authorities and allows them to enforce city ordinances and/or state law concerning truancy among our students and their families with the goal of growing an educated and strong district."

However, research hasn't shown ticketing is an effective method of improving student attendance. In South Carolina, students had poorer attendance on average after becoming involved with the juvenile justice system, according to a 2020 study by the Council of State Governments Justice Center.

What's proven to help attendance rates is to learn and address the specific reason for a student's absences, said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a national nonprofit focused on resolving chronic absenteeism.

Chang said another important method is to ensure school is a positive place where students want to be, a place where they feel engaged, connected and hopeful about the future.

“There’s nothing about ticketing kids for truancy that addresses any of that," Chang said. "If you ticket a child, it’s not a strategy for understanding why kids might miss in the first place. If tickets come with fines and one of the reasons kids are missing school are issues of poverty ... then, in fact, fining kids and their families could exacerbate some of the underlying issues that cause them to miss school in the first place.”

More: Students are back in school. What's new in Oklahoma education?

Why are Oklahoma students ticketed at school?

Grasping the scope of student ticketing in Oklahoma is a challenge. Some municipalities refused to provide records, citing juvenile confidentiality laws, that would show the number of times they prosecuted adolescents and teenagers over school-based complaints. Not all cities that reported this information included the age or race of affected students.

Ten years ago, Texas prohibited police officers from ticketing students while on their school campus, but young people in the state still can be arrested, criminally charged or referred to juvenile probation over school-based incidents.

Most of these arrests and criminal complaints are for low-level infractions, according to a report by Texas Appleseed, a public interest justice center that has researched ticketing, arrests and policing in schools. Researchers found Black, Latino and LGBTQ+ students were disproportionally impacted.

These disparities are evident in Yukon, the only municipality to provide The Oklahoman with citation records broken down by gender and race.

Black students received 14% of the tickets issued in Yukon Public Schools, despite making up 4.5% of the district's student population. They also received the highest average fines, $473 at the district's middle school and $346 at Yukon High School. White students paid 16% less on average at the middle school and almost 20% less at the high school, an Oklahoman analysis found.

Yukon officials did not respond to a question about the disparities.

After more than a decade of research, Texas Appleseed has yet to find any empirical or anectdotal evidence showing citations improve academic results, limit truancy and reduce disciplinary referrals, said Andrew Hairston, director of the center's Education Justice Project.

"It further pushes children out, further makes them feel isolated from their peers (and) from the school environments at large, and ultimately can set them on a course where young people might end up in the criminal legal system in their teenage years or in their 20s and 30s," Hairston said.

Grading Oklahoma: A visual look at education in our state

Multiple Oklahoma school districts said they don't keep citation records, and their procedures regulating police involvement with students differ by school district, sometimes even by school.

The Oklahoman contacted the 10 largest brick-and-mortar school districts in the state, which represent 215,000 of Oklahoma's 701,000 students in public schools. Eight of those districts confirmed students are ticketed in their schools when behaviors are deemed a violation of local laws.

The Oklahoman did not include the state's third-largest district, Epic Charter School, in the survey because its education is primarily virtual.

Ticketing is often treated as a “last tool” in Broken Arrow Public Schools, the sixth-largest district in the state, said Derek Blackburn, executive director of student services. But if a fight is particularly violent, the students involved could be ticketed even on their first offense.

Blackburn said citations have become more necessary because parents and students no longer view suspensions with the same gravity.

“That citation piece is trying to get the attention of parents, saying this behavior is not acceptable and we need your help,” Blackburn said.

The city of Broken Arrow declined to provide any records tallying the number of juvenile citations in Broken Arrow schools, contending the information is confidential.

In Oklahoma City, where the municipal court also refused to turn over these records, school district officials say a citation leads to required counseling classes, which otherwise wouldn't be mandatory.

“There’s a host of services that come through the city of Oklahoma City that come through probation, including drug testing, therapy and counseling," said Wayland Cubit, the Oklahoma City district's director of security and a retired police lieutenant. “Literally, the citation is the on-ramp to those youth services that you want to get to a kid.”

These resources should be provided without penalizing a student in court and enforcing burdensome fines, said Hairston, of Texas Appleseed. Instead of punitive measures, Hairston encouraged schools instead to consider restorative discipline practices that respond to misbehavior with peer mediation and promote building a community within the classroom.

Lawton and Tulsa Public Schools were the only school districts of the 10 largest in the state that said they explicitly don’t condone ticketing on their campuses.

Lawton aims for a purely educational environment within its schools and prefers students view campus police officers as a layer of protection, not an arm of discipline, said Jason James, chief operations officer.

The district's campus police force is told to patrol outside school buildings to focus on guarding against external threats, James said. In instances of drug or weapon possession, officers will enter a Lawton school, collect evidence and write a police report, not a ticket. City or county prosecutors then decide whether to take the matter to court.

"Sometimes our teachers think that when there’s two kids that get into a fight that that’s a criminal act that needs to be handled by police," James said. "We just don’t see it that way. We think that’s a behavior issue that our administrators can handle."

Tulsa Public Schools outlined its potential discipline in a behavioral response plan. Court referrals and citations aren't on it.

That's because the school district believes in a more comprehensive approach, said Jorge Robles, Tulsa's chief finance and operations officer.

"Ticketing might be focused on the symptom, and you’re not really focused on what’s behind that (behavior)," Robles said. "It’s more of a reaction that loses power over time."

What happens after a student receives a ticket?

Edmond students who receive a ticket first meet with a compliance officer at the municipal court. In that initial interview, families usually decide whether to go to trial or take a plea deal and enter straight into juvenile probation.

The probation process is meant to be rehabilitative, said Yolanda Whitlow, the city's municipal court administrator. Students are required to complete community service and take a course that relates to their offense, often for anger management, counseling or substance abuse education.

"Our main goal is to help you. Sometimes the offense, it’s just a cry for help," Whitlow said. "If we can help that child to turn around, that’s what we focus on."

Unlike for adults, these classes are mandatory for juveniles on probation in Edmond, and the $240 cost to take these courses is added to students' citation fees.

Edmond's municipal judge, Diane Slayton, said the court covers probation costs for juveniles whose families are in financial hardship.

"The fines and costs are the absolute least of my concern, but I do always tell a kid that getting in trouble costs money," Slayton said. "What fines and costs we have now would be nothing really compared to what they may be facing when they turn 18 with this kind of behavior."

Green, whose son was ticketed in Edmond, said the juvenile court experience has been the opposite of restorative. Instead, he said it's been a financial burden — not only the $820 fine, but the hours of work he missed to deal with the situation.

His son will have to complete four months of probation and 50 hours of community service, along with paying the fine.

"They claim to do this to help the child," Green said. "They say it’s not harmful in any way. It is very harmful. You’re treated like you’re guilty right away without any chance to prove your innocence."

Green said testimony and evidence at his son's municipal trial focused solely on the punch the boy threw. He said he was cut off any time he tried to establish what happened before or after the act. He had considered hiring an attorney, but a law firm he contacted told him to save his money, there wasn't much they could do, Green said.

Among the only pieces of evidence was a statement his son wrote the day of the incident in which he reported punching the other boy in self-defense, he said. The eighth-grader told The Oklahoman he thought this should have acquitted him, but instead he said he learned telling the truth "doesn’t help in this situation."

"I’ve never been to court," he said, "but after this incident, I don’t trust it at all."

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Police ticket hundreds of Oklahoma students for school infractions