A New Exhibition in Philadelphia Examines the Hidden Histories of Reproduction

When I returned to work after having my first child, I had 20 minutes between patients to pump milk. Accessing the designated pumping rooms, however, required a 10-minute walk and waiting in line; so I pumped in my exam room instead, between wound dressings, STD checks, and tearful conversations about new HIV diagnoses. It took time to meticulously disinfect the space before and after. I weighed the etiquette of storing human milk near my coworkers’ lunches (opting instead to lug a cooler in each day). I tracked the output: A suboptimal session from stress, dehydration, or malfunctioning pump parts could compromise nursing. And another several minutes were spent cleaning those numerous parts and their tubing. If something was broken or lost, it would mean hand-pumping, excruciating pain, and sometimes mastitis. The math did not work out. I fell behind schedule, finishing clinic notes after work hours, usually while nursing my infant.

It was an isolating, miserable part of my life juxtaposed with the joy of having a new child. My head spun navigating the daily logistics of motherhood and work responsibilities. As a physician, I regularly discussed sickness, death, and sex with my patients while decrying stigma. But I defaulted to treating my own bodily experiences as impolite and furtive. I had enormous privileges —maternity leave, childcare, a supportive partner and colleagues—and still I was drowning. I did not have words at that time for the bewilderment of getting through each day.

Since meeting at a baby shower in 2017, the design historians Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick have tried to elevate the narratives and history around fertility, childbirth, parenting, menstruation, and similar experiences through the lens of design. In 2015, Fisher had been a curatorial assistant at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where she proposed adding a midcentury breast pump to the collection. (The device had significantly improved on the discomfort and noise from the previous adapted dairy farm equipment.) She argued that this breast pump model, like celebrated household appliances and other “humble masterpieces,” had advanced a design that meaningfully bettered the lives of women. This was worth canonizing, she said. Yet the museum politely disagreed.

“These designs often live in very embedded ways in our memories and our bodies,” Fisher and Winick write in a new book, Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. “We don’t just remember our first period, but also the technologies that first collected that blood. We don’t just remember the way babies arrive, but also what they were wrapped in when they finally reached our arms.”

Home Pregnancy Test Prototype

Fisher and Winick’s “Designing Motherhood” project ushers those experiences and tools into design history. “We were rubbing our hands with glee in 2017,” recalls Fisher, who had thought publishers and museums would be eager to rectify the oversight. “We were very naive. Literally no one wrote back.” Yet four years later, their proposal became the “Designing Motherhood” exhibit at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, which considers a broad spectrum of reproductive stages and needs among diverse people. Closely examined objects and ideas include the menstrual cup, speculum, sterilization abuse, baby showers, Kegel exercises, and the experience of masculine birth as a transgender birthing person. The initial difficulty in finding a platform for these narratives is also part of the project, as is the prodigious effort to connect to the collaborators who eventually helped shape it.

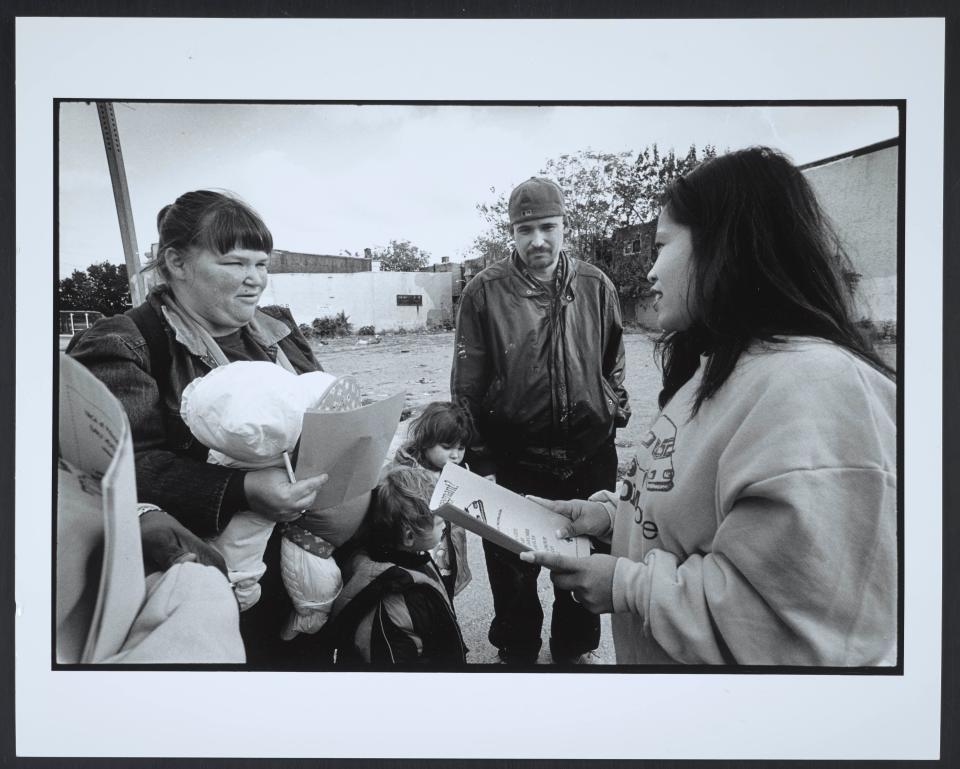

One key partner was the Philadelphia-based Maternity Care Coalition (MCC). For 40 years, MCC has served the maternal and early childhood needs of underserved communities in southeastern Pennsylvania. The group provides health services, home visits, education on childbirth and infant care, and lactation support, and they were early champions of community-based doulas. Zoë Greggs, a curatorial assistant and artist, worked with Fisher and Winick to link the design world with the service and advocacy work of MCC, as well as to curate the overall project. “The ideas were super radical and refreshing in the spaces in which we worked,” she says.

Tekara Gainey, an MCC community adviser and full-spectrum doula trained in public health and anthropology, was initially uncertain about the partnership. “How are we using design and what does that mean and how does that relate to the work we are doing in reproductive justice?” she wondered. Yet over the course of her collaboration with Fisher, Winick, and Greggs, she found that “They get it!... Narrators [with platforms] are often white or white-passing people telling other people’s stories,” whereas this project “is highlighting the voices of those who are actually doing the work,” and centering the experiences of people not often represented at the gates of high-culture institutions.

“Why have the designs we explore in this book remained so hidden even as they define the everyday experiences of so many?” write Fisher and Winick of the project’s genesis. “One answer is that most heads of publishing houses, museum directors, chairs of exhibition proposal committees, and chief curators we encountered have not, and never will, directly use these things.… Philadelphia-based [artist] Aimee Gilmore recounted the time in graduate school that her professor, glancing at her desk during a studio visit, mistook her breast pump for an air horn.”

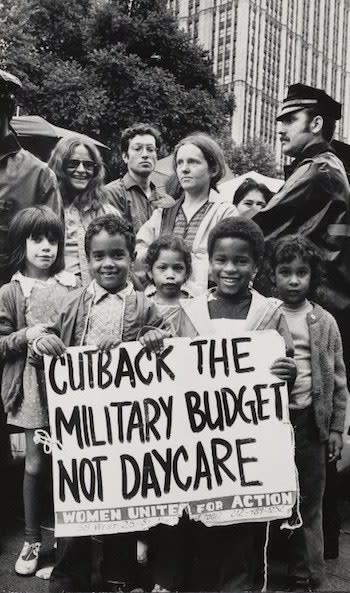

One of the essential revelations of design history is how the culture and policy surrounding any given object are part of the design experience. MIT hosted a “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” hackathon in 2014, wherein designers and engineers joined providers, parents, and babies over a weekend to try to improve the experience of breastfeeding. It quickly became apparent that the effort meant more than optimizing device ergonomics—the time and space to pump was shaped by public policy and workplace structure, and varied significantly across socioeconomic groups. “Designing Motherhood” ostensibly opens in an era of frank conversations about femme bodies, pleasure, and the full spectrum of fertility. Still, those conversations are often driven by people selling something—the orgasm industrial complex; fertility “femtech” concierge health services with intrusive data collection; or the wellness industry, which leverages the genuine failures of medicine to serve women’s pseudoscience. These voices cater to a well-off, paying customer, while “Designing Motherhood” explores not only consumer technology, but also equitable access and the infrastructure of care.

The Affordable Care Act required that employers of a certain size provide designated lactation space, but less than half of women have access to them. A discussion of a breast pump device is incomplete without factoring in adequate maternity leave, which improves public health outcomes for both mothers and babies, and could decrease the need for pumping in the critical stages of early infancy. Without paid family leave, a quarter of new mothers return to work within 10 days of birthing a baby; almost half return in fewer than 40 days. When MIT hosted its second hackathon in 2018, it explicitly acknowledged the “systems, programs, and culture” that shape the experience of breastfeeding, organizing a policy summit on family leave and focusing on the often-overlooked needs of low-income women.

This intimate weave of policy as design was familiar to Gabriella Nelson, associate director of policy at MCC and a city planner. In her view, accurately grasping the interconnectedness of fertility, reproductive justice, and motherhood requires nothing short of this expansive framework. “We advocate for a wide range of things, but that’s what motherhood is,” she says in Fisher and Winick’s book. “Motherhood is housing, it is food security, it’s public education, it’s health care systems, it’s public transportation.”

The centrality of policy in shaping our lives has been especially glaring during the COVID-19 pandemic. My return to work in April 2020, after my second child was born, was to a radically changed world: Breast pump ergonomics had improved, but more significantly, the pandemic had disproportionately destabilized women’s work lives. While women make up half of the workforce in general, they are 64% of all frontline workers and 76% of health care workers—and tend to be the hardest hit by job losses and childcare closures.

That a public health crisis would disproportionately impact mothers is not news; we have also seen this in the opioid epidemic and mass incarceration. A highly contagious infection has made it clear how inextricably connected we are—but this has always been true. For much too long, the work of organizations like the MCC has been “siloed as a ‘women’s issue,’” Fisher and Winick write, “rather than understood as the foundation of healthy citizens, societies, and culture at large.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue