Exile group planning overthrow of Venezuelan government tried to hire Trump-connected lobbyists

Working from an office near the Miami airport, three Venezuelan exiles are plotting the overthrow of the government of President Nicolas Maduro, claiming they have military forces standing by in five countries, including the United States. And they say they’re making inroads with the Trump administration, which has expressed support for regime change in the country.

Last March, the exiles created a Miami-registered nonprofit called Venezuela Freedom Inc., which was soon rechristened with the less business-minded moniker of Venezuela Freedom Foundation. The website includes a nine-slide “Strategic Plan” from May 2018. The first slide after the cover page is entitled, “Venezuela Needs a Regime Change.”

The three men see themselves as part of a government in exile and are putting together a list of post-coup Cabinet ministers. They plan to move back to their homeland as soon as “the invaders are thrown out,” Jean Pierre Chovet, a businessman and one of the three leaders, said in a phone interview. He said action is needed swiftly as an assortment of narco-traffickers and terrorist groups, including the Islamic State, have established five government-approved training camps in Venezuela, including one on Margarita Island, a popular tourist destination.

Chovet’s two business partners are Julio Rodriguez Salas, a former Army colonel, and Carlos Molina Tamayo, an ex-Navy vice admiral. The pair were both key players in a botched, deeply unpopular 2002 coup attempt against Hugo Chavez, Maduro’s predecessor. (Rodriguez and Molina did not reply to requests for comment sent through Chovet.)

The Venezuela Freedom Foundation says it is sending humanitarian aid to Venezuela, but its plans include “a piece of military action” that will topple Maduro, Chovet said. It will be led, he said, by “clean” anti-Maduro army personnel in Venezuela, along with military forces said to be mustered in the United States, Colombia, Peru, Brazil and from a Caribbean island Chovet said was best not to identify. He said the foundation had support from the governments of Colombia and from officials close to Jair Bolsonaro, the incoming right-wing president of Brazil.

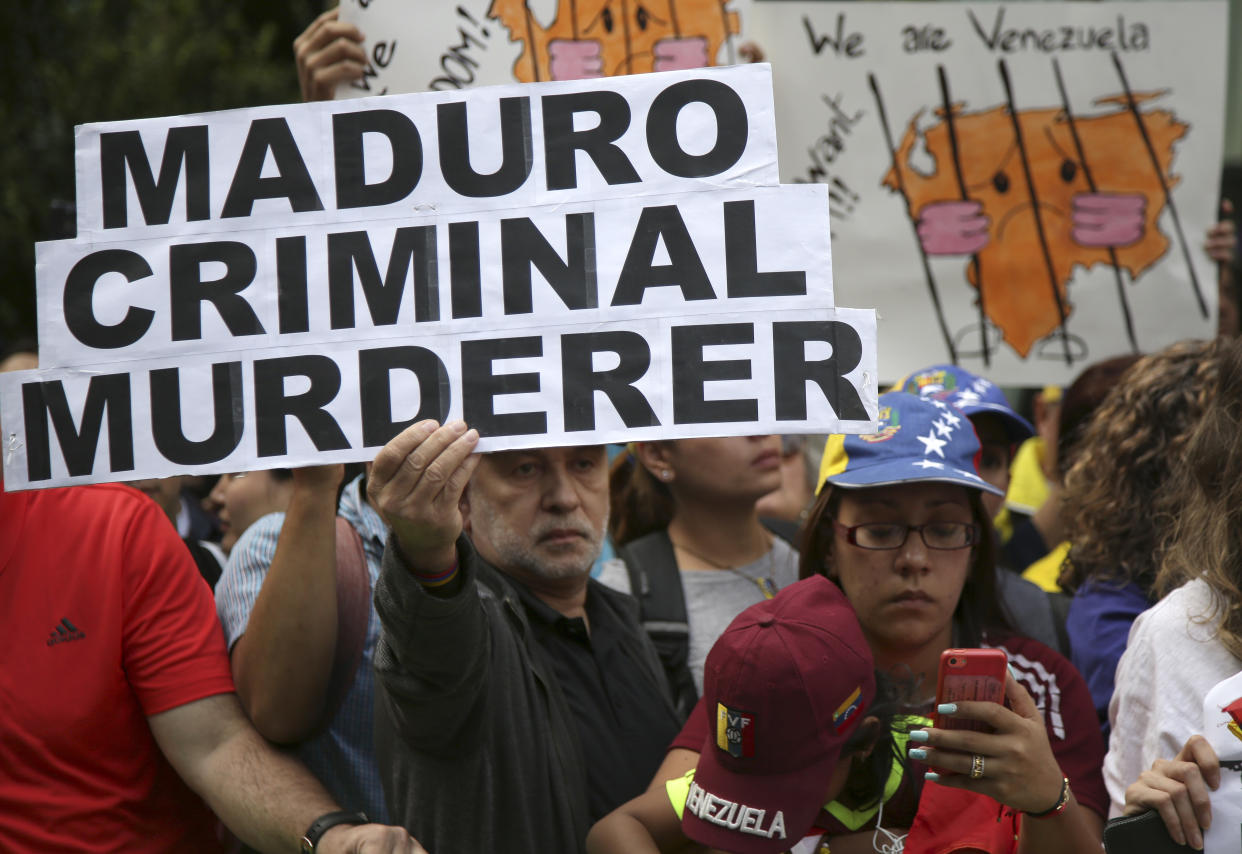

Now, they hope — with some help from the Trump administration — the second time’s a charm. “We don’t believe in dialogue,” he said. “The regime are assassins.”

The Venezuela Freedom Foundation’s work — from within the borders of the United States — to launch an armed overthrow of a foreign government raises a fundamental question. While the Trump administration has been openly calling for regime change in Venezuela, which would seem to encourage or at least embolden groups like the Venezuela Freedom Foundation, it’s highly likely to be a crime for private American citizens to actually get involved in Maduro’s forcible overthrow.

And that’s precisely what the foundation has sought to do. In an effort to curry favor with the Trump administration, the trio of exiles sought to retain as a lobbyist Otto Reich, a U.S. ambassador to Venezuela under Ronald Reagan and a senior official in the George W. Bush administration who supported a failed 2002 coup in the country. They’ve also publicly claimed — falsely, it turns out — to have retained a prominent lobbying firm headed by a close friend of President Trump’s.

No matter what the position of the Trump administration, it’s illegal for private U.S. citizens to seek the forcible toppling of a foreign government, according to Brett Kappel, a prominent Washington attorney and expert on foreign lobbying. “If they had successfully enlisted Americans to support violently overthrowing the Venezuelan government, those Americans would be facing serious criminal jeopardy for violating the Neutrality Act,” Kappel said. Normally, not registering as a foreign lobbyist while carrying out such work would be a crime. But if anyone registered to advocate for a violent regime change operation, they would have been simultaneously confessing to a felony, Kappel added.

Nicolas Maduro, a former labor leader and vice president of Venezuela, took over when Hugo Chavez, a longtime bête noire of official Washington, died of cancer in 2013. Maduro won a special election that same year by less than 1 percent and was reelected in a landslide in May of this year. The election was boycotted by most of the opposition, and the United States and many other governments refused to recognize the results.

President Trump has long made clear he favors regime change in Venezuela, which has been suffering record-setting hyperinflation along with critical shortages of food and medicine. (The Venezuelan government has said sanctions have greatly contributed to the country’s economic problems.) Starting last fall, the Trump administration “held secret meetings with rebellious military officers from Venezuela to discuss their plans to overthrow President Maduro,” the New York Times reported earlier this year.

But the administration is now openly calling for Maduro’s ouster. “For the safety and the security of all people in Latin America, it is time for Maduro to go,” Nikki Haley, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, said earlier this year during the Washington Conference on the Americas. Trump made similar comments in late summer, including, “Venezuela is a mess. The place needs to be cleaned up.”

Early this month, U.S. national security adviser John Bolton spoke at Freedom Tower, a building where anti-Castro Cubans were welcomed in 1960 after Castro’s revolution toppled dictator Fulgencio Batista. “The troika of tyranny in this hemisphere — Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua — has finally met its match,” he declared. He referred to the leaders of that trio of countries as “clowns” who were “akin to Larry, Curly and Moe” of the Three Stooges.

Yet the trio of exiles who want to topple Maduro may have a greater claim to that name. Even before incorporating the foundation, they appeared last year at a number of public events in Florida, home to an estimated 140,000 Venezuelan exiles and Venezuelan-Americans. They were anything but subtle about their plans.

During a February 2018 event in Tampa, Molina Tamayo said that the only means to “rescue” Venezuela was to “intervene in the country, detain the delinquents, put in place a transitional government and within a prudent period of time call legitimate elections,” according to a Spanish-language account in the Orlando Sentinel. He claimed Maduro was negotiating to give Russia and China military bases in Venezuela and that the country was being “hijacked” by Iran, Colombian drug cartels and “Palestinian Hezbollah.” (Hezbollah is a Lebanese organization.)

The opposition in Venezuela was divided about whether to participate in last May’s presidential election, but the trio opposed it. “We don’t believe in negotiations,” Chovet told the audience. Another local account said the exiles called for “international humanitarian intervention, even if that intervention has to be armed,” which the trio believed would be necessary.

They incorporated the Venezuela Freedom Foundation last spring with Rodriguez as the president and registered agent, while Chovet and Molina Tamayo share the title of vice president. “The corporation will serve as a Florida nonprofit organization focusing on humanitarian and political issues and providing advisory services for the rescue of the Venezuelan people,” read the registration papers.

Three prominent Republicans with direct knowledge of the trio’s activities, and Reich’s relationship with them, viewed the exiles as self-promoting opportunists and dangerous zealots. “They were anti-government bomb throwers,” one said. “They talked about sending humanitarian aid, but the main plan was for the army to take over. They bragged they could have 1,000 people on the ground to run the new government a day after Maduro was ousted.”

The three Republicans loathe Maduro, but they wanted nothing to do with a plan for regime change. “They were the gang that couldn’t coup straight,” said another of the Republicans, who have all long been active in national party politics. “I agree with them about getting rid of Maduro, but not with their approach. There are laws about that.”

The three men talked up plans to create a group called Mothers to the Rescue, whose ostensible purpose was to send humanitarian aid to Venezuela. But the three GOP sources familiar with their plans told me that the charity was nothing more than an afterthought and effectively a facade. The trio never created the organization and while they reserved a website for it with GoDaddy.com, it never launched.

Rodriguez, the head of the foundation, does have coup experience, though not a successful one. In April 2002, he was among a junta of military officers and right-wing leaders that briefly ousted President Chavez in a coup and installed in his place Pedro Carmona, director of Venezuela’s equivalent of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Molina Tamayo, one of the foundation’s vice presidents, also has a coup attempt on his CV. A former Venezuelan Navy admiral who has spent much of the last two decades in Spain, he publicly denounced Chavez as “unpatriotic” two months before the coup and called on him to resign. The Chicago Tribune reported that he was one of key military officers “building support … in the armed forces” for the coup. Carmona, Molina Tamayo and another military officer were the first three members of the post-coup government.

After proclaiming democracy, Carmona quickly dissolved the legislature and Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution. (Then-Col. Rodriguez appeared on national TV soon after it was underway and told viewers he and other military officials had been planning the operation for many months.) However, Chavez was immensely popular at the time. The streets of Caracas exploded in protest, and within a few days the Carmona government collapsed and Chavez was back in power.

Turning to Reich — a right-wing Cuban-American and longtime leader of Miami’s anti-Castro movement — for support would have been a no-brainer. Reich has strong ties with the Trump administration, which has appointed a number of his colleagues in the anti-Castro movement to top Latin America policy positions. And he also has a history of supporting coups in Venezuela. On the day Carmona took power, Reich, who was then an assistant secretary of state, met ambassadors from Latin America and the Caribbean in his office and endorsed Chavez’s removal from office.

Reich now heads a Washington PR and advocacy firm and has a consulting relationship with Ballard Partners — headed by Brian Ballard, a close friend of the president’s and described by Politico as the “most powerful lobbyist in Trump’s Washington” — which the exiles hoped to retain as part of the deal.

Ballard once represented Trump in Florida and was a state finance chairman for his presidential campaign and a vice chairman for his inaugural committee. For the Venezuela project, Reich partnered with Sylvester Lukis, a Ballard managing partner who moved to Washington after the 2016 election to open the D.C. office.

The foundation’s “Strategic Plan” claimed that it worked closely with “the lobbying firms of Ballard Partners and Otto Reich and Associates” to interface with the Trump administration. (The plan was taken off the site less than a day after this writer inquired about it.) Chovet says the group had inked the deal with Reich after a series of discussions that began last March. “Otto is not working for us at the moment, but he introduced us to the right people in Washington,” Chovet said. “He did a good job for us.”

In private, the exiles were even more aggressive. At least through March they were boasting to two of the Republican sources that Reich was touting them in GOP political circles and would be lining up congressional and Trump administration support for Maduro’s overthrow. “Otto is a fervent anti-Communist, and these guys passed muster with him,” one of the sources said. “All they cared about was getting American support to overthrow Maduro, by any method.”

A second GOP source said the trio made similar claims to him. “I sympathized, people in Venezuela are suffering and I don’t like Maduro,” this person recalled. “But all they wanted was inside baseball to bring about Maduro’s overthrow.”

Reich confirmed that he had multiple conversations and meetings with the trio of exiles, but disputed significant components of Chovet’s account. He denied that he ever closed a commercial deal with the Venezuela Freedom Foundation or received any compensation from it. He said he had written a proposal for the group — which he described as “strictly humanitarian” — and that he may have signed “some piece of paper” about a potential lobbying arrangement, but nothing ever came of it and “no money changed hands.”

In a phone conversation, Reich said he met Rodriguez roughly four or five years ago at a public event, and that a mutual colleague, whom he declined to identify, put them back in touch earlier this year. “I guess he didn’t know how to get in touch with me,” he said.

Reich described Rodriguez as a friend. “I have had numerous conversations with Julio,” he said. “I have other reasons to talk to Julio beyond Venezuela Freedom.”

He said that Rodriguez and he had a one-on-one meeting to discuss a potential business deal involving advocacy against the Maduro government. That was followed by a meeting with the former colonel, Chovet, Molina and several other people, whose names had escaped him since.

After that, Reich arranged a conference call between the three men and “about half a dozen Washington entities.” Lukis of Ballard Partners participated in the conversation, he remembered. “I have a consulting relationship with Ballard,” he said. “They have right of first refusal. They [the trio] wanted Ballard involved, and I said, ‘I’ll see what they say.’”

Ballard flatly denied that his firm had worked for the exiles. “I’ve never even met these guys,” he wrote in an email. He confirmed that Reich and Lukis had met with the trio and raised the opportunity of representing them.

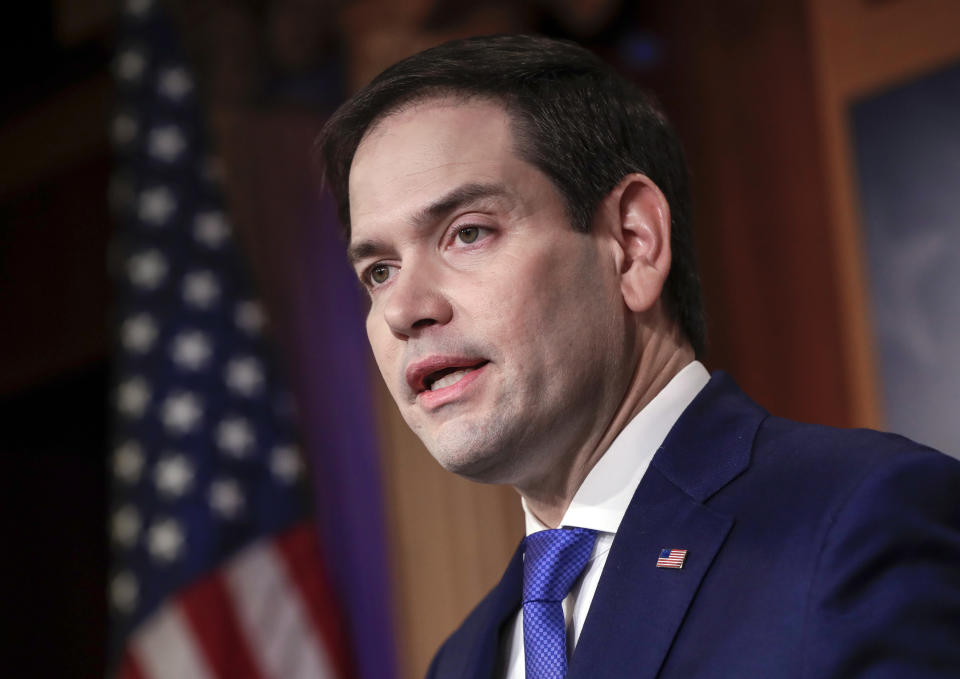

But Reich said negotiations foundered, in part because the exiles had too lofty expectations. “I don’t want to disparage them but they wanted to do some things I knew we couldn’t do,” he said. “I had sort of an agreement with Julio, but he couldn’t get the agreement of the others. I never did any work for them and I never contacted anyone on their behalf, including Sen. Rubio.”

Reich said that in his discussions with the trio, he was acting as a representative of his firm, Otto Reich Associates LLC, not Ballard Partners.

Chovet declined to comment further after being informed that Ballard and Reich had disputed his version of events and had denied ever taking money from the trio or its foundation. “There is information classified as P&C [Private & Confidential] so we need to sign an NDA [non-disclosure agreement] before we continue our conversation,” he wrote in a text message.

No work contract exists between Reich and the trio, the lobbyist insists. “We talked several times, but we never reached an agreement,” Reich said. “I asked certain questions and never got satisfactory answers and moved on. I’m a U.S. citizen and I have to abide by U.S. laws. There are laws about the use of military force. I know where the lines are drawn and certain alarm bells went off.”

It would be easy to dismiss the Venezuela Freedom Foundation as a hobby for buffoonish, wannabe coup leaders, but the group appears to be well funded. One of the Republican sources said the trio claimed to have millions of dollars available for its 2018 budget. One of their top donors, he said, was a Venezuelan construction executive, whom he described as “a Gucci loafer type.” The executive was an “integral part of the fundraising mechanism for these guys,” the source said.

Chovet had declined to discuss where his group’s money was coming from other than to say it was provided by private individuals in the United States and Europe. It’s clear, though, that the trio had access to substantial funding. Chovet said their group had two offices in the Miami area as well as a small office in Houston, headquarters of Citgo, an energy firm majority-owned by Venezuela’s state-owned PDVSA oil company.

The foundation had a financial committee that raised cash, Chovet said, but it was “never enough.” However, the trio had been “assured there will be more money” as progress toward overthrowing Maduro is made.

It’s not clear how much, if any, support the Trump administration is offering the exiles, and some potential allies have shunned them because of their extremist positions. Chovet stated that his group has allies in Congress, including Sen. Rubio of Florida, who has expressed tacit support for removing Maduro by force, and within the Trump administration. “We have had special discussions with the Department of Defense,” Chovet said. “I’m not the one dealing with them directly, that’s my partners in Venezuela Freedom.”

The White House and Rubio’s office did not reply to requests for comment.

Putting aside the question of legality, even many critics of Maduro think a military overthrow is a bad idea, especially if it involves troops or direct support from the Trump administration.

“Maduro is not a good ruler, but he hasn’t done anything to threaten the United States and there are no U.S. national security interests that require regime change,” said Robert Moore, a public policy adviser for Defense Priorities and former national security and defense staffer for GOP Sens. Mike Lee and Jim DeMint. “Any issues between our two countries can be better mitigated by statesmanship and negotiations. There’s no way I can see how a regime change operation will improve things for Venezuelans, and it means more time, treasure and blood for the United States.”

Andrew Bacevich, professor of history and international relations at Boston University, was equally dubious. “We know how to topple regimes, but we don’t know how to establish a stable political order afterwards, and our experiences over the last two decades or so have affirmed that time and again,” he said. “I see no reason to think that overthrowing the government of Venezuela will be any more successful than what happened in Afghanistan, Libya and Iraq.

“For any advocate of regime change in Venezuela, the operative question is, ‘What’s next?’ If they don’t have a good answer, it’s an invitation to folly.”

For the foundation’s leaders, what’s next would be high-level roles for themselves. They all planned to get top positions in the post-Maduro government they were hoping to install, one of the sources told me. Rodriguez and Molina dreamed of bagging high-level military positions, while Chovet was shooting for a slot in the oil ministry or at PDVSA, the state oil company, the source said.

However, It’s not apparent how much support the exiles have inside Venezuela for their grand plans. Chovet said the foundation is working closely with select opposition groups in the country and with the self-declared Supreme Court in Exile, which operates out of Panama. However, he complained that some politicians had “betrayed” the trio by promising to align with them but separately negotiating with the Maduro government. “We lost a lot of time and money,” he lamented.

Nonetheless, Chovet and his colleagues are optimistic and gearing up for a new push to depose Maduro now that the U.S. midterm elections are over, he said. They’re hoping for an invasion early next year.

“We’re putting together a broader alliance before we go back to Washington, that’s what the Trump administration is waiting for,” he said. “Everything has been on standby because of last Tuesday’s election, but we have all the pieces in place so now it will be easier to get things started.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

The CIA’s communications suffered a catastrophic compromise. It started in Iran.

Ending the Qatar blockade might be the price Saudi Arabia pays for Khashoggi’s murder

How Robert Mercer’s hedge fund profits from Trump’s hard-line immigration stance

Trump’s target audience for migrant caravan scare tactics: Women