Exotic horses – used in jousting tournaments – found buried near Buckingham Palace

Members of the elite class in medieval England were not known for their modesty and pragmatism.

They wanted the best of the best, and this mentality extended to their horses.

“The significance of horses to life in medieval England cannot be understated,” researchers said in a March 22 study published in the journal Science Advances. “Procuring high-quality horses for labor, war, travel, and tournaments was of paramount importance.”

The researchers said kings, among other high-ranking elites, used lots of resources to make sure the best horses in the world were brought to England, but very little is known about where they came from — and how they got there.

Then a horse cemetery was unearthed.

‘Elite equestrians’

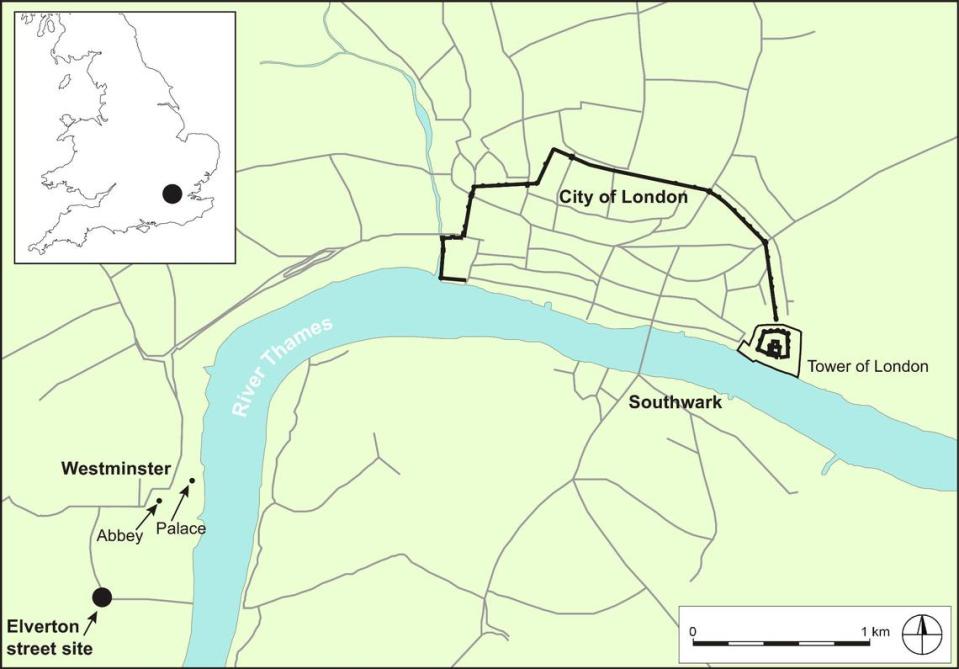

On Elverton Street, in the neighborhood of Westminster, just streets away from Buckingham Palace and Westminster Abbey, a housing redevelopment project began in the mid-1990’s, the researchers said.

Uncover more archaeological finds

What are we learning about the past? Here are three of our most eye-catching archaeology stories from the past week.

→ Hidden tunnel network found at abandoned 800-year-old home in France

→Metal detectorist stumbles on 650-year-old artifact — and sparks a mystery

→ Ancient Roman ruins found in Germany help solve 140-year-old mystery, photos show

When they dug into the ground, archaeologists discovered 197 pits, 56 of which were filled with the remains of animals, according to the study.

More than 70 horses were found to be buried here, the researchers said, and the site was dated to between 1425 and 1517, the late medieval and early Tudor period.

The horse remains sat for decades, as more information was limited by the technology available for the researchers, but some conclusions could be made from their bones alone.

“These animals are big and physically robust,” study author Oliver Creighton, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, said in a news release.

The horses had fused vertebrae, which was typical of horses that carried heavy loads or often had people on their backs, according to the study.

“Westminster Palace was also a noted and busy royal tournament venue, where jousts were regularly held, while the pasture that adjoined the Elverton Street site was the venue of other tournaments and combats,” the researchers said.

One horse also had evidence of a bit that was commonly used by “highly trained elite horses from the 14th century onward,” according to the study.

This, combined with the location, “really points to them being jousting horses,” Creighton said. “There’s a vast amount of prestige involved.”

Where did they come from?

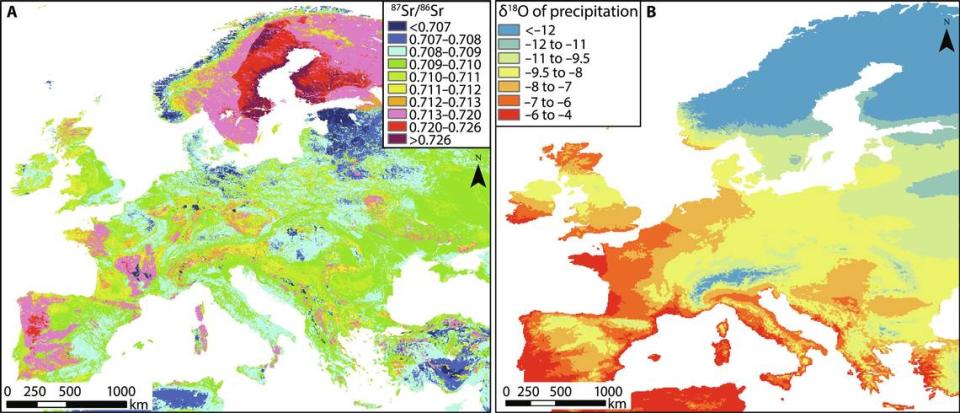

Using the enamel from the horses’ teeth, the researchers were able to identify the chemical signatures from the water they drank during their life, proving that the horses were not English-born, according to the study.

The researcher analyzed the teeth for strontium isotopes, an element that builds up in tooth enamel in the early layers of teeth as the horse ages, according to the release.

The isotopic signatures look different depending on where the horse spent its first few years of life, the researchers said, and it can be used to tell where they were likely born.

“Fifty percent of the horses we looked at came from a long way off,” study author Alexander Pryor, an archaeological scientist at the University of Exeter, told Science.

A few horses had isotopes belonging to the British chalklands across southeast Britain, the researchers said, which includes 14th-century London.

Others came from further away in the United Kingdom, including Dartmoor and southwest Britain, the researchers said.

Nearly half of the horse remains that were tested came from Scandinavia and mainland Europe, including Sweden, Finland, the Danish island of Bornholm, and locations throughout the central and southern Alps, according to the study.

Horses regularly were bred and traded internationally during this era, the researchers said, including from royal efforts to diversify the equine stock.

The proximity of the horse cemetery to a thoroughfare between Lambeth and Westminster suggests the horses were headed to the Westminster complex, the researchers said.

These horses were fully buried, and not just in pieces, which was odd for the time period, according to the study, were imported from abroad and were near the center of British power.

“While none of these features are necessarily unique to high-status horses, in combination, they suggest strongly that the Elverton horses are elite animals owned by elite households, including possibly the royal household itself,” the researchers said.

Roman helmet looked like a ‘rusty bucket’ when it was found in UK. Now, it’s restored

Ancient warehouse — from first Roman city outside Italy — discovered in France. See it

Mysterious wooden train car — almost 100 years old — unearthed in Belgium, photos show

137-year old shipwreck, doomed by sudden fog, found ‘remarkably intact’ in Michigan