Expanding history: Event on maroons, marronage of the Lowcountry aims to start conversation

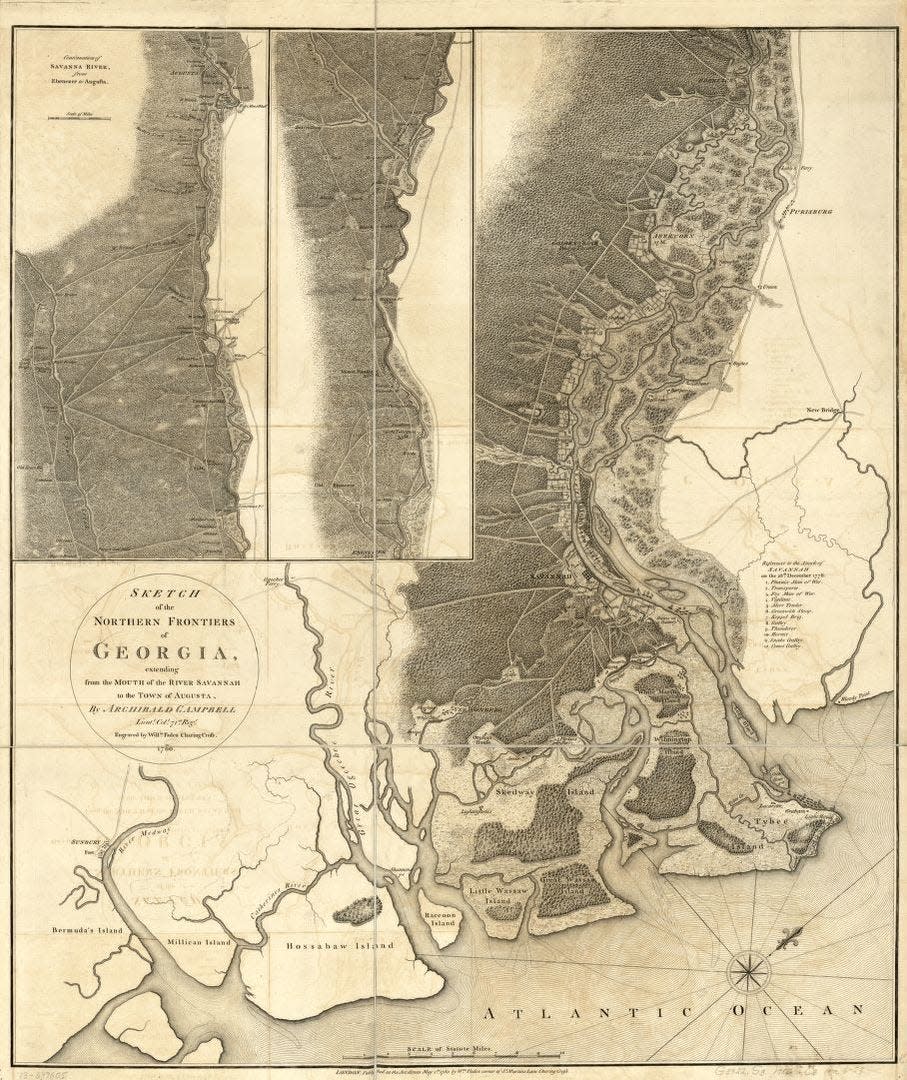

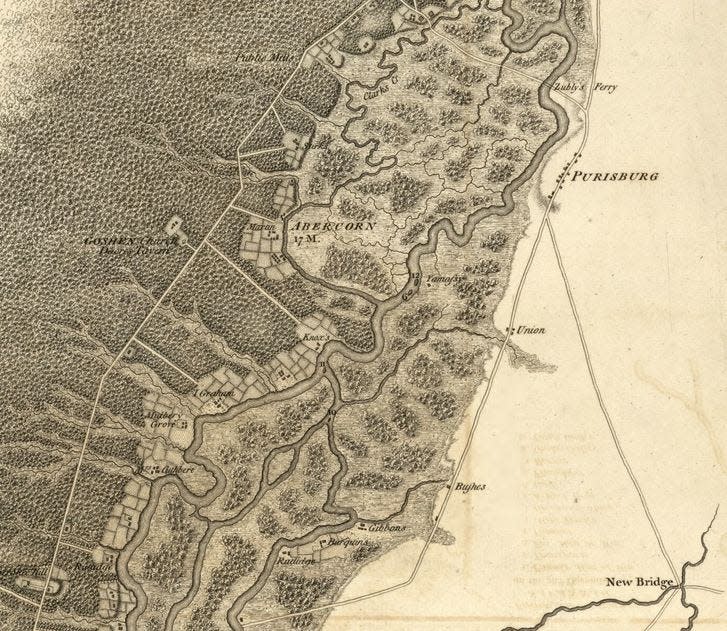

Go around 20 miles up the Savannah River towards Ebenezer Creek and you’ll probably miss the patch of trees once known as the Bear Creek Fortress. The name might fool you a bit, the fortress wouldn’t give off the same look as Fort Pulaski or Sumter.

Instead, it was one of many maroon communities in the United States –– an almost forgotten history of formerly enslaved people in the Lowcountry.

The “hidden fortress” will be investigated further in a discussion hosted by The Book Lady at The Learning Center with bestselling author George Dawes Green; award-winning historian of the African Diaspora, Sylviane Diouf; director of the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance, Paul M. Pressly; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region's Regional Historic Preservation Officer/Regional Archaeologist, Richard Kanaski.

More on The Kingdoms of Savannah: George Dawes Green explores local hidden history in his latest novel, 'Kingdoms of Savannah'

'It won't be the same city at all': Titan of Savannah knowledge John Duncan leaves mammoth legacy

How do we honor its conflicted history?: State's oldest plantation subsumed by industry

For many, this talk may be the first time hearing about maroon communities or the concept of marronage. Maroon communities were predominantly made up of escaped enslaved people who would marronage, or the act of extricating oneself from slavery, and live in an autonomous community.

The communities would be made up of a few houses and would be designed to allow the members to hide deep within the forests, bogs or swamps of the Lowcountry or Florida to make it difficult for others to find them.

While the act of marronage and these communities was well-documented in Latin America and the Caribbean, the ones in the United States have only started to become uncovered in recent decades. Most of that work comes from Dr. Sylvaine Diouf, starting with her book, “Slavery’s Exile: The Story of the American Maroons,” which was published in 2014.

Calhoun Square to lose its name?: What to know about latest plans to address controversy

“There was never a comprehensive study of maroons in the United States. I was actually not looking to write a book, I was looking to read books and studies about them, and I couldn't find any. So I wrote one,” Diouf said. “I was really interested in finding who they were, what they ate, what kind of clothes (and) what kind of shelter (they had)? I mean, really, to go very deep into the people and their way of life, and also the different kinds of marronage that exists.”

For the Bear Creek community, Diouf said it’s especially unique for the amount of people that were thought to be there (possibly over 100), the amount of land they had and the fact that it was the only fortified maroon community in the United States.

“What was really specific concerning (Bear Creek) was that it had a real war camp. First of all, it was a large company…it was about 17 acres so they planted corn and other crops. They had several houses, a sentry, etc. So it was a fortified camp and it’s the only one I found in the U.S.”

The fortification, or better yet, the ability of knowing how to fortify the camp, came from the start of the community following the Revolutionary War when enslaved people fought for the British as part of the Siege of Savannah. Their incentive was freedom after fighting and while the British didn’t win the war, they declined the invitation to move to an English settlement and decided to stay near the city.

Local column: Savannah's Black history is well-chronicled. Trolley tour operators must do better.

“There were a handful of them that started this. The first references (are) to 10 to 12 people plus women that founded this community. And that first community may have been on Abercorn Island, which is part of that Bear isle complex with Belleisle,” said Paul Pressly, who has been studying marronage explicitly in this region.

“They certainly did fight and one thing that needs to be emphasized is the fact that this is what’s not known, but recent research has shown that as many as 10% of the British troops were Africans and African-American. They provided that crucial difference in terms of manpower.”

George Dawes Green was turned onto the marronage of the Lowcountry by the late historian John Duncan, bringing it to the forefront of his latest novel, “The Kingdoms of Savannah.” For Green, there’s something impactful of reaching into these untold histories through the lens of a novelist.

“I’m looking at some questions of what it is that inspires us to find these communities; how the narratives that we hear about Savannah, how they really shaped the character of the city. This is a story that has never been told,” he said. “It’s been told in some history books, but it never reached the popular consciousness and it’s never reached our textbooks, and until now, I just think this is really an essential story to tell about Savannah’s history.”

More: Famed 'Midnight' Bird Girl photograph among Savannah items up for auction from Duncan collection

The event this week hopes to expand that — not only by creating a conversation around this history, but also pushing the narrative deeper to the popular consciousness. For Diouf, bringing these stories to the forefront are key in providing a richer, more varied account of American history.

“People know about the Underground Railroad, but the communities and individuals, and small groups, living in the swamps and forest, and living free as they wanted to — they define their own world, they define their own freedom and that part has been completely erased,” she said.

“In this country, the idea of freedom and autonomy, and self for Black people was not accepted, really. If you have Black resistance here (in the South), it’s really only runaways to the north (and they) were a small part of runaways in general. People from the Deep South; people from Georgia, South Carolina, etc. could never make it north. So this whole Underground Railroad thing, which is historical, it’s true. But it’s focusing on a very small part of the people who actually free themselves.

“Only the maroons were actually free. I mean, it was a very dangerous freedom. They were pursued by dogs and living among bears and whatnot; it wasn’t easy. But they were living in their own world.”

WHAT: Hidden Fortress: Fugitives, Marronage, And Black Resistance On The Savannah River

WHEN: Thursday at 7 p.m.

WHERE: The Learning Center, 3025 Bull St.

COST: $10-25

Zach Dennis is the editor of the arts and culture section, and weekly Do Savannah alt-weekly publication at the Savannah Morning News. He can be reached at zdennis@savannahnow.com or 912-239-7706.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Savannah GA events: Hidden Fortress discussion on marronage history