What to expect with DOJ's investigation into Memphis police: Taking a look at other cities

The U.S. Department of Justice late last month marked the Memphis Police Department as the ninth law enforcement entity to undergo a pattern or practice investigation under President Joe Biden's administration.

Investigations into two police departments, the Louisville Metro Police Department and Minneapolis Police Department, have been completed, with the DOJ concluding both displayed systemic problems and regularly deprived people of their constitutional rights.

Those investigations took place over the course of about two years, and the accompanying 90-page reports could offer a glimpse at what the investigation into MPD could yield.

All three investigations followed high-profile deaths. Police in Louisville shot and killed Breonna Taylor in 2020 while serving a no-knock warrant; a police officer in Minneapolis, Derek Chauvin, knelt on George Floyd's neck, depriving him of oxygen, in 2020 and was later convicted of murder; and five Memphis police officers have been charged with murder after beating Tyre Nichols, who died days later.

The DOJ opened a pattern or practice investigation into MPD just over six months after Nichols' death, taking about half as long to begin investigating as it did with the other departments.

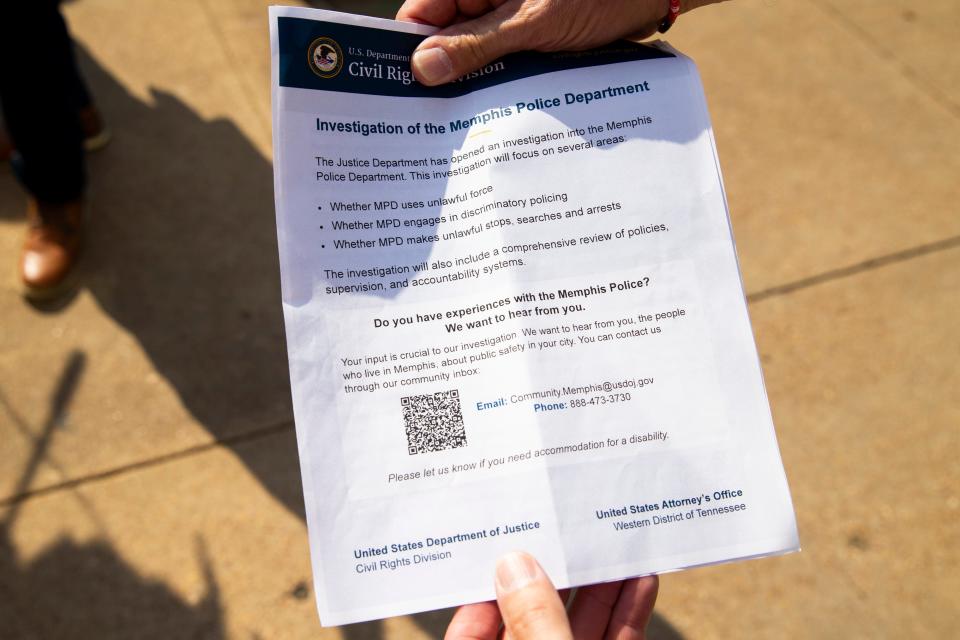

In announcing the investigation, the DOJ said it would focus on three areas in Memphis: MPD's use of excessive force, how the department conducts stops and searches, and whether MPD engages in discriminatory policing against Black residents.

The DOJ said Minneapolis police engaged in a pattern or practice of two of those investigative areas — using excessive force and conducting discriminatory policing — and that the LMPD, among several other findings, engaged in all three.

How departments compare in using excessive force

In both the Louisville and Minneapolis reports, the DOJ listed use-of-force statistics when talking about excessive force violations. The data presented looked over a five-year period and contained similar sets of data.

Those numbers, however, were slightly different and tailored to each report. the LMPD report listed police use of takedowns or strikes, chemical irritant spray, tasers, projectile launchers, batons and canine bite incidents.

The Minneapolis Police Department report listed the use of physical force, chemical irritant spray, tasers, less lethal devices and specified the department's use of neck restraints and officers unholstering or pointing their tasers.

According to the DOJ, there were 2,217 non-lethal use of force incidents between 2016 and 2021 in the LMPD, at a rate of about 433 incidents per 100,000 residents. There were 11,338 non-lethal use of force incidents in the Minneapolis police from 2016 to 2022, or about 2,668 incidents per 100,000 residents.

According to MPD's Investigative Services Bureau Dashboard, there were 5,945 non-lethal use of force incidents — about 959 incidents per 100,000 residents — from 2018 through the first three months of 2023.

MPD, however, leads those departments in how often an officer fires their gun. Over that same five-year period, MPD officers discharged service weapons at a rate of 6.61 times per 100,000 residents. LMPD and Minneapolis officers fire at a rate of 6.03 times and 4.47 times per 100,000 residents, respectively.

In the DOJ's investigation of LMPD, they found that officers "routinely" used force, even when there was no threat or resistance.

"Officers use force simply because people do not immediately follow their orders, even when those people are not physically resisting officers or posing a threat to anyone," the DOJ wrote in its report. "At times, officers use force to inflict punishment or to retaliate against those challenging their authority, in violation of both the First and Fourth Amendments."

LMPD similar to MPD in traffic stops, specialized unit use

During the course of the DOJ's investigation into LMPD, officials found the department's "proactive policing" through the use of pretextual traffic stops and hot-spot policing were conducted in a way that violated people's Fourth Amendment rights.

Almost a decade before MPD launched its since-disbanded SCORPION Unit to patrol crime hot spots around Memphis, LMPD established its own unit called the VIPER Unit.

SCORPION stands for Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods and VIPER stands for Violent Incident Prevention, Enforcement and Response.

Both units functioned in similar ways, with VIPER being described in the report as a unit that "engaged in aggressive pretextual enforcement" and would stop "people in certain neighborhoods for minor traffic infractions and other low-level offenses."

A Commercial Appeal investigation of SCORPION Unit arrest data found that more than 27% of charges the unit filed were driving-related.

In an interview with The CA in March, Shelby County District Attorney Steve Mulroy said the majority of SCORPION Unit cases stemmed from traffic stops, and that pretextual stops were the "automotive equivalent of stop and frisk." The SCORPION Unit was disbanded about three weeks after officers from the unit beat Nichols.

Most officers from the SCORPION Unit were moved to the Organized Crime Unit, which the since-deactivated SCORPION Unit was a branch of.

In Louisville, residents called "VIPER officers 'jump out boys' for their aggressive tactics," according to the DOJ report. Protestors there also called for the VIPER Unit to be disbanded, and it eventually was rebranded to the Ninth Mobile Division. Most officers from the VIPER Unit were placed in this newly named division.

Although the Fourth Amendment permits pretextual stops, they have long been criticized and require "officers to have legitimate grounds for each search, frisk or other investigative actions," the DOJ said.

In the DOJ investigation into LMPD, officials found that often officers conducting a traffic stop did not have consent, or adequate probable cause, to search people and their cars.

Without probable cause, police need people to consent to a search. That, in the case of the LMPD, was difficult since the DOJ found that sending multiple squad cars to a routine traffic stop "can be intimidating" and coerce someone to consent to a search.

"During stops, officers repeatedly ask for consent and pressure people into agreeing to searches," the DOJ wrote in its LMPD report. "One resident told us that officers asked to search his car so often, 'I started thinking the searches were part of being pulled over.'"

DOJ found Louisville, Minneapolis police discriminated against Black people

The DOJ also found that police in Louisville and Minneapolis discriminated against Black people in their policing. This included the distribution of when officers used force in an interaction, in traffic stops and in searches.

In Minneapolis, the DOJ broke down these discrepancies based on the racial makeup of the city. Beyond that, they also analyzed these numbers in instances where Black people and white people were reported to have behaved similarly, which was some of the reasoning for a search when someone was stopped.

In that additional analysis, the DOJ "found striking racial disparities in [Minneapolis police's] searches, suggesting [the Minneapolis Police Department] applies a different, lower standard when searching Black and Native American people."

In that analysis, Black people were subjected to 22% more searches, 37% more vehicle searches and 24% more uses of force.

Differences in the racial disparities between the Louisville and Minneapolis investigations and the investigation in Memphis could come from the racial makeup of the cities.

Memphis, according to the latest Census data, is the nation's largest predominantly-Black city, and 63% of the population is Black.

Black residents in Louisville and Minneapolis, however, make up 24% and 18% of the city's respective populations.

Of data available publicly on MPD's ISB Dashboard, however, a significant number of use of force incidents and incidents of officers firing their guns involve Black people.

According to that dashboard, from 2016 through the first three months of 2023, about 86% of MPD's use of force incidents involved Black people. About 75% of the people shot at by an MPD officer were Black.

How have these DOJ investigations finished?

Both of the DOJ's completed pattern or practice investigations ended with officials finding several violations within the LMPD and Minneapolis Police Department, and the federal agency and cities agreeing to negotiate a consent decree as a settlement.

Both departments, though acknowledging the need to reform the way the police departments operated, said they did "not concede that there is a pattern or practice of" unlawful behavior or constitutional violations.

Related news: Key takeaways from the DOJ's first meeting about its civil rights investigation into MPD

Once a consent decree is entered into by both cities ― though it is unclear when that will take place ― an independent monitor will be appointed to watch over the progress and ensure that the departments abide by the consent decree.

"The parties recognize that the process of reform is complex and will require sustained effort," the agreements read. "Reform will not occur overnight and will require clear goals and objectives. To this end, the parties commit to work collaboratively and earnestly and with necessary urgency."

Lucas Finton is a criminal justice reporter with The Commercial Appeal. He can be reached at Lucas.Finton@commercialappeal.com and followed on Twitter @LucasFinton.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: DOJ investigation into Memphis police: What city should expect as outcome