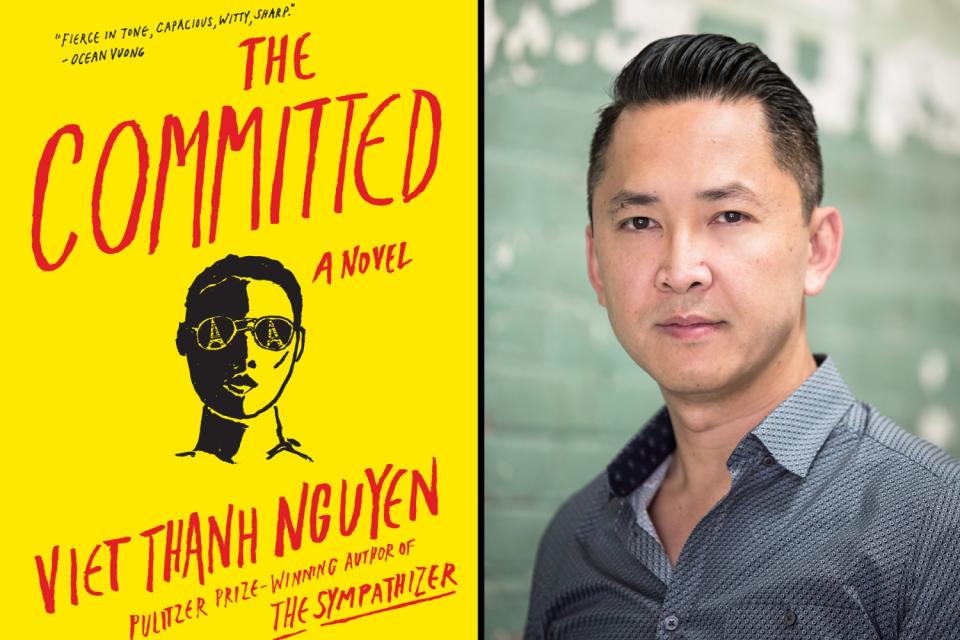

What to expect in Viet Thanh Nguyen's sequel to his Pulitzer-Prize winning 'The Sympathizer'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s debut novel “The Sympathizer” introduced readers to its unnamed protagonist, a half-Vietnamese, half-French communist double agent navigating life, love, loyalty and espionage in Los Angeles after the fall of Saigon.

In Nguyen’s sequel, “The Committed,” his narrator is “still a man of two faces and two minds.” But now he is also “a revolutionary without a revolution,” a refugee in 1980s Paris who is grappling with politics, ideologies, and himself.

“I wasn't done with his story,” says Nguyen, who joins the Los Angeles Times Book Club on March 10. “I’m very cognizant of the fact that people read “The Sympathizer” as a Vietnam War novel and me as a Vietnamese American writing about the Vietnam War.”

The sequel, he says, allowed him “to expand upon what I've always felt, which is that ‘The Sympathizer’ is not only a Vietnam War novel but a novel about race and colonialism.”

By all measures, “The Sympathizer” is a tough act to follow: a bestseller that drew comparisons to Ralph Ellison, John le Carre and Saul Bellow, the novel earned the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. But “The Committed” is both a seamless continuation of its predecessor — the same unsparing intellect and take-no-prisoners sardonic wit animate each page — and a stand-alone book.

Like “The Sympathizer,” “The Committed” strides genres. Nguyen delivers a literary thriller that’s part political novel, part historical novel and part comic novel. He trades the conventions of the spy novel of the first book for crime. Gangsters, drug dealing, turf wars and shootouts propel hairpin plot-twists and belie an ambitious book of ideas.

“I thought that there would be a sweet spot for readers who would be willing to grapple with serious ideas and be entertained at the same time,” Nguyen says.

Nguyen, 49, is the author of six books, including “The Refugees,” a bestselling short story collection, and “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War,” a National Book Award finalist in nonfiction. Until recently, he wrote from a spare bedroom in Silver Lake where he lived for 20 years before his family relocated to Pasadena to give his 7-year-old son, Ellison, more space to play. He spoke to the Times on Zoom from his book-lined home office where Ellison entertained himself in the background, occasionally approaching the screen to smile and wave.

A USC professor, Nguyen notes that contemporary American literary fiction often lacks the sense of setup and suspense more often seen in so-called genre writing, and he chooses instead to embrace the page-turning quality of a good plot in his own work. Nguyen has been praised for his biting satirical humor, which he deploys to similar effect. “Laughter just makes things go down easier,” he says.

Nguyen cites Shakespearean tragicomedies and Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels as inspirations for “The Sympathizer” and “The Committed.” He also cites the action films of John Woo. Part of the drama of both novels is the relationship between the narrator and his blood brothers, a communist and a killer of communists, both of whom he betrays and both of whom he loves.

“I was deeply influenced by watching films like 'A Better Tomorrow' and 'A Bullet in the Head,' which is actually set in Vietnam… It’s that same sense of romantic blood brotherhood, the good guy versus bad guy who are actually mirror images of each other.”

For a writer adept at penning thrillers, it might come as a surprise that Nguyen also names as a major influence W. G. Sebald, the German writer known for hybrid works exploring loss, memory and the aftermath of World War II, although the connection is less technical than thematic. Like Sebald, Nguyen partly preoccupied with the historical events that informed his life.

Nguyen was 4 years old when his family fled Vietnam and landed in a Pennsylvania refugee camp, at which point he was separated from his parents for several months before being reunited and settling in California in the late 1970s. His parents opened one of the first Vietnamese grocery stores in San Jose.

“My memories begin with being separated from my parents as a part of the refugee experience,” Nguyen says, “That left a deep imprint on me.” He describes the separation as well-intentioned — an attempt to help his parents get on their own two feet — but profoundly wounding.

“As a child, you just interpret it as abandonment. I spent most of my life trying to not think about that... So it’s been very, very difficult, as a writer, to excavate myself because that's where the material is. The real material is what's inside: the emotions, the contradictions, the damage, the hurt and the harm that most sensible people don't want to have to confront. But as a writer, I think that's absolutely necessary.”

In the complex and fractured protagonist of the novels, Nguyen has created a character through which to tap the vein. He describes him as his alter ego. An interrogator of fellow spies and rival gangsters, the character is also a relentless interrogator of ideologies and the failings of all people, on all sides.

“In both of these books, I wanted to be as unrelenting as possible in terms of both interrogating these dominant cultures of the United States and France, but also interrogating the narrator and interrogating the communities that he is involved with.”

In “The Committed,” the man of two minds remains alert to ambiguities, contradictions and double-meanings. “Continuing his misadventures is continuing my interrogation of him, but also my interrogation of myself,” says Nguyen.

One of the many strengths of Nguyen’s writing is that nothing is spared from his clear-eyed analysis: not France, the United States or Vietnam, not communism or capitalism, not his characters and most importantly, not his own work. In “The Sympathizer,” he concedes, “there's a lot of sexualization and objectification of women, discussions of [the narrator’s] virility, that kind of thing. I had a lot of fun, then halfway through the book, I thought, ‘Wait a minute, I'm having too much fun; I'm enjoying this'.”

Nguyen saw the realization as an opportunity. “’The Committed’ takes on his masculinity and heterosexuality and sexism and patriarchy,” Nguyen says, “and his gradually dawning understanding that his investment in them has these terrible outcomes.” Secondary characters and subplots, including one loosely inspired by the sexual scandals of French socialist Dominique Strauss-Kahn, further dramatize this exploration. Nguyen hopes that the book “models this kind of necessary interrogation.”

“It doesn't matter whether you're on the left or the right or where your political convictions happen to be. There's still a trade and commerce in the objectification and exploitation of women that all these men with all their pretensions participate in and that's partly what's being satirized in “The Committed.”

Between teaching and the demands on his schedule as a public literary figure (he recently became the first Asian American member of the Pulitzer Board), Nguyen is intentional with his time. The packed bookshelves in his office are designed to keep literature front-and-center; he records each book he reads — for tenure reviews, prize deadlines and pleasure — in a spreadsheet.

“The only things I don’t put on there are his books,” he says, nodding toward Ellison. “But maybe I should… Why not? Children’s books should count.” Father and son do more than read together: in 2019 they co-authored “Chicken of the Sea,” in which a band of chickens join the ranks of a pirate ship and seek adventure.

Lately, Nguyen has returned to nonfiction and is working on a memoir that takes up the problem of representation in literature.

“So-called minority or multicultural writers are only supposed to represent ourselves, whereas the unmarked writers, the people who are just writers get to represent everybody,” says Nguyen. “I knew my own work would be bracketed in this way, that the first reflex that people would have picking up my novels would be to say, ‘He's a Vietnamese guy writing about Vietnamese stuff.’ And I had to take a position where I say, ‘I am a Vietnamese guy writing about Vietnamese stuff, and that's not a limitation any more than John Updike writing about people from New England is a limitation.”

As an artist, his challenge is to work against the limitations imposed by that assumption, in part by creating a protagonist who insists, “to say we were all human was merely sentimental, but to say that we were all inhuman was the truth.”

“Inhumanity is humanity,” says Nguyen. “That's the kind of complexity I think art should reach for and which I hope my novels do.”

In addition to the memoir, Nguyen also plans to turn his pair of novels into a trilogy. “The Committed" will be followed by an “epic crime-gangster-spy novel.”

“The final installment is going to be back here in the United States,” Nguyen says. In the third book, “the man of two faces and two minds” returns to L.A. to “either seek revenge or make amends or both. We’ll find out.”

Book Club: If you go

Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of “The Committed,” joins the Los Angeles Times Book Club in conversation with columnist Carolina A. Miranda.

When: March 10 at 7 p.m. Pacific

Where: Free live streaming event on Facebook, Youtube and Twitter. Sign up on Eventbrite here.

More info: latimes.com/bookclub

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.