Experts believe negligence contributed to a baby's death. Wisconsin laws don't make it worth it for anyone to take the case.

Read part one of the story: Born with a treatable condition at a Milwaukee hospital, she died 30 hours later. What happened to Baby Amillianna?

Karen Ramirez and Justin Johnson just wanted to know why their daughter, Amillianna, had died.

Born on Sept. 18, 2021, she was pronounced dead in Ramirez's arms 30 hours later at Ascension Columbia St. Mary's hospital in Milwaukee.

They asked for medical records and requested meetings with hospital staff who had cared for her during her short life.

Ascension Columbia St. Mary's dribbled out records, making it difficult for them to piece together a timeline of Amillianna's care or even take the matter to an attorney.

Early attempts at a meeting fell through when Amillianna's parents were told the nurses and doctors who cared for their daughter would not be part of discussions. Later, they were told two doctors involved in her care no longer worked for Columbia St. Mary's.

Within weeks of Amillianna's death, a hospital official told Ramirez they would no longer talk with Johnson, further straining communication efforts.

"Our plan is to have a conversation with you and to talk about everything. But from here on out, we will not be communicating with him," a hospital official told Ramirez, according to an audio file shared with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

No reason was given by the official for this decision during the call.

The Journal Sentinel provided the hospital with a list of questions about the case in mid-January, but officials initially refused to offer more than a general statement citing patient privacy. After the Journal Sentinel sought and obtained signed permission from Amillianna's father, Justin Johnson, for the hospital to discuss her care, the hospital issued a new statement Wednesday evening.

That statement did not directly address any of the questions − including the phone call and how Johnson was treated.

"The loss of any child is tragic and our hearts and prayers go out to this family," an Ascension Wisconsin spokesperson said in the statement.

Distrustful of the hospital and its staff and convinced Amillianna had not received proper care, Johnson, with Ramirez's support, turned to Wisconsin's justice system to seek accountability for their daughter's death.

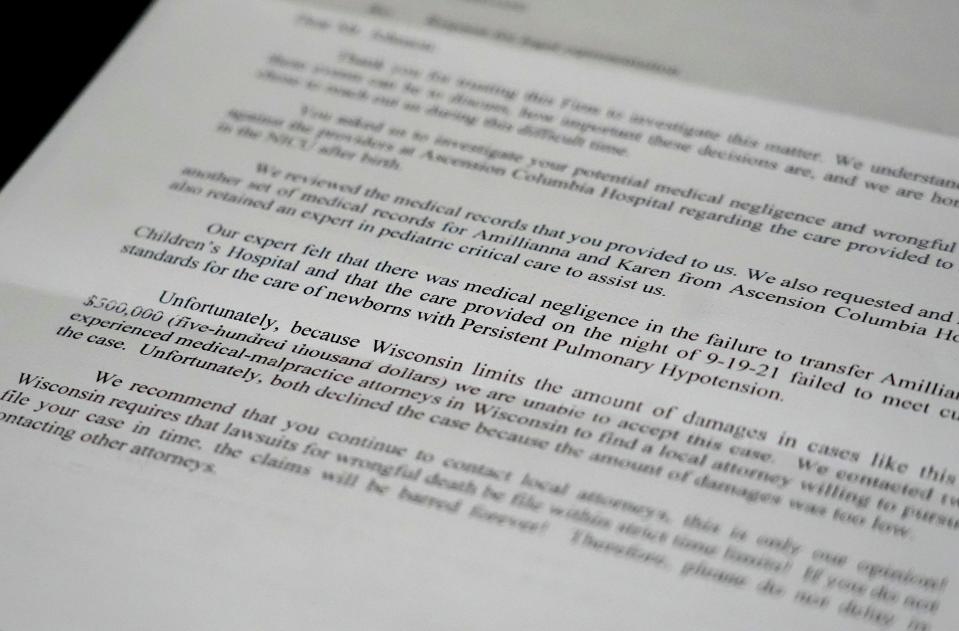

One attorney investigated and believed, based on a medical expert's opinion, that there was a case of medical malpractice — only to realize that Wisconsin's medical malpractice cap made it "financially restrictive" for his firm to take it to court.

At this point, it is a race against the clock. Johnson and Ramirez are roughly seven months away from hitting Wisconsin's three-year statute of limitations on filing a medical malpractice case.

A law firm finds a seemingly clear-cut case

By January 2023, Johnson had spent months combing online media sites, looking for examples of medical malpractice cases where the family successfully held a hospital responsible for the death or injury of a child.

"Money will not bring her back and it doesn’t equal justice," Johnson said. "We want an apology. We want them to admit what they did wrong. We don't want another child to receive this level of care."

On Jan. 11, he called Murphy, Falcon & Murphy, a Baltimore-based firm he found mentioned in a news article.

He was connected with Nicholas Szokoly, who represents patients and health care systems in medical malpractice cases. A father himself, Szokoly felt a bit of a connection to this stranger calling from Milwaukee. He thought Amillianna's death was "worth looking into."

Initially, he had little to go on. Amillianna's parents had continued asking the hospital for records without much success. They were initially given 19 pages, then another 47 more pages in September 2022, a year after her death.

"They were slow-walking this information out to a father whose daughter had just died," Szokoly said.

When the firm made a records request, with the family's support, under the federal HITECH Act, it received hundreds of pages of documents.

Johnson sent the limited records he was given by Ascension to six law firms prior to Szokoly. All declined the case. Some provided no reasons, while others said proving negligence would be too difficult to justify the risk of going forward based on the information they had at the time.

"I think the way the family was treated stinks to high heaven," Szokoly said. "They asked twice for records. All the records should have been given to them. I've never seen a problem like that with any other hospital."

By the end of February 2023, Szokoly had consulted with a board-certified pediatric critical care doctor with more than 20 years of experience, who reviewed Amillianna's records and Ramirez's records. The consulting physician has testified as a medical expert for the firm on behalf of plaintiffs and defendants.

The expert came to the following conclusions concerning Amillianna's care at Columbia St. Mary's:

Hospital staff failed to meet standards of care when treating Amillianna for persistent pulmonary hypertension due to meconium aspiration.

Hospital staff committed medical negligence in its failure to transfer Amillianna to Children’s Wisconsin hospital for a higher level of care.

An Ascension Wisconsin spokesperson said in the Wednesday statement that its "thorough internal review found the standard of care provided to this patient was met by the clinical team."

However, the previous day, Dr. Chintan Desai, Ascension Wisconsin's chief medical officer, said in an emailed statement to the Journal Sentinel, that "many factors influence medical decision-making." Desai made no mention of the internal review.

"It's important to recognize that the standard of care could be met by various methods of treatment and that one method is not inherently superior to another, as patients may have varying responses to identical treatments," Desai said in the statement. "The application of guidelines should be tailored to the specific clinical situation."

In Szokoly's view, Amillianna's care illustrated the hospital's culture of safety.

"She wasn't suffering from a condition that required seeking advice from the Mayo Clinic or Johns Hopkins," Szokoly said. “It is not a medical mystery. It is just bad management."

But his effort to find them justice hit a wall: Wisconsin's medical malpractice law.

'Nobody is ever going to take your case'

Wisconsin law caps medical malpractice at $500,000 in the case of a death of a minor child, which makes it cost-prohibitive for many firms to accept these cases and argue them in court.

Pretrial costs, including the money needed to pay expert medical witnesses, can eat up $80,000 before the trial even starts, Szokoly said. If the family wins, the remainder of the $500,000 is essentially split between the family and attorney fees, meaning each receives about $200,000.

In contrast, the equivalent cap in Maryland, where Szokoly's firm is based, is adjusted annually by $15,000. It is currently $1.12 million.

Szokoly's firm decided against taking Amillianna's case; it was not financially viable to do so.

Szokoly said he contacted two experienced medical malpractice attorneys in Wisconsin in hopes of finding a local attorney willing to pursue the case. Both declined to take the case for the same reason as Szokoly's firm; the amount of damages was too low.

"All I want is to find this case a home," Szokoly said. "I have the records. I have an expert lined up. I'm not even interested in sharing (attorney) fees."

Szokoly called Johnson to explain.

“Your baby is dead and you’ve got a case. But nobody is ever going to take your case because your state’s medical malpractice caps are too low,” Szokoly remembers telling him.

“It is a horrible phone call to have to make.”

For Johnson, it was a blessing that someone finally believed what he and Ramirez believed, that Amillianna did not receive proper care.

"For a while, it was like watching a horror movie. You can’t believe what is happening,” Johnson said. “But it’s worse because it’s your life and nobody is responding to what you are telling them is happening. You feel like you’re losing your mind.”

Szokoly put a stop to that.

"He took the time to investigate, to dig and ask for more records," Johnson said. "I know he tried. For that, I am grateful."

'There is nothing for a family like this to do'

Amillianna's parents are not alone in their inability to find an attorney willing to take their daughter's case.

In 2014, a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigation found the total number of medical malpractice lawsuits filed in Wisconsin fell to 140 in 2013, a drop of more than 50% since 1999.

The drop continues, with the number of cases filed dwindling to 87 in 2022, the most recent year available, according to electronic court records.

Malpractice lawyers blame the decline on state laws that they say are skewed in favor of doctors and hospitals; medical groups contend that malpractice suits have declined because health care professionals have gotten better at their jobs.

Wisconsin's medical malpractice laws include:

Only spouses and minor children can sue for loss of companionship in a medical malpractice death when an adult dies due to medical negligence. Parents are not entitled to bring a case when an adult child dies.

$750,000 cap on “non-economic” damages — such as claims that malpractice caused pain and suffering or loss of companionship

$500,000 cap on damages for "loss of companionship" in the wrongful death of a minor

$350,000 cap for an adult in a wrongful death case

$250,000 cap in malpractice lawsuits involving doctors employed by the state, a category that includes the more than 1,670 faculty physicians employed by UW–Madison. The cap applies even if a doctor’s negligence results in a lifetime injury that will require millions of dollars of future treatment.

Meanwhile, the state-run Injured Patients and Families Compensation Fund continues to grow, a result of so few medical malpractice lawsuits being filed in the state. As of June 2022, the fund contained $1 billion. Medical malpractice payouts are so few that health care professionals who are required to annually pay into the fund have not had to do so since 2020, according to the state insurance commissioner’s office.

“Cap-wise, it is one of the worst laws I’ve seen. There is nothing for a family like this to do,” Szokoly said. “They fall in the crack.”

In 2018, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled the $750,000 cap on “non-economic” damages, which includes pain and suffering, was constitutional. The case also involved care provided at Columbia St. Mary's.

As a result of that ruling, plaintiffs Ascaris and Antonio Mayo ended up receiving less than 5% of the $16.5 million in noneconomic damages that a Milwaukee County jury awarded them in 2014.

When she was 50, Ascaris Mayo lost her limbs after medical personnel at Columbia St. Mary's Hospital failed to diagnose an infection or offer her antibiotics to treat the condition. Her Strep A infection ultimately led to septic shock and sepsis and the amputations.

A bill was introduced in January by Assembly and Senate Democrats that would increase the $750,000 "non-economic" damages cap to $3 million, but it is unlikely to move forward this year.

A case has never challenged the $500,000 cap that is preventing Amillianna's parents from having their day in court.

"It is a cruel fact to know nobody will ever take the case to court," Johnson said. "We don’t know how many people were in our situation before and there will be more after us. It just can’t keep going on. No one is getting help."

Johnson also submitted a complaint, via an online portal, in July with the Wisconsin Department of Safety and Professional Services. He was told Monday the case has yet to be assigned to anyone.

Living disparities

Wisconsin’s overall infant mortality rate — the number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births — was 5.7 for 2019-2021, data from the state’s Maternal and Infant Mortality Prevention Unit show.

Black babies in the state face the worst outcomes by far, with a mortality rate of 13.2 deaths for every 1,000 live births. Amillianna’s mother is Puerto Rican and Black. Her father is Black, Blackfoot Sioux and Cherokee.

Data and studies nationwide show that the differences in mortality rates between races are preventable, and are driven by social and economic factors and by biases in health systems and their employees.

Implicit bias is learned behavior and thoughts about different groups of people. The bias is expressed subtly, not as in-your-face racist or derogatory words.

It creeps into a patient's care when health care workers ignore concerns, minimize pain or blame a patient for their inability to find child care or a ride to keep an appointment, said Erin Murders, an educational instructor who teaches how implicit bias and structural racism affect perinatal care for the Association of Women's Health, Obstetrics and Neonatal Nurses.

She said she believes there is an indication of implicit bias in Ramirez's prenatal care records from Milwaukee's Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers, which offer free or low-cost care.

Citing patient privacy laws, Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers declined to comment on the care Ramirez received.

Ramirez's medical records show her being described as “irritated" when staff called to check on why she missed an appointment, and "not receptive" to scheduling others. Murders said her records should have been straightforward chronicles of her care.

Ramirez said she received good care from Sixteenth Street. But Murders noted that labeling a patient — as staff did with Ramirez — can negatively influence the care the patient receives from other providers.

The unspoken feeling is that “we are not going to give 100 percent if the patient isn’t giving 100 percent,” Murders said.

Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers declined to comment on whether its staff receives implicit bias training.

A year and a half after Amillianna's death, Johnson saw Dr. Jasmine Zapata on a Fox 6 newscast detailing the state's infant mortality numbers. For the first time, he heard a health care professional talking about racial disparities in health care and why they exist.

"Oppressive systems carry the blame for many of these inequities," Zapata, the state’s epidemiologist for maternal and child health, said in the interview, "not the individuals."

Johnson said he didn't grow up believing people were different or treated differently because of the color of their skin. His thinking has changed.

“When it comes to cases like this and my skin color is like this – it’s the only thing I can think of,” Johnson said.

Always in our hearts

On an unseasonably warm December day in Milwaukee, sunshine beams down on the words of the freshly inscribed headstone:

“Always in our Hearts. Amillianna Ka’Linda Ramirez-Johnson. Sept. 18, 2021 - Sept. 19, 2021. We love you.”

Johnson made the final payment for Amillianna's headstone in October, officially marking the final resting place for Amillianna, more than two years after her birth and death.

He visits the gravesite alone. He and Ramirez haven't been there together since burying their daughter.

Ramirez and Johnson's relationship began to unravel as they grieved Amillianna's death and faced setback after setback in their quest for answers. They remain in contact, but the more time passes since their daughter’s death, the less frequently they talk.

When the story of her life makes him feel hopeless, he said he finds strength to keep telling her story, keep fighting for answers, in an ultrasound image of Amillianna taken around 24 weeks. A copy goes everywhere with him and electronic versions of it are saved on all his devices. It is an image he and Amillianna's mother know well.

At the time it was taken, they thought it was cute. Amillianna had her hands together, her arms bent at the elbows.

It looks like she is praying.

How we reported this story

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Jessica Van Egeren first began researching overworked staff and concerns surrounding patient safety at Ascension Columbia St. Mary's hospital in Milwaukee at the end of 2022. This reporting led to families stepping forward to share their own experiences.

One such experience came from Tanzanique Carrington. Her husband, Keith Carrington, died at the hospital on Aug. 22, 2023, following a surgery to amputate four of his toes. He was 48.

Carrington believed "lackadaisical care" led to his death. She was never able to find an attorney to take his case and her misconduct/complaint of care report filed with the Wisconsin Department of Health Service's Division of Quality Assurance found no violations in her husband's care. To this day, she believes his death was due to a blood clot, not septic shock.

Justin Johnson, Amillianna's father, saw the story. He contacted Carrington, a principal at a Milwaukee middle school, who put him in contact with Van Egeren. She obtained permission from Johnson and Amillianna's mother, Karen Ramirez, to access their medical records from Ascension Columbia St. Mary's hospital and Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers where Ramirez received her prenatal care.

Attorney Nicholas Szokoly with Murphy, Falcon & Murphy obtained permission from Johnson to share with Van Egeren additional medical records that he had requested from the medical centers. Szokoly's medical expert reviewed the medical records and believed Ascension Columbia St. Mary's did not follow standards of care when treating Amillianna and was medically negligent in its failure to transfer Amillianna for a higher level of care.

Szokoly also obtained permission to discuss these findings with Van Egeren. Ascension Columbia St. Mary's and Sixteenth Street Community Health Centers declined opportunities to comment on Amillianna and Ramirez's care, citing state and federal privacy laws.

Van Egeren, a licensed registered nurse who previously worked as a cardiac nurse in a Madison hospital, pored over the hundreds of pages of records. She then sought out medical professionals with expertise in the areas of care relevant to Amillianna and her mother.

Finally, Amillianna's parents spent an untold number of hours detailing the loss of their daughter and what life has become since her passing. Amillianna's story is the culmination of those interviews and six months of research into her care.

The Journal Sentinel provided the hospital with a list of questions about the case in mid-January, but officials initially refused to offer more than a general statement citing patient privacy. After the Journal Sentinel sought and obtained signed permission from Amillianna's father, Justin Johnson, for the hospital to discuss her care, the hospital issued a new statement Wednesday evening.

That statement did not directly address any of the questions, other than to say broadly that its "thorough internal review found the standard of care provided to this patient was met by the clinical team."

Jessica Van Egeren is the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel's enterprise health reporter. She can be reached at jvanegeren@gannett.com or 608-320-3535.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Medical malpractice caps leave parents lawyerless after baby's death