Experts Fear Lab-Grown Brains Will Become Sentient, Which Is Upsetting

The idea of sentient, lab-created "organoids" raises ethical questions that ripple through science.

Tests could include physical scans, mathematical models, and more.

Scientists say there are reasons it could be necessary to create consciousness ... and destroy it.

A thought-provoking new article poses some hugely important scientific questions: Could brain cells initiated and grown in a lab become sentient? What would that look like, and how could scientists test for it? And would a sentient, lab-grown brain “organoid” have some kind of rights?

DIVE DEEPER. ➡ Get unlimited access to the weird world of Popular Mechanics , starting now.

Buckle up for a quick and dirty history of the ethics of sentience. We associate the term with computing and artificial intelligence, but the question of who (or what) is or isn’t “sentient” and deserving of rights and moral consideration goes back to the very beginning of the human experience. The debate colors everything from ethical consumption of meat to many episodes of Black Mirror.

Here’s how the Stanford Dictionary of Philosophy describes sentience:

“An animal, person, or other cognitive system [...] may be conscious in the generic sense of simply being a sentient creature, one capable of sensing and responding to its world. Being conscious in this sense may admit of degrees, and just what sort of sensory capacities are sufficient may not be sharply defined. Are fish conscious in the relevant respect? And what of shrimp or bees?”

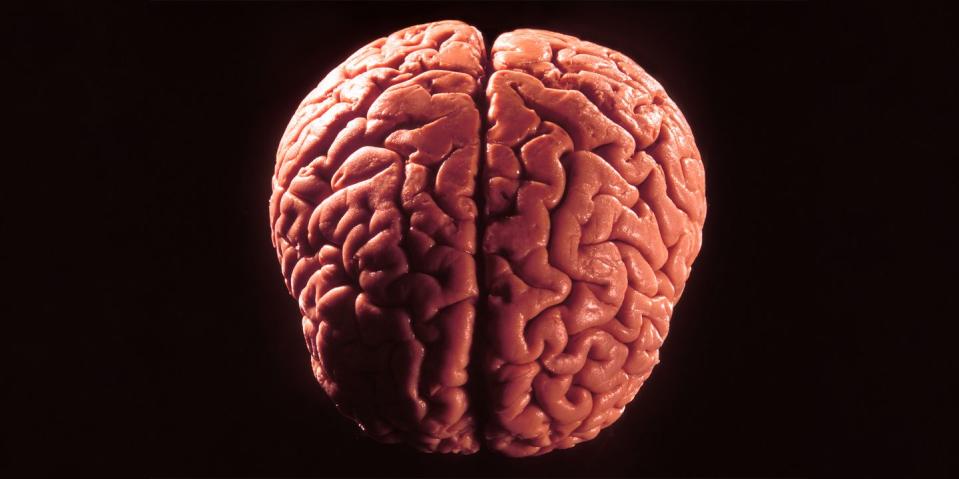

In Nature, reporter Sara Reardon explains a specific area where the debate over sentience gets very heated, very quickly. In August 2019, Alysson Muotri, a professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Cellular & Molecular Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, published a paper with colleagues in Cell Stem Cell on the "creation of human brain organoids that produced coordinated waves of activity, resembling those seen in premature babies."

And those waves, Reardon reports, continued for months before Muotri and his team ended the experiment.

That means the cells Muotri's group was making in the lab were exhibiting the beginnings of being a “cognitive system” that might end up “sensing and responding to its world” in some way.

📚 The Best Books on Consciousness

In the wake of experiments like Muotri's—Reardon references other similar studies in the Nature piece—scientists with the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine now want to establish a set of guidelines "to guide the humane use of brain organoids and other experiments that could achieve consciousness," just like the rules researchers abide by when studying animals.

In this ongoing study, which began this past June, a committee is examining all relevant research in attempts to answer ethical questions associated with brain organoids and human-animal chimeras. These include:

How would researchers define or identify enhanced or human awareness in a chimeric animal?

Do research animals with enhanced capabilities require different treatment compared to typical animal models? What are appropriate disposal mechanisms for such models?

How large or complex would the ex vivo brain organoids need to be to attain enhanced or human awareness?

Should patients give explicit consent for their cells to be used to create neural organoids?

Human development and capacity have always formed a key analogy that ethicists and moral philosophers grapple with. Utilitarian philosopher and general “living things” rights advocate Peter Singer made a famous argument that an especially brilliant chicken or other livestock animal might surpass some humans in at least some capacities—yet, he argued, we treat them very morally differently. You can already see how the debate grows contentious and divided.

But Muotri is tackling this problem head on, and on purpose.

“Muotri and many other neuroscientists think that human brain organoids could be the key to understanding uniquely human conditions such as autism and schizophrenia, which are impossible to study in detail in mouse models,” Reardon explains in Nature. “To achieve this goal, Muotri says, he and others might need to deliberately create consciousness.”

Other thorny parts of research include reviving recently deceased brains, but that’s still considered separate from a sentience that humans totally artificially generate. Tests for “sentience” may include mathematical models based on density of neurons, Reardon explains, or medical scans of “brain” activity. Any real ethical standard will likely include a number of criteria that scientists can turn into a compound metric.

For scientists who are already used to using quite intelligent lab animals in destructive (in the literal sense) testing, the difference may seem small, or even negligible. But that’s part of why ethicists exist: to ask hard questions and push scientists to answer them.

You Might Also Like