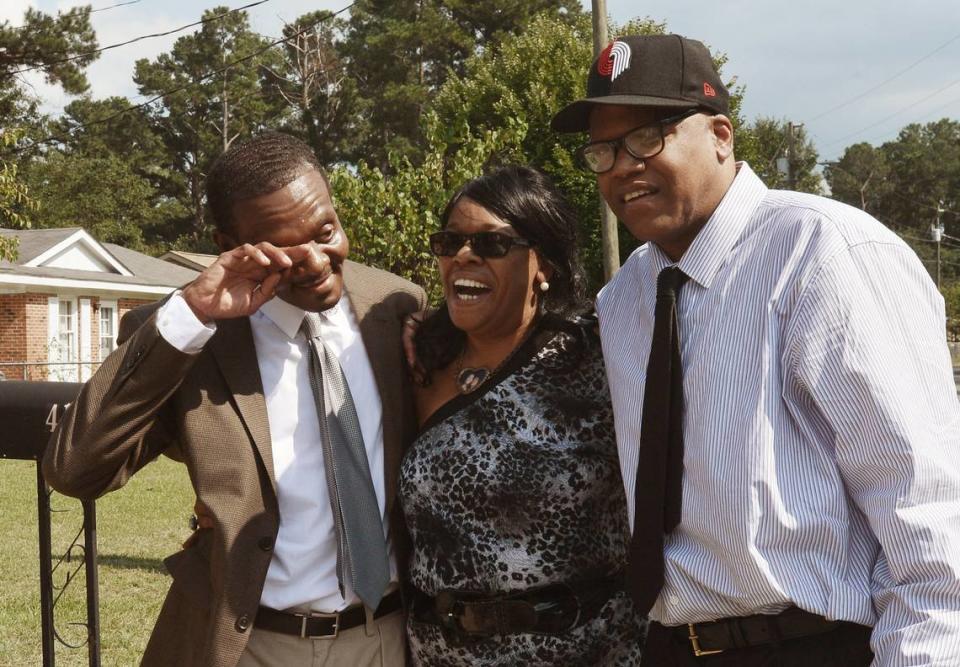

Exploited for decades, wrongfully convicted brothers are now ready for a fresh start

For nearly 40 years, Henry McCollum and Leon Brown’s lives have been defined by others who have victimized and exploited them.

The cycle began, in a life-changing way, the night in September 1983 that law enforcement officers coerced them into signing confessions to a rape and murder they did not commit. It continued for decades.

“It’s been a constant problem,” Kenneth Rose, an attorney who worked on McCollum’s case for 20 years and long believed in his innocence, said during a recent interview. “It was a problem in prison. It was a problem when they were convicted, and when they were interrogated.

“It was a problem when they were released.”

Now, after what might be the largest wrongful conviction judgment in American history, McCollum and Brown, half brothers who suffer from intellectual disabilities, will depend on guardians and the courts to offer protection from those who might try to target them.

The brothers were teenagers with IQs in the 50s when they were charged in the death of an 11-year-old girl in Red Springs in 1983. Police interrogated them for hours on the basis of a false rumor and later insisted the brothers confessed. McCollum and Brown maintained for decades that they were tricked into signing those confessions; that they didn’t understand them and that they feared if they did not sign them they could be sent to the gas chamber.

After nearly 31 years of wrongful incarceration, and after pursuing a federal civil rights case that began in 2015, McCollum and Brown received some measure of redemption late last week in a federal courtroom in Raleigh. A jury awarded them a $75 million judgment, including $31 million each in compensatory damages, against law enforcement behind their convictions.

“I thought that Henry and Leon were vindicated,” Rose, the former director of the Center of Death Penalty Litigation in Durham, who testified in the civil trial, said this week. “And that it was an important step to giving them the justice that they deserved, and also holding the persons who had wronged them — and I’m specifically thinking about the SBI agents, and the former sheriff, Mr. (Kenneth) Sealey — holding them accountable for misconduct.”

The outcome of the civil case is one the brothers and their lawyers, led by a team from the Washington, D.C. branch of the firm Hogan Lovells, had sought for years.

Yet the considerable court victory, which comes amid a national reckoning of police misconduct and mistreatment of Black people, also comes with an important question. How will the brothers, who became victims of fraud and poor financial management after their exonerations in 2014, protect themselves against the unscrupulous and others who might target them and their money?

A previous lawyer’s misconduct

“It’s hard to say this,” Rose said, but in one way he has found reason to be thankful for the result of what McCollum and Brown endured after the emergence of DNA evidence exonerated them more than six years ago. At the time, Rose was involved in the brothers’ pursuit of full pardons of innocence from the state.

Soon, though, a Florida lawyer named Patrick Megaro came to represent the brothers, and forced Rose off the case. Over the next two years, Megaro and his associates continued the cycle of exploitation of McCollum and Brown. Court records detail how Megaro kept $500,000 from the brothers — one-third of the $750,000 they each received from the state following their pardons.

Megaro also involved the brothers in predatory loans and complex fee arrangements that promised him between a 27% and 33% stake in any settlement or judgment resulting from the civil case, which he first filed in 2015. In 2017, McCollum’s court-appointed guardian ad litem, a Raleigh attorney named Raymond Tarlton, began to suspect that Megaro was defrauding the brothers.

“My fear was that they were creating a conflict of interest in the litigation — just on the one hand to say the brothers could manage millions and the fee arrangement and on the other say they don’t understand what happened in the interrogation room (in 1983),” Tarlton said in a recent interview.

Then, Tarlton said, “after the first meeting with the Florida lawyers, I knew that they were downplaying predatory loans.”

Tarlton described as “just absurd” the exorbitant fees that Megaro was charging, as well as the notion that McCollum and Brown, given their intellectual disabilities, could have competently agreed to surrender as much as 33% of any settlement or judgment.

A federal judge barred Megaro from the case in 2018, and in March the North Carolina State Bar suspended his license for five years and ordered him to repay $250,000 of the money he took from McCollum and Brown. Megaro’s misconduct during the civil case was “so blatant,” Rose said, that it “forced the actors in the system to ensure that (McCollum and Brown) were protected. And I am so grateful for that.”

By 2018, Brown, who has been living in a group home not far from Red Springs, had received a court-appointed guardian in Fayetteville, where he and McCollum had lived for a time with their sister. Brown suffers from mental health conditions related to his years in prison. McCollum, who lives in a small Virginia town near the North Carolina state line, has a guardian from Richmond.

“It was a free-for-all with the former lawyers,” said Tarlton, who played a leading role in assembling the team of attorneys who worked on the case the past few years. The team from Hogan Lovells worked the case pro bono, with local assistance from Elliot Abrams, a Raleigh lawyer who expressed confidence that the brothers will be protected from further financial exploitation.

“There are court-appointed guardians whose conduct will be overseen by the court,” Abrams said this week, “who will specialize in making sure that (McCollum and Brown) are able to balance their freedom to make choices and do the things they want to do while protecting them from people who are trying to take advantage of them, first and foremost, and secondly from decisions that will cause them to end up without enough money to care for themselves at the end of their lives.

“I have every belief that this money will not be squandered, and that they won’t be defrauded of it, either.”

The timeline for receiving money

In addition to the $75 million judgment, the brothers received a $9 million settlement from the Robeson County Sheriff’s Office, which settled moments before closing arguments were to begin in the civil trial. Former Robeson County Sheriff’s deputies Garth Locklear and Kenneth Sealey, as well as former SBI agents Leroy Allen and Kenneth Snead, were all named in the civil suit. All played leading roles in the investigation behind the brothers’ convictions.

The $9 million, to be divided evenly between McCollum and Brown, “will come in soon,” Abrams said. It could be a different story for the $75 million judgment, depending on whether Allen, Snead’s estate and the SBI appeal the verdict. Retroactive interest applied to the verdict, dating to the start of the civil case in 2015, could push the final amount due the brothers past $100 million, and could be a motivating factor in accepting the judgment, Tarlton said.

“That timeline could be short or long depending on whether the defendants want to continue to fight, as they’ve done for 40 years, or if they want to acknowledge that justice was done and step up and do their part,” Abrams said. “At the end of the day, it’s the state of North Carolina, and its own insurers, and the question I would have is, there was a clear and grave injustice.

“The state has the opportunity to continue to fight rectifying that, or it can step up to the plate and make these two citizens whole, as the jury demanded that they do.”

McCollum, 57, and Brown, 53, entered the world four years apart and were once condemned to leave it on the same day. During the first trial in 1984, the state built its case solely on the basis of McCollum and Brown’s confessions. The jury needed 29 minutes to return a guilty verdict, then sentenced the brothers to death. A Robeson County judge ordered their executions to be carried out on December 28, 1984.

Appeals delayed it, and Brown, who entered prison as the state’s youngest death row inmate, was later re-sentenced to life without parole. McCollum remained on death row, becoming North Carolina’s longest-serving death row inmate. Both men feared they would die in prison until 2014, when DNA on a cigarette butt placed a convicted rapist and murderer named Roscoe Artis at the scene of the crime.

In time the brothers’ case became a testament to the cracks in the criminal justice system, and also proof, throughout the past several years, of the long road the wrongly convicted must navigate in attempt to hold law enforcement accountable. In the civil case, the brothers’ attorneys convinced the jury that law enforcement officers coerced McCollum and Brown’s confessions and then covered up the truth for decades.

Those officers, Rose said, “had the keys to Henry and Leon’s prison cells in their hands, the entire time.” Rose had long come to believe “that at any point had they come out and told the truth about what had happened during those confessions, that Henry and Leon would have walked out the door.”

And yet Rose acknowledged that the brothers’ exonerations were “really a miracle, with the existence of biological evidence on a cigarette butt.”

“Had that not been there,” he said, “I think Henry and Leon would still be in prison.”

Instead, they received one of the largest, if not the largest, wrongful conviction judgments in American history. Abrams, one of the brothers’ lawyers, said he spoke with McCollum over the weekend, and “it’s already started, that people are calling them and asking for things.” On the other end of the phone, McCollum had just finished mowing the grass.

He “was excited,” Abrams said, “about the prospect of getting some work done on his house, just maintenance work done on his house that was needed. And maybe some landscaping.”