Explore the historically upside-down world of dance marathons in Depression-era Galveston

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

HOUSTON — Texas author Sarah Bird constructs curious dreamscapes.

We, the readers, linger in them for as long as we can, even after we've finished the last pages of one of her luminescent books.

In her recent novel, "Last Dance on the Starlight Pier," that dream world — sometimes a nightmare — involves Depression-era dance marathons, especially a spectacular one staged at an aging venue raised above the Gulf of Mexico in Galveston.

In an America during the 1930s desperate for any type of distraction, marathon couples, some amateurs, others "horses," or pros, danced until one couple was left standing. They followed enforced rules and took designated breaks, but it was really a matter of how long they could endure their foot-bruising, sleep-deprived time on stage.

The pro dancers took on distinct personalities. Organizers devised false narratives to fit their stars. Audiences lapped it up.

More: 'Unsettled Land': New book on early Texas history describes a scene of utter chaos

Bird's novel pivots on the character of Evie Grace Devlin, a tough Texas survivor haunted by her past as a child vaudeville performer and her youth in the seamy Vinegar Hill district of Houston; anxious as an adult to become useful as a registered nurse; but swept up in the dance marathon craze where not everybody or everything is who or what they seem to be.

Galveston Island during the 1930s was a world apart. This version of "Sin City" was held together by a mob-like family who promoted drinking, gambling and other seaside fun.

I interviewed Bird in Houston as moderator during a book signing at Blue Willow Books, then we followed up by email. (Disclosure: My sister, Valerie Barnes Koehler, owns and operates the store.)

American-Statesman: What drew you to a story about dance marathons in the 1930s?

Sarah Bird: The original inspiration was my mother, Colista McCabe, an Indiana farm girl whose father died of a heart attack at the height of the Great Depression leaving behind a widow and four children.

Collie Mac, as we, her six smart-ass children called her, was such a fabulous storyteller and all-around fun person though that, somehow, she made even surviving those hardest of hard times sound like a grand adventure. I, her pathologically shy daughter, was particularly enthralled by her memories of the time a dance marathon was held at the local Grange Hall.

In her recollection, that dance marathon had been a jolly community gathering, sort of like a cross between a church supper, with everyone bringing snacks to share, and a slumber party where the “lucky kids” got to stay up all night and watch the amazing sight of competitors who not only slept on their feet “like horses” but kept moving.

That rosy vision was at considerable odds with the version of dance marathons I encountered in the unrelievedly grim 1976 movie, “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?” For years, decades, the suspicion nagged at me that this film — as superb a piece of cinema as it is — didn’t tell quite the whole story of dance marathons.

More: Guides at Texas plantation committed to preserving truth of 'a very uncomfortable history'

How true that hunch turned out to be. The first thing I learned was that “They Shoot Horses” was based on a novel by an author who had set out specifically to write the first American existential novel.

You know. Camus. Sartre. That whole madcap bunch of party people. So, from the start, extra grimness was baked in.

I used a wide variety of sources to help me recreate the anthropology of the lost world of the dance marathons: contestant memoirs, newspaper articles, journal articles, dissertations, letters, photo and radio archives. Some surprisingly rich sources were cookbooks, movie fan magazines and the "Cherry Ames, Student Nurse" books.

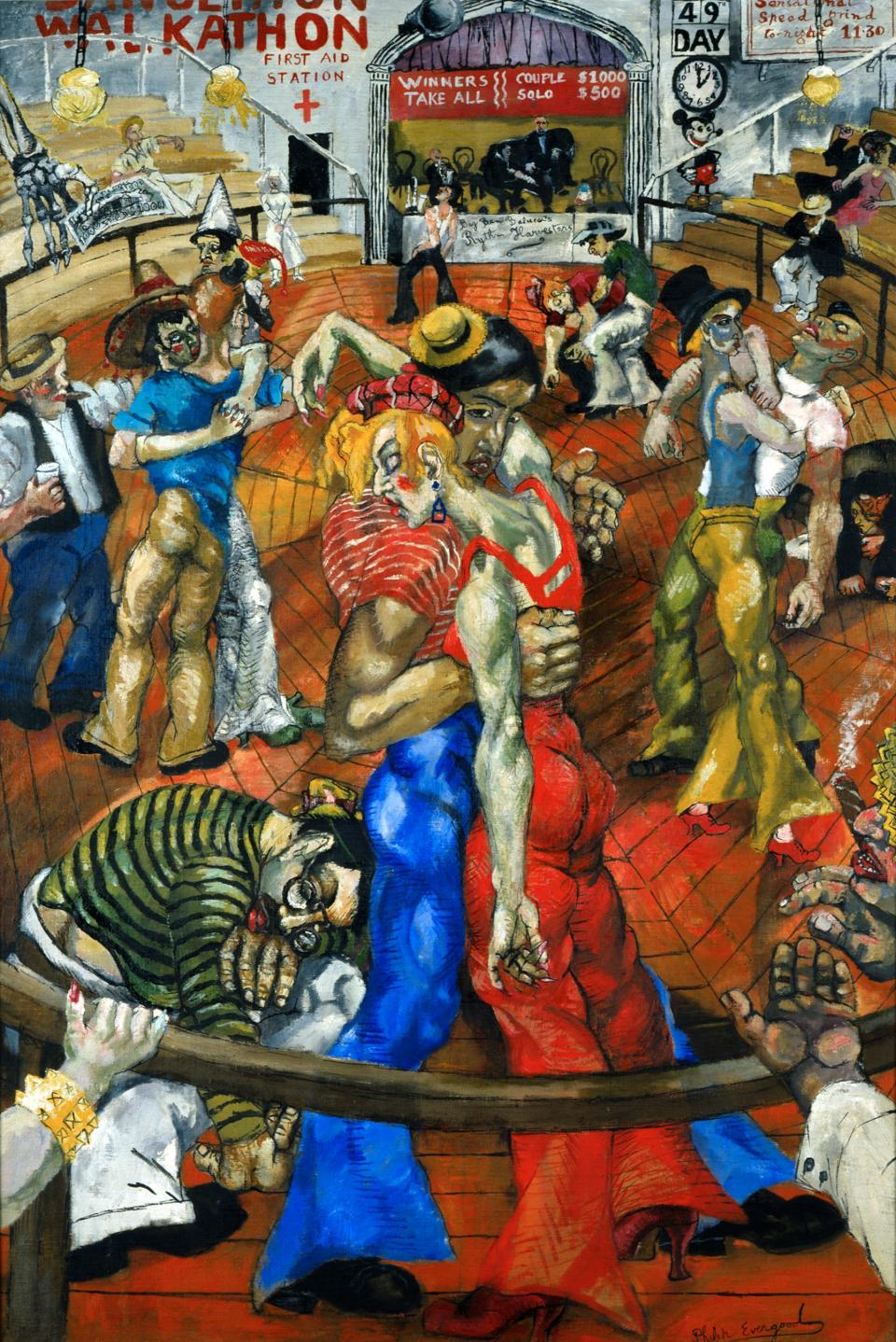

I was also inspired by the finest visual representation of a dance marathon in existence, the painting “Dance Marathon” by Philip Evergood, which we are lucky to have, right here in the Blanton Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

I was quite pleased to learn that, indeed, Hollywood had not told quite the whole story. What cannot be overlooked in any portrayal of dance marathons is how desperate the times were. The competitions were grueling.

But at a time when one quarter of the country was out of work and proud people were quietly dying of malnutrition, they gave contestants someplace warmer than a park bench to sleep and as much food as they could hold.

To the audiences who thronged to these wildly popular shows, they gave a model of hope by performing how, through sheer endurance alone, they might not only survive the endless grind of the Depression, but come out winners themselves.

Your protagonist, Evie Grace Devlin, is a young woman seeking to flee her seamy past in the Vinegar Hill district of Houston by becoming a nurse in Galveston. That raised a historical question: What and where was Vinegar Hill? I had never heard of it.

Vinegar Hill — how could I resist that name? — was, originally, a red light district located south of what is now the Houston Amtrak station. According to local lore the area was named Vinegar Hill either because of an infestation of vinegaroon scorpions or in honor of a particularly fragrant vinegar factory once located there.

In either case, Vinegar Hill represents everything that Evie Grace wants to escape.

The neighborhood and her cast of characters was a favorite subject for Sig Byrd, a 1950s-era columnist for the Houston Chronicle who frequently lamented the passing of this hardscrabble neighborhood and her colorful denizens. Kind of reminiscent of the nostalgia some New Yorkers have for the seedy Times Square of old.

You describe Galveston as a place that the Great Depression passed by. Why was that the case?

Galveston, Texas, in the 1930s is a complete and utter gift to a novelist. I mean, we had our very own "Boardwalk Empire" down here in Texas. Except that the weather was better and the people were nicer.

Galveston back then was possessed of a dark glamour that had been created and was carefully cultivated by a pair of barber brothers, Sam and Rosario Maceo, who had emigrated from, yes, Sicily.

More: History is a click away: The best digital tools for Texas history buffs

The Maceo brothers transformed the city on a sandbar into an international destination for world-class entertainment. High-dollar gambling, top shelf booze and world-class entertainers — Duke Ellington, Phil Harris, Jimmy Dorsey, Peggy Lee.

The Maceos booked them all into their ritzy clubs. Thanks to them, Galveston remained virtually immune to both the dry days of Prohibition and the economic ravages of the Great Depression.

You have said that Galveston is one of the cities in Texas that has kept a strong sense of itself. Talk more about that.

The only city that is as much in love with itself as Austin is Galveston.

I mean, they have their own special acronym for members of the elect who were B.O.I., "born on the island." I’ve lost track of the number of Galvestonians I’ve met who’ve pulled me aside to reveal that they were, indeed, B.O.I.

They always say this with voices modestly lowered as if they were telling me that they are astronauts.

Texas history, delivered to your inbox

Click to sign up for Think, Texas, a newsletter delivered every Tuesday

And their pride is extremely well-founded. Consider this: in 1900 a hurricane — still the worst natural disaster in American history — scraped most of the city right off the sandbar — sandbar! — it was built on.

Did B.O.I.s do the sensible thing and move inland to somewhere with a bit of rock underfoot? They did not. They built a 17-foot high seawall, jacked up what remained of the city, and went on to become Las Vegas before there was Las Vegas.

Take that, Gulf of Mexico!

Several historical incidents come at just the right moments: FDR’s nomination at the Democratic Convention, a dust storm in the Panhandle, the aftermath of Al Capone’s demise in Chicago. Did you know which moments about this period you wanted to use in advance?

I absolutely knew that I wanted to the novel to pivot around FDR winning the Democratic nomination. It was a watershed moment in American history and we’re still feeling the reverberations. In all the important ways, the last election was a replay of the same questions the country was struggling with in 1932.

More: Texas History: The Rio Grande is 'The River That Runs Through Me'

FDR spoke of the injustice of one political party that “sees to it that a favored few are helped” while ignoring the worker. He cautioned against spiraling levels of wealth inequality. He warned of the rise of authoritarianism around the globe and how, just as it does now, these strong-man regimes threaten the survival of democracy.

One of your earlier, smaller books is titled “A Love Letter to Texas Women.” In a sense, “Last Dance on the Starlight Pier” is just such a love letter. Even the unlikable Texas women are portrayed as gritty survivors.

“Unlikable Texas women?” Why, isn’t that an oxymoron?

Seriously, I definitely wanted to celebrate the resilience of Texas women in the novel, particularly the Panhandle heroines who survived the Dust Bowl. I have so many magnificent exemplars among my friends and I canvassed them all when I was writing “Love Letter” on the question of where they believed their unique strength came from.

My favorite answer was the friend who said, “Texas women have to be strong because Texas men are so crazy!”

We certainly are at another historical time when Texas women are required to be strong and rally against the forces seeking to repress us.

After a whirlwind 400 pages of short chapters and frequent plot twists, you tie the action up in a beautiful bow. It works. Why?

The biggest challenge in writing a novel and the one I most aspire to is the “earned” happy, or certainly, satisfying ending. I hope that in creating the genome of my protagonist I planted the DNA of her inevitable, if not triumph, her heroic survival.

The ending is actually fairly bittersweet because Evie Grace doesn’t get everything she dreamed of. By timing the ending to coincide with a genuinely happy moment in American history, the book does end on the note of giddy optimism that swept America when FDR was nominated.

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@statesman.com.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Inside the crazy world of dance marathons in Depression-era Galveston