Explore the history of the Underground Railroad and Trail of Tears this holiday season

Sites commemorating the Underground Railroad and Indigenous American history exist throughout North America. Have you visited one yet?

It’s the holiday season; a time to hopefully connect with family and celebrate another year together. As you sit with parents, grandparents, and maybe even great-grandparents, there is often that trip down memory lane and perhaps even a few family secrets spilled. What if you could stand in that history; walk on a path where ancestors fled to freedom?

Sure, Black History Month will return in February, and Native American History Month (November) is coming to a close. But with Underground Railroad and Indigenous American historic markers, museums, and sites all over North America, your holiday (or other) travels could be an ideal opportunity to take time to get connected to America’s roots — and quite possibly your own. These off-the-beat and independent locations might be closer to home than you think, so check out a few — they might just bring you closer to your own history.

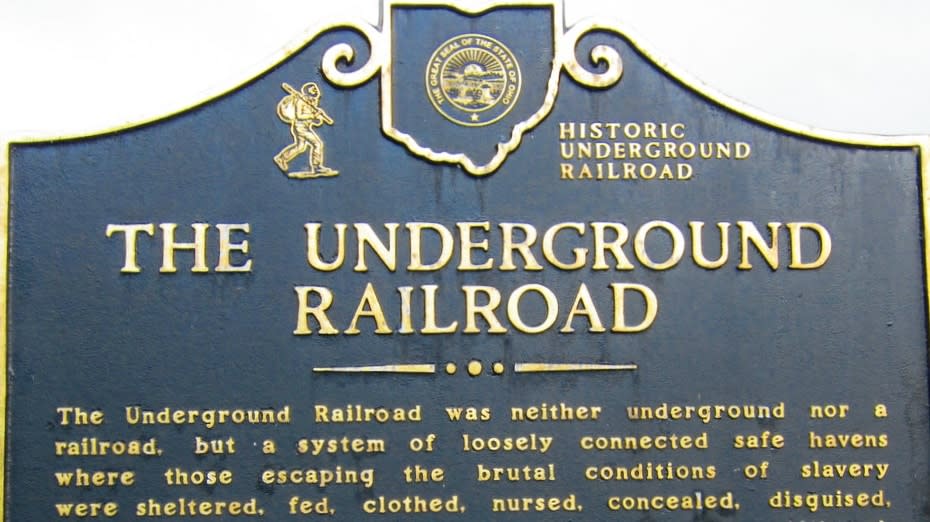

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad extends farther than you think. Enslaved people didn’t just flee from the South to the North. Some fled from the Virgin Islands to Puerto Rico or beyond. Others continued past the Mason-Dixon line and went to Canada, where they could not be returned due to local state laws or The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Many ended up working at sea or on shipping vessels to evade capture.

To trace this history beyond well-known locations like the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in D.C. or the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, the National Park Service created the Network to Freedom with nearly 700 verified Underground Railroad sites in the United States and its territories. Each year, more places are added, making this an ever-expanding journey.

(Photo by Mike Simons/Getty Images)

Fort Christiansvaern Waterfront in the U.S. Virgin Islands

From 1733 to 1848, enslaved Africans were incarcerated and sold at the Caribbean fort. Many resisted and attempted escape. Over 300 freedom seekers made it to Puerto Rico by sea.

Blackburn Rescue and Riots at the Wayne County Jail Site in Detroit

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn escaped from Louisville, Kentucky, and lived in Detroit for two years before they were captured and convicted as runaways under the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act. The jail site where they were held became a hotbed for protests and the couple was eventually rescued and sent across the Detroit River into Canada by Black leaders. The site is now the Rose and Robert Skillman Branch of the Detroit Public Library.

Cozad-Bates House Interpretive Center in Cleveland

The Cozad-Bates House is the only pre-Civil War home that still stands in the area and has been turned into a museum. Neighbors of the Cozads were known to assist freedom seekers including abolitionists, the Ford family.

Downtown Norfolk Waterfront in Norfolk, Virginia

Despite advertisements for runaways, the waterfront was a destination for freedom seekers. Some ships’ captains were known to be sympathetic or would at least look the other way for a fee, transporting people secretly.

Owen Lovejoy House, Princeton, Illinois

Serving as a depot on the Underground Railroad, this U.S. Representative’s home was always open to harbor freedom seekers, who called it and the town the “Lovejoy Line.” Despite prosecution, Lovejoy continued this abolitionist work throughout his life.

Camp Nelson National Monument in Nicholasville, Kentucky

During the Civil War, the Union authorized the creation of the Colored Troops in Kentucky, attracting thousands of freedom seekers to Camp Nelson. By the end of the war, Camp Nelson had emancipated and enlisted 10,000 Black men.

Hotel De Afrique Monument in Hatteras, North Carolina

After Union forces defeated Confederate forces in Hatteras, knowledge of their victory spread. Enslaved people fled to the area seeking refuge, soon establishing the first “contraband” camp in the state. The original locations have since been destroyed due to erosion and flooding; a monument was erected to commemorate their efforts.

Negro Fort in Eastpoint, Florida

Freedom seekers, freedmen, and American Indians made a settlement in Spanish Florida at this British fort. Feeling threatened, Georgia plantation owners petitioned the government to do something. After the British left in 1816, the United States military blew up the settlement.

Chief Vann House in Chatsworth, Georgia

In the 1790s, Cherokee Indian leader James Vann became a wealthy businessman with a plantation covering 1,000 acres. He was known to be cruel; journals of many of those he enslaved document the plantation’s runaways. His family lost the home and plantation in the 1830s when state and federal troops forced the Cherokee Nation west on the Trail of Tears. His two-story brick home still stands today.

Mary Ellen Pleasant Burial Site in Napa, California

Despite being born a freed slave, Mary Ellen Pleasant was still indentured to abolitionist Quakers. She would later become a slave rescuer in New Bedford, Ohio, and New Orleans, fleeing to evade capture in 1852. Pleasant would eventually end up in San Francisco where she became an entrepreneur, real estate maven, and purported self-made millionaire while continuing work as a slave rescuer, becoming known as “the Western Terminus of the Underground Railroad.”

Anthony D. Allen Site in Honolulu

Allen fled slavery at the age of 24 and worked at sea until eventually landing in Hawaii. He became an adviser to King Kamehameha the Great, who gave him six acres of land in Waikīkī on what is now Washington Middle School.

John Freeman Walls Underground Railroad Museum in Ontario, Canada

In 1846, John Freeman Walls fled from North Carolina to Canada where he purchased land from the Refugee Home Society to build a log cabin. This cabin became a terminal stop on the Underground Railroad.

Seminole Indian Scouts Cemetery in Brackettville, Texas

Afro-American Indians fled re-enslavement from Florida to Oklahoma, following the Trail of Tears. Eventually, they went south to Mexico. After the Civil War, they gained a reputation as fierce warriors and were asked to return to Texas to take part in border wars. Consequently, many Afro-Seminole families were buried in this cemetery.

Digital Library of American Slavery

Don’t have time to visit a location? Check out the Digital Library of American Slavery with slave deeds, runaway notices, and petitions collected from throughout the South. These advertisements and court documents tell the stories of thousands of lives, many times nameless, otherwise lost to time.

Indigenous American History

While the best-known Native American museums are located in New York and Washington D.C., there are plenty of historic sites and local museums that cover Indigenous history, migration, and current topics and art.

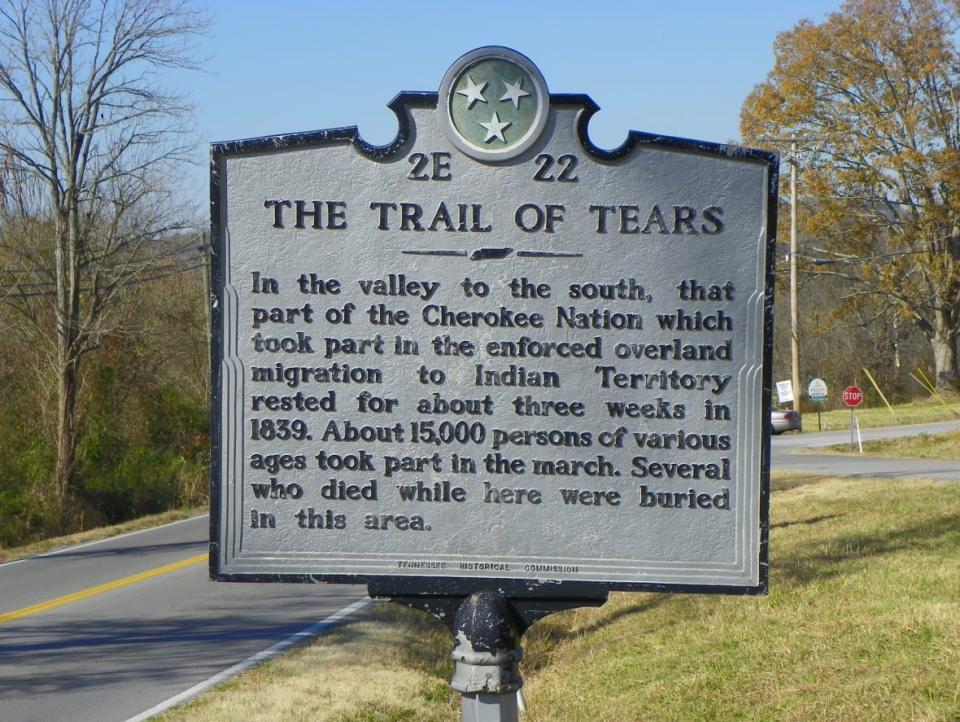

Trail of Tears

The National Park Service has a historic trail that covers the path Indigenous Americans were forced to take on the Trail of Tears through Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

Museum of Native American History in Bentonville, Arkansas

Called MONAH, the museum was launched as a showcase for artifacts but now features Indigenous artists and a lot of informational programming. It is built on the ancestral lands of the Quapaw, Caddo, and Osage peoples.

The Museum of the Southeast American Indian in Pembroke, North Carolina

While the museum does cover prehistory through contemporary American Indian topics, it also focuses on scholarly pieces with an emphasis on the Indigenous communities of North Carolina and of the American Southeast.

Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, New Mexico

This independent museum contains historical and contemporary American Indian art. It also boasts the largest collection of Navajo and Pueblo art in the world.

First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City

This museum celebrates the cultural diversity of Indigenous Americans and recognizes that many of the 39 distinctive Indigenous tribes did not originally live in Oklahoma. Called “FAM” for short, the museum tells a story of resilience through artifacts and programming.

Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre in Whistler, British Columbia

Built on the traditional territories of the Squamish Nation and Lil’wat Nation, the communities came together to create exhibits, tours and programming important to their history and work today.

Museo el Cemi in Jayuya, Puerto Rico

The fish-shaped museum hosts artifacts of the Taíno, the Indigenous people of Puerto Rico. Most artifacts are religious as the word “cemi” means “deity.”

Alutiiq Museum in Kodiak, Alaska

A beautiful little museum in Kodiak that strives to preserve the heritage and living culture of the Alutiiq people, including a repository of artifacts.

Aja Hannah is a writer, traveler, and mama. As secretary of the Society of America Travel Writers: Central States Chapter, she prioritizes travel with an ecotourism or human-first focus. She believes in the Oxford comma, cheap flights, and a daily dose of chocolate.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. TheGrio’s Black Podcast Network is free too. Download theGrio mobile apps today! Listen to ‘Writing Black’ with Maiysha Kai.

The post Explore the history of the Underground Railroad and Trail of Tears this holiday season appeared first on TheGrio.