The ‘Mandela Effect’ describes the false memories many of us share. But why can’t scientists explain it?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

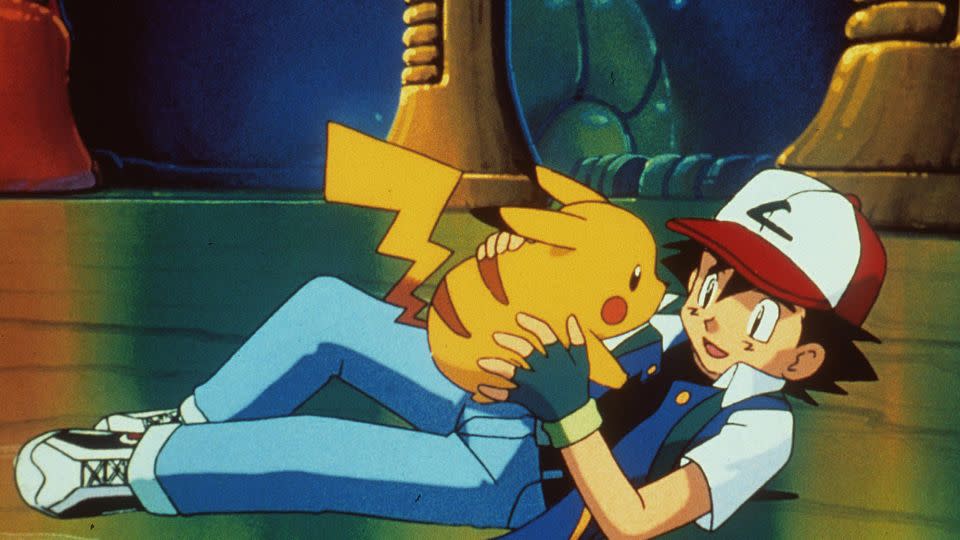

Does Mr. Monopoly wear a monocle? Is there a black stripe on Pikachu’s tail? And does the fruit in the Fruit of the Loom logo pour out of a cornucopia?

If you answered yes to any of these questions — sorry, you’re wrong. But you might also be experiencing the so-called Mandela Effect.

Paranormal researcher Fiona Broome coined the name in 2009 after becoming convinced that then-South African President Nelson Mandela had died in prison in the 1980s. But Mandela did not die in prison; he was released in 1990, went on to lead South Africa and died in 2013. However, Broome noticed that many others seemed to share the same inaccurate memory, prompting further investigation.

Since then, more communal false memories have surfaced, such as C-3PO of “Star Wars” fame being entirely golden (he has a silver leg); Jiffy as the name of a well-known peanut butter brand (it’s just Jif); the spelling of a classic children’s book being “The Berenstein Bears” (it’s really “The Berenstain Bears”); and a host of misquotes from movies, among them “Luke, I am your father” from “The Empire Strikes Back” (the actual line is “No, I am your father”), “If you build it, they will come” from “Field of Dreams” (it’s “If you build it, he will come”) and perhaps the most misremembered of them all, “Mirror, mirror on the wall” from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (the Wicked Queen actually says, “Magic mirror on the wall”).

But why do so many people misremember these?

False memories

“The Mandela Effect is a really fascinating memory phenomenon where everyone seems to show incorrect memories for common popular icons,” said neuroscientist Wilma Bainbridge, an assistant professor in the University of Chicago’s department of psychology. “It is really growing in popularity on the internet on sites like Reddit and TikTok. And while for many people it’s sort of a fun little game that they might play, I realized that it is actually a very interesting effect of human memory that hadn’t been studied experimentally before.”

With coauthor Deepasri Prasad, Bainbridge conducted a rare study published by the journal Psychological Science in late 2022 on the Mandela Effect in which they first confirmed that people have confident, but incorrect, visual memories of famous icons or characters. (Prasad was a lab manager and research assistant at UChicago at the time of the research and is currently a doctoral student of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.)

The researchers tried to find simple causes for the phenomenon, such as people not looking directly at the detail in question when observing the character or images across the internet displaying the errors, but they found no match for these hypotheses. Bainbridge and Prasad also had the participants in the experiment draw the icons from memory to see whether they would spontaneously create these errors, and they found that they often did.

“A big takeaway is that while the Mandela Effect shows up across different types of experiments, there’s no one clear explanation for it,” Bainbridge said, “so future research is needed to see what’s causing this.”

It’s important to remember how prone we can be to inaccuracy, noted Neil Dagnall, a cognitive and parapsychological researcher at Manchester Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom. “Very often when we’re processing information, we see things as we think they are, rather than they actually are. Attention is a very interesting phenomenon,” said Dagnall, who is a reader in applied cognitive psychology.

“With the Mandela Effect, people are often remembering things the way they think they should be rather than they actually are — because we just process things very quickly in everyday life.”

Dagnall brought up the example of the Deese, Roediger and McDermott task, a false memory test in which people receive lists of words to recall: “For example, if we gave people sewing-related items — like pin, cotton, thread — when they are asked to recall them, they also recall words that weren’t in the list, but are associated with sewing, like needle.” In the same way, people could be adding thematically similar details to their recollection of an image, he said.

Ken Drinkwater, a fellow researcher at Manchester Metropolitan, added that the effect might be connected to a condition called false memory syndrome. “In their individual identity and in the way they see the world, people are influenced by factually incorrect recollection. They could strongly believe in something, or strongly believe that they’ve had this experience or this memory, but in actual fact, it’s fantasy,” said Drinkwater, a senior lecturer at the university.

“Several years ago we got to look at whether people could tell between genuine and imagined memories,” Dagnall said. “If you ask people questions about an air disaster, for example, when they recall the events, they wouldn’t just recall what they saw on the news. They would also recall additional information, because they aren’t able to discriminate between what they’d seen — their actual memory — and what they’d imagined. If you think about a plane crash, you can imagine many associated things because you’ve seen them in films, on TV or in the news.”

Some common examples of the Mandela Effect have perhaps logical explanations, such as Mr. Monopoly wearing a monocle because it complements his old-fashioned sartorial style — similar to Mr. Peanut, who has one — or Pikachu having a black tip on his tail because his ears also have black tips. But these generalizations may not apply to other errors.

Parallel worlds?

One peculiar collective memory that demonstrates how powerful false recall can be is of a supposed 1990s movie about a genie called “Shazaam,” starring actor David Adkins, better known as Sinbad. There is no such movie, to the bafflement of countless people on the internet who could have sworn to the contrary.

What does exist, however, is the 1996 movie “Kazaam,” starring Shaquille O’Neal as the title character.

“Advocates of the Mandela Effect think it’s a genuine effect. Many believe this is based on the many worlds or multiverse theory, and that things are different in parallel realities,” Dagnall said, referring to the theory that suggests there may be other universes — potentially an infinite number of them — beyond our own. “I also came across the idea of time travel, which would be causing small changes in the fabric of time.”

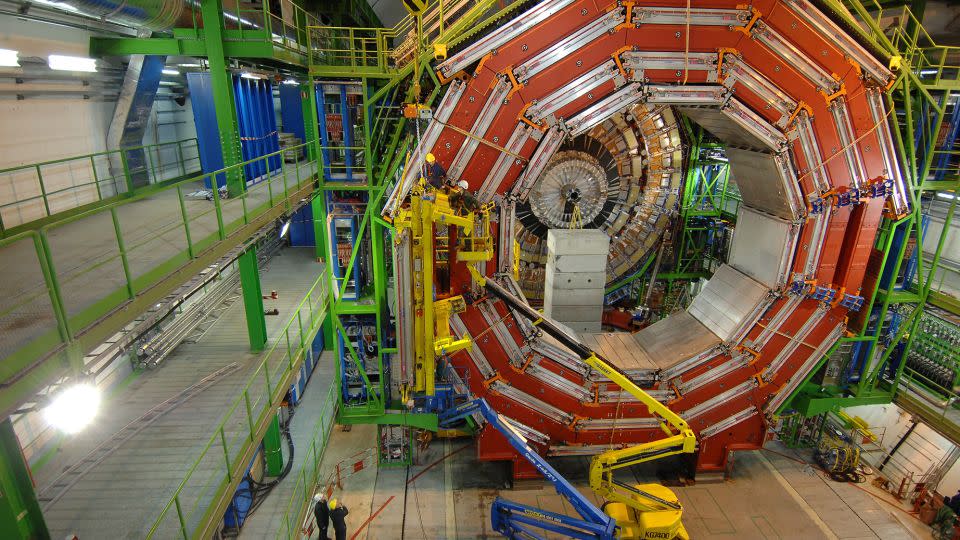

Another popular theory is that the Large Hadron Collider — a particle accelerator at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN, in Switzerland — has opened a portal to a different dimension when it was activated in 2008. Clara Nellist, a CERN particle physicist, responded to such concerns on TikTok — specifically about Oreo “Double Stuf” cookies bearing that name rather than “Double Stuffed” — saying that “there are much higher energy particle collisions happening in our atmosphere all the time. … I can promise you we are not going around changing the labels on your food.”

The lack of evidence to support these theories hasn’t stopped people from getting creative with them. One TikTok account, for example, shows popular Mandela Effect examples through the screen of an early camera phone, which displays the “alternate” version because it is supposedly a technological relic from a parallel universe.

“During times of uncertainty, like the pandemic, disinformation, misinformation and conspiracy theories become more prevalent,” Drinkwater said. “People want to look at something that gives them more meaning. So it could be that belief in the Mandela Effect might be heightened because of this process.”

The University of Chicago’s Bainbridge, however, said she has bad news for alternate reality hopefuls. “Sorry to disappoint people who believe in the parallel universe, but in our drawing study, we asked people if they had heard of Pikachu or Mr. Monopoly before, and if they said no, we would show them a picture. Then, after a short delay, we asked them to draw them from memory,” she said.

“Even those who had never heard of them still made some of these errors, like the tail and the monocle. These people had this false memory right after learning about the characters! Which shows that this effect can happen even without going across parallel dimensions.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com