Exploring north of the Conewago Creek: ‘There are really four York Counties’

(This is another in a series of occasional columns about York County borders and how they helped make York County, York County).

When John Miller presents about "My Roots in the Redland Valley" in September, he’ll be talking about a region that is unfamiliar to many in York County.

And that makes his Sept. 14 presentation all the more important — understanding our collective history is a tie that binds us as a county.

The Red Land region lies north of the Big Conewago Creek, a good part of the northern angle that makes up about one-third of triangle-shaped York County.

Miller lives in an 1884 stone farmhouse built by his great-great-grandfather, his family among the early settlers in the area. He will speak next month as part of a regular series at the Red Land Senior Center in Newberry Township.

Why does the Lewisberry/Newberrytown region seems so remote to many county residents?

York County’s five borders

York County is famously bordered by the Susquehanna River on the east and the Mason-Dixon Line on the south. The rather obscure Beaver Creek helps form some of York County’s western border with Adams County. And the Yellow Breeches, separating much of this northern York County region from Cumberland County, is much better known to many as a recreational waterway than as a border.

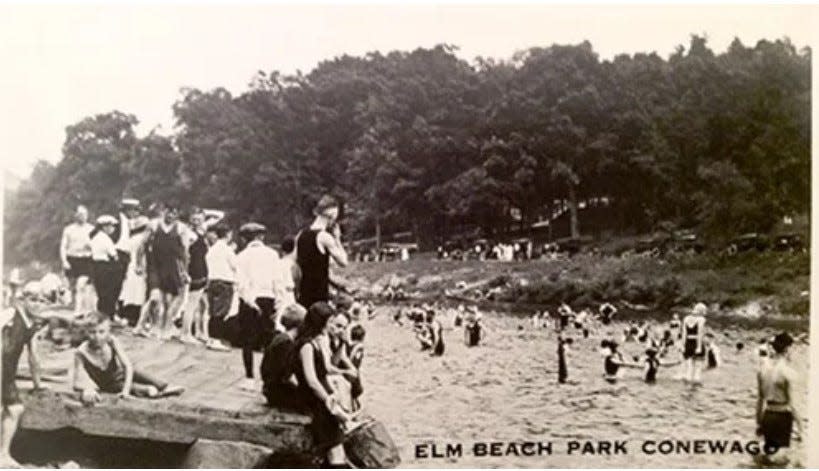

But the county has another boundary to understand: the Big Conewago Creek. Its main branch starts in eastern Franklin County and meanders eastward through Adams and northern York counties before entering the Susquehanna at York Haven.

Above the creek, people generally shop on the West Shore or in Harrisburg. They commute to the Harrisburg area. They went to high school in the West Shore School District, which covers York and Cumberland counties. They go to Harrisburg Senators games and root for Philadelphia sports.

And if they go to the shore, it’s in New Jersey.

South of the Conewago, York County residents are oriented to York or the Hanover area or farther south to Baltimore.

Why does one creek represent such a big divide?

Waterways in the 1700s before bridges represented a barrier to reckon with. Crossing could be tricky with rain swelling fords and making ferry runs unpredictable.

Similarly, York County on the Susquehanna’s west bank developed its own personality, affiliating with Baltimore and points south. Meanwhile, Lancaster leaned toward Philadelphia. Similarly, in York, those living on land west of the Codorus Creek in Bottstown developed apart from the east side of the borough until annexation came in the 1880s.

Those communities north of the Conewago developed their own personality, crossing on the Susquehanna River at Middletown and other Northern ferries. Many other settlers crossed at Wrightsville or other ferries below the Susquehanna River falls in and above York Haven.

Here’s the big thing: The earliest settlers were Religious Society of Friends — English Quakers — pioneers in the Red Land and Fishing Creek valleys and in the Warrington area.

About the same time, the Germans settled below the Conewago and farmed land carved by the Kreutz, Codorus and southern branch of the Conewago. The Scots-Irish put down roots in greatest numbers in the southeastern angle of York County and, with English Catholics, in today’s Adams County.

So, one county and four points of settlement: north of the Conewago, York’s central valley, southeastern York County and Hanover and points west.

The Quakers opened a band of meetinghouses across those northern lands starting in Newberrytown, Lewisberry and Warrington Township outside Wellsville, the latter known today because the Warrington Meeting still worships regularly. The Quakers continued west in York County — today’s Adams County — to form Huntingdon and Menallen meetinghouses in York Springs and Biglerville, respectively.

Think Neapolitan ice cream

The Red Land region took its name from its red sandstone rocks. The late local historian Jim Rudisill would often say you can look at stones used for building and know where you were in York County.

Think Neapolitan ice cream, he would say.

In the southeastern part, stone of a medium brown color was used for construction. In the Kreutz Creek and Codorus valleys extending from Wrightsville to Hanover, builders used white limestone.

The stone of choice in the county's northern part was dark, reddish sandstone, hence its name: Red Land.

Historian Thomas L. Schaefer provided this summary of these English Quaker pioneers: “These settlers found the Redlands soils fairly fertile. The region contained the fine clay pockets for pottery making, too. They also found the local sandstone beds easy to access for building stone.”

The fertility of the red sandstone soil was good enough for the Society of Friends because they brought skills in addition to farming. They operated shops and found kinship with fellow Quakers who led Pennsylvania.

Quaker Ellis Lewis, for example, was a great grandson of Lewisberry’s founder. He embarked on a political career that included terms in the state Legislature, as state attorney general and as state Supreme Court justice in the 1850s.

And Abraham Wells entered into a partnership in the late 1830s to make whips. His brother, John E., joined the business, and the brothers later started a tannery. The borough of Wellsville bears Abraham’s name today.

Diversity north of the Conewago

This northern region served as a crucible for William Penn’s experiment that people of all religious faiths could live together.

So while the English Quakers were the dominant group north of the Conewago, settlers of other Protestant denominations set up camp there, too. The Scots-Irish Presbyterians, for example, founded Dillsburg, a notch in the mountain on the northwest side of that northern angle. They found kinsmen in the Carlisle area, strong-minded Presbyterians who founded Dickinson College.

Methodists founded what became a large congregation in Lewisberry: a group of English origins following former Anglican clergyman John Wesley.

As the years passed, Methodists of a German variety crossed the Conewago and founded congregations. The Paddletown St. Paul’s United Methodist Church is an example of such a congregation.

Church records at Paddletown, some predating the Civil War, are in English. And they show names that are both English and German.

In heavily Pennsylvania Dutch areas of the county, the German language was used in Lutheran worship services until 1890 or later.

German Baptist groups — the Brethren in Christ, for example — founded congregations and, years later, a college just over the county’s northern border, today’s Messiah University.

Another Pennsylvania Dutch congregation founded by an ousted German Reformed pastor in Harrisburg, planted churches spread through the northern region: the Church of God.

York County in the ‘Midlands’

There’s a theory I’ll offer here as another way of assessing this region.

In his 2011 work “America’s Nations,” Colin Woodard divided the country into 11 regional cultures.

York County falls within the “Midlands” region, characterized in history as a “Heartland” culture in which ethnic or ideological purity is not a big deal, a laissez-faire or distrustful view toward government exists and political opinion is moderate, “even apathetic.” This region is marked by swing voting.

Yet just south and west of York County’s border with Maryland, 65 miles before 1800, lies what Woodard calls a “Greater Appalachian” region, peopled by those of Scottish and Scots-Irish descent, accustomed to war and strife in their home regions of Scotland and Northern Ireland. They sought individual liberty, displayed combative natures and enslaved people in greater numbers than the Germans and other groups.

The closer York countians farmed and lived to the Mason-Dixon Line, the more they took on these traits. And the farther away from the border — say north of the Conewago — these Greater Appalachian ideas flowed less freely. These northern York County Quakers saw things differently, eschewing slavery, holding to pacifism and providing help to freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad.

These differences became manifest in the 1860 presidential election. Voters in this northern region backed Abraham Lincoln for the presidency when much of the rest of York County voted for Democratic candidates, particularly supporting John Breckenridge, the preferred candidate in the South. Voters in five of the seven townships north of the Conewago backed Lincoln.

You could say beliefs, distance and the width of a creek from the Mason-Dixon Line made these northern York countians different.

Thinking, acting regionally

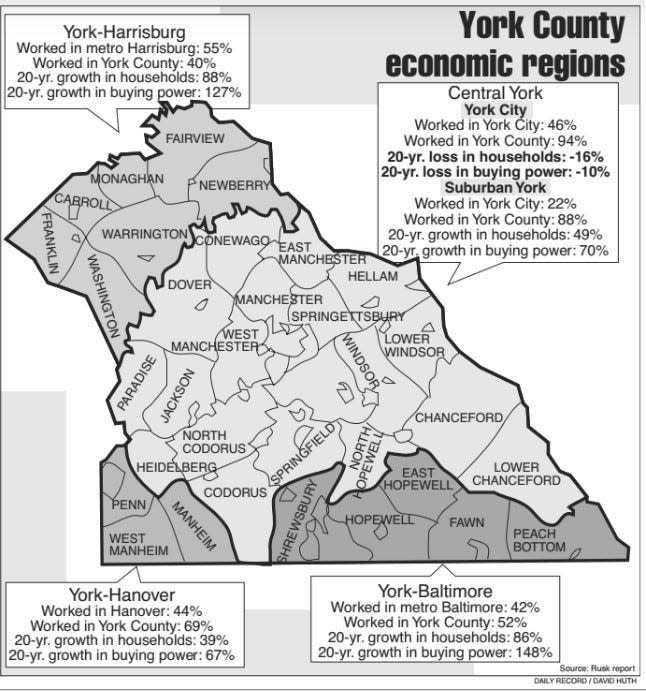

In his three socioeconomic reports about York County between 1996 and 2019, urban planner David Rusk clearly saw the northern region as a land unto itself.

“There are really four York counties,” he wrote in 2002.

In fact, his modern assessment divides the county into roughly the same four regions as reflected in past patterns of settlement.

In looking at commuters, he noted that in 1990, more residents in the northern region drove to work in the Harrisburg area — 55% — than commuted to work in York County — 40%.

The three other areas of commute: York-Baltimore, York-Hanover and Central York are somewhere in the rear. The point is that the Central York area provided the jobs for decades but has increasingly become a land of bedrooms.

“If this was a harness race at the York County fair, York-Harrisburg, a powerful stallion that is part of the governor's stable, would be stepping smartly toward the finish line, lengthening its lead with each furlong …,” Rusk wrote about those living north of the Conewago.

Some might argue that these four York counties shows diversity and thus the ability of a county to better adapt.

But a strong counterargument — one that Rusk consistently makes — is that in today’s complex world, it’s necessary to think and act regionally.

For example, Rusk argues in his three reports that the containment of sprawl and its impact on the agricultural, economic and overall quality of life is a countywide responsibility, one impaired by four regions going their own ways.

Explaining region to others

Given all this history, the good idea of increasing understanding among York County’s regions is daunting.

In the past five years, some groups have been fighting the good fight in telling the northern region’s story to the rest of York County.

John Miller’s scheduled explainer of the Red Land region is one example. Preserving the History of Newberrytown and the Goldsboro Historical Association operate active Facebook groups. The North Eastern York County History in Preservation group sponsors regular presentations at the Red Land Community Library and offers a website with historical information from both sides of the Conewago.

I will present about “Fascinating Things about Northern York County” to an OLLI at Penn State York class this fall.

The Newberrytown-based streaming/YouTube series “Hometown History, which I help produce, covers topics on both sides of the Conewago.

And planners of the York County History Center’s new museum in York’s old Met Ed steam plant are working to tell the story of all corners of the county including this land north of the Conewago.

In the northwest corner, the Dillsburg-based Northern York County Historical & Preservation Society — NYCHAPS — is one of the county’s most robust history groups.

Interestingly, this organization, centered around a tavern built by the town’s founding Scots-Irish family, has embarked on a project to construct a distillery on its grounds. This points back to the day that most York County farmers — of all nationalities — operated stills.

“As the state’s first Distillery of Historic Significance, NYCHAPS will show how whiskey and freedom intertwined,” the group’s website states.

The project, based on plans of an early Pennsylvania distillery, will be called Eichelberger Distillery at Dill’s Tavern.

When the distillery is completed, a unity that at times has escaped York County since its founding will be displayed in its northwestern tip.

A distillery of German design will be operating on land settled by Scots-Irish in a region where English Quakers originally dominated.

Sources: Thomas L. Schaefer’s “Patterns of Our Past,” northernyorkhistorical.org, Colin Woodard’s “American Nations,” George Prowell’s “History of York County,” James McClure’s “Never to be Forgotten,” YDR files.

More: Rusk reports 1, 2 and 3

Upcoming presentations

I will present on these three topics in the fall term at OLLI at Penn State York:

“Fascinating Things about Northern York County,“ “When Ephrata's Cloister Opened a Branch Campus along York County's Bermudian Creek” and “When Diplomat George Kennan and Other Famous People Viewed Adams County's East Berlin and Its Region as Home.” Details: olli.psu.edu/york/courses.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Exploring north of the Conewago: ‘There are really 4 York Counties’