Exterior of Harriet Beecher Stowe House restored, interior work under way

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The grand yellow house at the corner of Martin Luther King Drive and Gilbert Avenue in Cincinnati has been home to many over its 191-year life.

But the months that Harriet Beecher Stowe lived at the address in the city's Walnut Hills neighborhood earned the house its name, its fame and a $4.5 million renovation that began in 2016.

“It’ll be a couple of years before it’s all done,” Christina Hartlieb, executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House said during a May tour, just days before a short closure for renovation work.

In June, workers were scheduled to rebuild fireplaces and their mantles, fix floors and remove parts of the second-floor ceilings in the 5,000-square-foot home. A new heating and cooling system was to follow.

Exterior renovations are largely done, with 17 layers of paint removed and the original yellow reapplied. Gone are a front porch, a two-story bay window and a fire escape. Installed were 44 windows, 20 pairs of shutters and doorways that replicate the originals.

Once interior work is complete – by spring of 2025 – some rooms of the house will evoke the 1840s, when Beecher family members were residents, and some will resemble the 1940s, when it operated as the Edgemont Inn boarding home and tavern for Black residents.

Depicting that dual history will require some sleight-of-hand decorating. One example: Visitors to 1840s rooms will see depictions of outdoor scenes through some windows since the views are actually blocked by 1940s construction.

Given the home’s place in African American history, keepers of the home wanted to showcase the Edgemont years (1930s and 1940s) along with the Beecher years (1832-1851).

“We didn’t want to erase that history,” said Hartlieb, the sole full-time employee of home manager Friends of Harriet Beecher Stowe House.

Still, the author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” remains the star of the home and the primary draw for some 5,000 visitors a year. She lived there, on and off, during the early years of her 18-year stay in Cincinnati, mostly between 1833 and her marriage in 1836.

Stowe penned the most famous of her 30 books in Maine, after leaving Cincinnati in 1850 when husband Calvin Stowe signed on to teach at Bowdoin College. Aggrieved by laws that criminalized helping fugitive enslaved persons and angered by what she’d learned about slavery during her Ohio years, Stowe tells the story of what happens to a middle-aged enslaved man named Tom when a Kentucky farmer sells him to a slave trader.

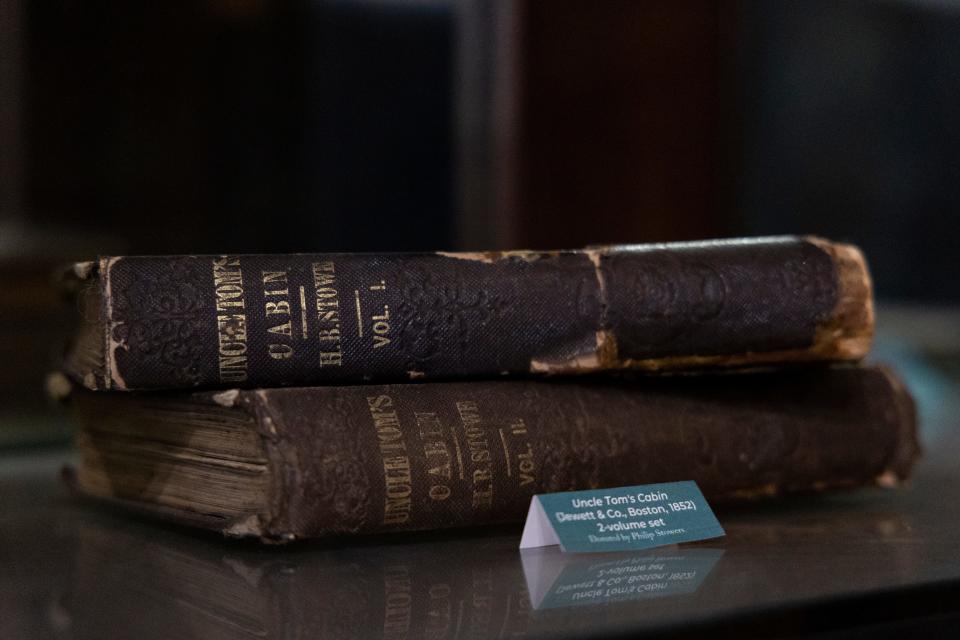

The book – originally published as a 40-week serial in an abolitionist paper called “The National Era” – was an instant success when published in 1852. In short order it became the best-selling title in the United States, behind The Bible, and was translated into 20 languages.

Despite criticism in later years for fomenting negative stereotypes about Black Americans with excessive melodrama and religiosity, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” retains its reputation as an influential classic in U.S. protest literature.

A visit to the Harriet Beecher Stowe House offers other glimpses into Stowe and her family of origin.

What does the house look like?

Entering from Gilbert through the front door, Lyman Beecher’s study sits to the right and the family parlor to the left.

Lyman Beecher, an outspoken Presbyterian preacher, brought his family to Cincinnati from Boston to become the first president of the new Lane Theological Seminary. He welcomed students and faculty into both front rooms, according to Hartlieb.

In 1834, the school lost many of those students after they participated in 18 days of robust debate over slavery and school trustees then banned discussion of controversial topics. A young Harriet Beecher, just 21 when her family came to town, first learned about slavery during the famous debates.

The original home was L-shaped, with a dining room and kitchen wing off the parlor and bedrooms on the second floor. In the next century, the home was remade into a solid rectangle for the boarding house and tavern.

Who was part of the Beecher family of origin?

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher was born in Connecticut in 1811, one of 13 children of Lyman Beecher. Lyman’s first wife, Roxana Foote, was mother to nine, including Harriet. When Roxana died, he had four more children with his second wife, Harriet Porter. He married again, to Lydia Beals, when his second wife died but had no additional children.

Nine of the 13 Beecher children were writers. Older sister Catharine Beecher was a noted educator, brother Henry Beecher was a famous preacher and abolitionist, and brothers Charles Beecher and Edward Beecher were also accomplished ministers.

What about the Stowe family?

In 1836, Harriet Beecher married widower Calvin Stowe, who taught biblical literature at Lane Seminary. Later that year, she gave birth to twin daughters Harriet (“Hattie”) and Eliza in the house that now bears her name.

The Stowes welcomed five more children in the next 12 years: Henry in 1838, Frederick in 1840, Georgiana in 1843, Samuel in 1848 and Charles in 1850. Harriet Beecher Stowe outlived four of them. Losing son Samuel to cholera at age 18 months gave her empathy for mothers who lost children to slavery, according to histories of her life.

What about her later years?

The Stowes spent winters near Jacksonville, Florida, beginning in the late 1860s, believing the state had fewer racial divisions than the rest of the South following the Civil War.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was active in Florida’s new tourism industry there, writing about the natural beauty of the state for readers in the North. Steamship companies that brought tourists down the St. John’s River paid her to wave to passengers from her front porch, according to the Florida Historical Society.

Back in Connecticut, Stowe was among the founders of the Hartford Art School, which later became part of the University of Hartford.

Stowe’s health declined after the death of her husband in 1886. Battling dementia, she started writing “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” over again, not recalling she’d already published the work, according to news reports at the time.

Harriet Beecher Stowe died July 1, 1896, and is buried at Phillips Academy in Hanover, Massachusetts, alongside husband Calvin and son Henry.

Where can you learn more?

The Florida Historical Society reports on the Stowes’ time near Jacksonville.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford provides links to original newspaper publications of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati offers links and videos about its namesake resident and the home itself.

The Walnut Hills landmark is generally open for tours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Thursdays-Saturdays and noon to 4 p.m. Sundays. Check the website or call 513-751-0651 to check on any construction interruptions.

Admission is $6 for adults, $5 for seniors and college students, and $3 for children aged 3 to 18.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Where is the Harriet Beecher Stowe house?