Extreme heat kills and maims. Here are some of its victims from across the US.

Florencio Gueta Vargas' wife made sure he had snacks and plenty of water that summer morning. “Take care,” she told him as he left to work at a Washington state hops farm. Hours later, a family member found Vargas' empty pickup truck.

About 2,000 miles away in Louisiana, Tina Perritt sat on her porch, eating a BLT and enjoying a cold drink. It had been more than four days since a tornado knocked out her power, leaving her sweltering. But Perritt wasn't leaving home.

In Texas, Jared Farley clung again to a cellphone tower 300 feet above ground. That June day the heat index soared to over 100 degrees. He doesn't remember passing out.

Across the country, one form of weather kills more Americans, on average, than any other event − deadlier than floods, tornadoes, wind storms, or hurricanes.

The killer is heat. Often it kills quietly, striking people without air conditioning, people who live on the street, and people who labor in outdoor jobs. And because it kills individually, rather than in a single spectacular flood or storm or debris field, its victims have often gone ignored.

Focus on extreme heat is rising as the climate changes. July was the hottest month in the planet's recorded history. Phoenix logged a record stretch of 32 days above 110 degrees.

But the increased concern may point out a stark reality. This year's heat wave has made America more aware of heat deaths. But in spite of greater awareness, the numbers are likely to keep rising.

"The scary part is this summer may be one of the coolest summers we'll experience in the next 50 years," said Michael Webber, a professor of energy resources at the University of Texas at Austin. "I don't think we're prepared for that."

To try to understand the true toll of extreme heat, USA TODAY reporters interviewed families like Vargas' and Perritt's whose deaths were attributed to high temperatures and people like Farley, who survived, but whose lives were transformed by particularly hot days.

Every day of extreme heat in the United States claims about 154 lives, according to a 2022 study, and this summer has had more than its share of warmth.

Meanwhile, certain people are at greater risk.

Extreme heat affects people differently, that 2022 study found. Men are more likely to die on hot days than women; Black adults more than white ones; residents of cities more than those in rural areas. People 65 and older make up over half of the estimated deaths associated with days that are unusually warm.

Jobs make a difference too. Farmworkers are 35 times more likely to die a heat-related death than the average American employee. And construction workers have the next highest risk at 13 times the average, according to a 2016 review of labor data.

But heat can kill and injure people of all ages and professions, striking the healthy as well as the vulnerable.

Below, USA TODAY tells the stories of six heat victims.

SAFETY TIPS: Excessive heat really is dangerous. Here's what doctors want you to know.

Gwendolyn E. Osborne: Author who died in a sweltering Chicago apartment

Gwendolyn E. Osborne, a hopeless romantic, book reviewer and journalist, spent much of her life championing the work of other Black writers, especially those who wrote Black romance novels.

“She helped give credibility to the whole genre,” her son Ken Rye told USA TODAY.

She died at age 72, sweltering in her apartment in a Chicago senior living facility, where temperatures reached more than 100 degrees during a May 2022 heat wave.

A founding member of the National Association of Black Journalists-Chicago Chapter, she earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Michigan State University and a master’s at Northwestern. Rye said his mother had worked in public affairs for the University of Illinois-Chicago and the Chicago-Kent College of Law and was active in the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

“She was mind-blowing,” he said. “She was known nationally and internationally.”

Osborne had chosen a strategic location for retirement living, with easy access to shopping and transportation, and had lived there several years, he said.

But that May, temperatures in Chicago had been at record highs of 89 or above for several days – averaging more than 20 degrees above normal. A law firm representing her family, Levin & Perconti, has stated the building’s air conditioning hadn’t been turned on.

Osborne and two other women, Janice Reed and Delores McNeely, were found unresponsive in their apartments.

Without air conditioning, experts say warm overnight temperatures that don’t give people a chance to cool down can be particularly deadly during heat waves.

“Climate change is a factual reality," Rye said. “There’s got to be better protection for our seniors.”

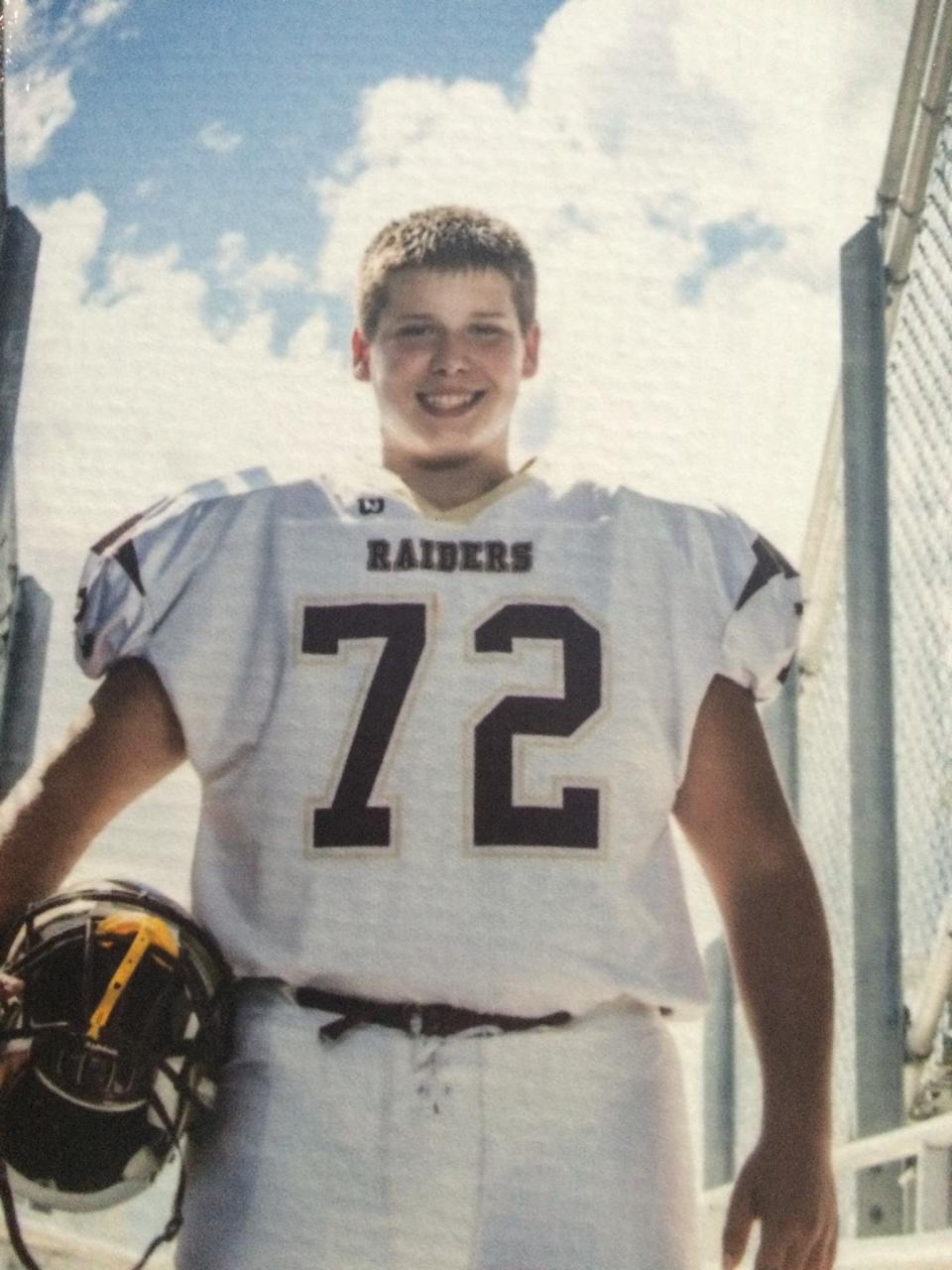

Zach Martin: Teen athlete who died after collapsing at football practice

June 29, 2017, was another typically hot day in southwest Florida, Laurie Martin Giordano remembers. The high temperature was 92 degrees in Fort Myers, with the typical high humidity.

It didn't have to be unusually hot to endanger her son, 16-year-old son Zach Martin – a strong, 6-foot-4, 320-pound high school football player.

He was a “gentle giant,” Giordano told USA TODAY. Zach was always smiling, always seeing the humor in things, she said.

On that late June day, Zach had just finished running sprints with the Riverdale High School football team when he collapsed. He was taken to Golisano Children's Hospital in Fort Myers, where they diagnosed him with a core temperature of 107 degrees, exertional heat stroke, devastating internal injuries and a coma.

He was moved to Holtz Children's Hospital in Miami six days later for more specialized care. Zach's condition continued to worsen, and he was removed from life support 11 days after he collapsed, with the official cause of death reported as exertional heat stroke.

In the six years since her son’s death that summer, Giordano has become an activist, spreading awareness about exertional heat stroke and what can be done to ensure there are no more deaths because of it.

She has created the Zach Martin Memorial Foundation as a tribute to the memory of Zach and also to be sure no other parent has to endure what she went through.

“Exertional heat stroke is preventable and survivable with some precautions,” Giordano said. An ice-filled tub is incredibly effective.

When saving someone from heat stroke, it's "the sooner the better,” she said.

HOW TO STAY SAFE: Staying cool during hot weather

Jared Farley: Cellphone tower worker left with injuries from heat

Jared Farley, 31, used to love hunting, fishing and riding dirt bikes.

Now, months after he passed out on the job in scorching heat, he struggles to be active for more than 30 minutes.

On June 15, Farley was working 300 feet in the air servicing a cellphone tower in Navasota, Texas, when he suddenly passed out, according to his mother, Tracy Phifer.

Farley had been working on the cell tower since 9 a.m.; Navasota Fire Department officials responded to the emergency call at 4:30 p.m. Although temperatures registered 98 degrees Fahrenheit that afternoon, Phifer said the heat index (or what the temperature feels like to the human body) was closer to 110 degrees.

It took about three hours for emergency services to safely bring Farley down from the tower using a rope rescue system, according to reports. Phifer said they performed three rounds of CPR to revive him before rushing him to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Bryan, Texas.

Phifer received the emergency call at her home in Springville, Tennessee. She was told by the head nurse her son was the most critical patient at the hospital.

After driving 11 hours, Farley's mother arrived at the hospital to see her son in the intensive care unit on life support. The doctors were unsure how long Farley’s brain had gone without oxygen, and they didn’t know if he was going to wake up or be able to speak again.

But Phifer had hope.

“Jared has always been a fighter,” she said. “He fights for everything that he has in life.”

After a week on life support, he woke up.

“Hi, momma," he weakly said after the tubes came out of his throat.

“As a mom, it was everything I could have hoped for,” Phifer said.

The hospital discharged Farley on June 27, and his mother took him to Tennessee. Once they got settled, Phifer realized it was going to be a long road to recovery.

Farley can’t leave the house for more than a half-hour without needing to return home to rest. He still has trouble walking straight and has problems with his short memory. He doesn’t remember the incident.

Javier Silva: 'My body felt like it was shutting down' after working outdoors in Florida

Concrete worker Javier Silva, 25, said he started throwing up and cramping after a day of work when the temperature hit 93 on a Florida job site in April.

“It was hot, very hot,” he said in Spanish via a translator. “When I started to feel sick my body felt like it was shutting down, cramps everywhere down my body, I started to throw up profusely. It was hard to even form coherent sentences.”

His supervisor insisted he go inside to a cool break room, and Silva ultimately went to the hospital where he stayed 24 hours getting rehydrated with IV fluids. He said he’s fully recovered now.

Silva said he knew heat could be dangerous, and was wearing a long-sleeve shirt and pants to protect himself from the sun. He said he’s now more aware of the importance of staying hydrated during hot days – and is trying to get out of concrete work after about five years.

He said people driving past in air-conditioned cars don’t really understand what it’s like to work in the heat. And he wishes more people would offer workers water.

"You never know when someone is on the brink of passing out."

Tina Perritt: Family mourns mother who died in house without power

Tina Perritt, 62, was a “little feisty woman” with a huge smile whose friends and family called a fire cat. She loved her family, her grand- and great-grandchildren and “Stevie Nicks and anything from Fleetwood Mac,” said her daughter Tina Patrick.

“When my mom loved you, she loved hard,” she said.

The Louisiana native had an untamed streak and delighted in classic rock concerts. In February, when the 1970s bands Journey and Toto played near their home in Keithville, Louisiana, Patrick went to the show and FaceTimed her mom.

“She was so happy. She was sitting there at home just singing away with it.”

On Friday, June 16, a tornado hit their tiny town, knocking out power to both Patrick and her mother.

There was still water, so she could take cold showers but Perritt’s phone was out and there was no cell service.

Temperatures those five days were in the high 90s and once hit 100. “There’s no telling how it was inside the house,” Patrick said.

Someone from the family came in every day to check on Perritt but she was determined to stay put.

On Saturday Patrick’s family made the two-hour drive to Lufkin, Texas to buy a generator. Her power finally came back on Monday but her mom’s was still out. Tuesday after work she took her mom a BLT and some cold drinks. They sat on the porch and Patrick tried to get her mother to come stay with her.

Perritt said she was “miserable” with the heat but at night it was better. ‘I’ll be fine. It’s dark now, it will be cooler,’” she told her daughter.

The next morning, Patrick’s sister’s boyfriend drove over to the house to bring Perritt the generator.

“They found her on the bed,” her daughter said. The extreme heat had killed her.

The next day, the power came back on.

“Mama’s missed every day,” Patrick said. “It’s still hard not to pick up that phone.”

Florencio Gueta Vargas: Farm worker, father 'never got to meet a grandkid'

Father to six daughters, Florencio Gueta Vargas’ life revolved around his home and his farm work.

Born into a farming family in Mexico, Vargas moved to the United States in his mid-20s and followed the harvest seasons, picking oranges and almonds in California and then hops and cherries in Washington state.

He settled in Wapato, Washington, 2½ hours southwest of Seattle, when he married and worked the rest of his life in fields of hops. Occasionally, he’d enjoy the product of that work, grabbing a six-pack on the way home, and drinking one or two on the porch, before going inside to cook dinner.

“For my dad, there was no sick day. It was just work, work, work,” said Lorena Cortez González, the oldest of his daughters, now 31.

Although his children could see the exhaustion etched on his face, Vargas never complained. Co-workers told them he made work fun with his constant joking and teasing.

As they got older, the girls realized how hard their father was working under difficult conditions. Sometimes bringing him lunch in the field, they would grumble about having to stand out in the suffocating heat while he ate his hamburger. The 10-foot-tall hops plants trapped warmth and humidity and made it hard to breathe just standing still, González said.

“He would tease and say ‘I love the heat. The hotter the better.’ ‘Dad, you’re crazy,’” his daughters would reply.

On the morning of July 29, 2021, González said her mother, Maria Guadalupe González, walked Vargas to his car, which she didn’t typically do. She made sure he had his cooler, snacks and plenty of water. “Take care,” she told him.

Around 3 p.m. a cousin called to say Vargas’ empty truck was still in the farm’s parking lot, but the workers had been sent home hours earlier because of the heat.

The family converged on the farm office to figure out what was going on. A little after 4, the farm owner drove up with a local sheriff. Vargas, 69, who had no major health problems except gout and cataracts, had died on his tractor.

Lorena González is still not entirely sure what happened, but she thinks he was trying to dig the tractor out of a muddy spot and was overcome with heat stroke. He wasn’t discovered in time.

She remembers checking her phone that afternoon and seeing a triple-digit temperature. It was probably 15 degrees warmer in those fields, she said.

A few tents and water stations. A first-aid class to help workers identify signs of heat stroke. Walkie-talkies to enable supervisors to check up on workers, particularly before leaving for the day. That would have been enough to save Vargas’ life, González said.

Just this summer, permanent rules took effect statewide in Washington requiring workers to be provided with cool water and shade when temperatures top 80. Above 90, they must get paid rest breaks of 10 minutes every 2 hours and over 100, 15 minutes every hour. A buddy system, radios, or telephones have to be offered if temperatures spike 10 degrees above the average of the previous five days, according to the new rules.

Vargas’ death devastated the family.

Maria Guadalupe González, who had stayed home to care for their two youngest daughters, both of whom have health issues, went back to work to support them. Always in pain from a bad shoulder, she now works full time at a warehouse.

As the oldest, González feels she has to hold everything and everyone together. But she admits it isn’t easy. She contemplated suicide after her father’s death.

Good days now outnumber the bad, but it’s hit 98 a few times recently and the high heat triggers memories. “It just all comes back to you,” she said.

A certified nursing assistant in a nursing home, González cares for people her father’s age and older every day. She feels guilty she couldn’t save him and watches sadly as they enjoy the old age he was denied.

“We were just so young when Dad left,” she said, crying. “He never got to meet a grandkid. He didn’t get a chance to walk any of us down an aisle … We just felt like it shouldn’t have happened.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Excessive heat victims' stories reveal tragic toll of injury, death