An eye-opening experience: With high-tech help, visually impaired kids see world anew

Nyla Wallace has coped with vision challenges for most of her 16 years, but was only recently diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, which causes an individual’s sight to deteriorate over time and has no cure.

Even more recently, she was given something that will — finally — give her some relief from her ailment.

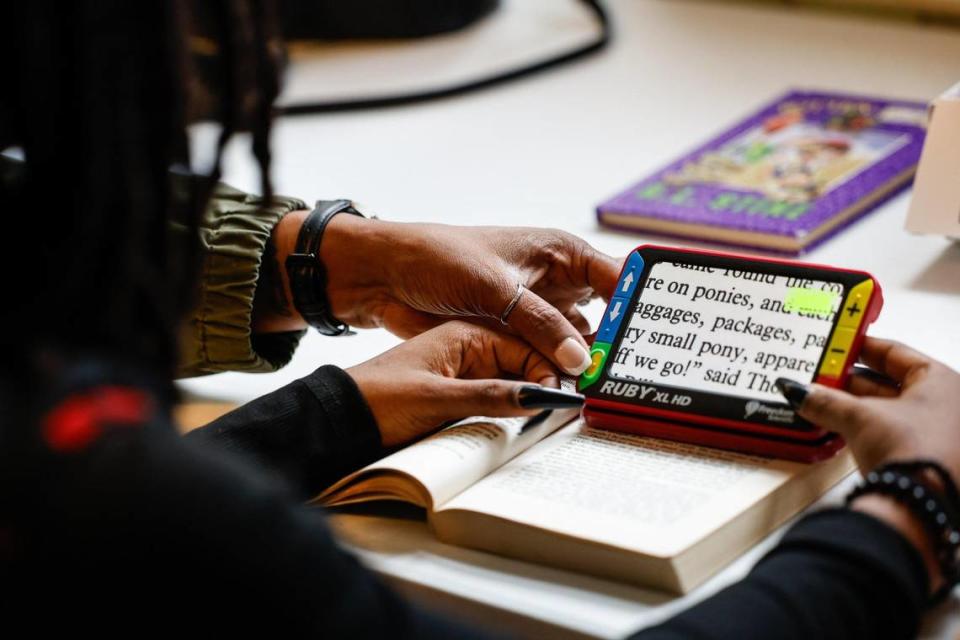

On Thursday, the Mallard Creek High School sophomore received a $1,000 Ruby XL HD handheld device capable of magnifying materials up to 14 times and casting the image onto a five-inch screen, with options for tweaking the colors and the contrast in a way that will make words and details pop for her.

Her mother, Robyn Wallace, wishes they could have gotten their hands on such a thing years ago.

“It’s been a bit of a struggle with her, academically,” she said of Nyla two days earlier, while they sat together in the living room of the family’s home in north Charlotte. “And I do feel like quite a bit of it is because of her struggles with seeing, and … I feel like maybe Nyla didn’t know how to articulate that. Because we would just get onto her and say, ‘Why didn’t you turn this assignment in?,’ and she would say, ‘I work really slow.’ She never did say, ‘I can’t see,’ or ‘When I’m reading, I lose my place and I have to start back over, so it just takes me a long time.’ She never said those things.

“So, we had no idea.”

But they do now, and on Thursday Nyla was among 15 blind or visually impaired school-age N.C. children who were trained on and given assistive equipment ranging from low-tech monoculars and dome magnifiers to high-tech portable desktop magnifiers — all of which provide a closer, clearer view of textbooks, food labels, clothing tags, medication stickers, restaurant menus, and more.

Training was led by staffers from Sight Savers America, an Alabama-based non-profit that works to identify and secure the eye-care needs of children and had set up shop for the day at First Presbyterian Church in Concord.

Funding for the equipment — some of which can cost upwards of $4,000 and isn’t covered by insurance nor provided by schools for home use — was provided by The Cannon Foundation, The Mariam and Robert Hayes Charitable Trust, and Vispero. Gift were tailored to each child’s specific needs per evaluations conducted by N.C.-based IFB Solutions’ Community Low Vision Centers.

And as Nyla and her mom were in an adjacent room in the church being trained on the Ruby XL HD on Thursday, Dawn DeCarlo, CEO of Sight Savers America and herself an optometrist, explained that the type of struggle Robyn had mentioned isn’t unusual.

“Think about it: If you were asked to read your homework, and all the print was the size of the print in a phone book, how fast would you fatigue and want to give up on your homework? Fast. You fatigue and you want to give up, you take a break. Then you come back to it, you fatigue, you give up, and you come back. So your homework now stretches through the whole night instead of sitting down and knocking it out and then you go and you play games with your siblings.”

A few minutes later, mother and daughter emerge from their orientation session smiling.

“It’s an amazing device,” Robyn Wallace says after thanking DeCarlo. “It really is.”

“Yes, it’s so handy,” DeCarlo says. “I mean, when you’re going through your laundry and you’re like, ‘Can I throw this in the dryer or not?’ You can read the tags with it. You can bake a cake without saying, ‘Mom, how much vanilla do I need to put in here?’ All of these things that you might have asked somebody for help for in the past, now you’re going to be like, ‘I got this.’”

Nyla smiles again as she tugs at the strap of the carrying case for the Ruby, which is hanging from her shoulder.

It’s 8:45 a.m. She’s off to school from here, and her fancy new magnifier is going with her.

‘Do you want to see something cool?’

That afternoon, Juan Juarez Reyes, 9, and Selena Juarez Reyes, 13, enter the Sight Savers America’s makeshift orientation center with their mother, Andrea Reyes of Albemarle.

Both Juan and Selena are afflicted with a rare genetic eye disorder called Stargardt disease, another progressive and currently untreatable condition characterized by fatty material that builds up on the part of the retina needed for sharp eyesight. Both kids have colorblindness and hazy spots in the center of their vision.

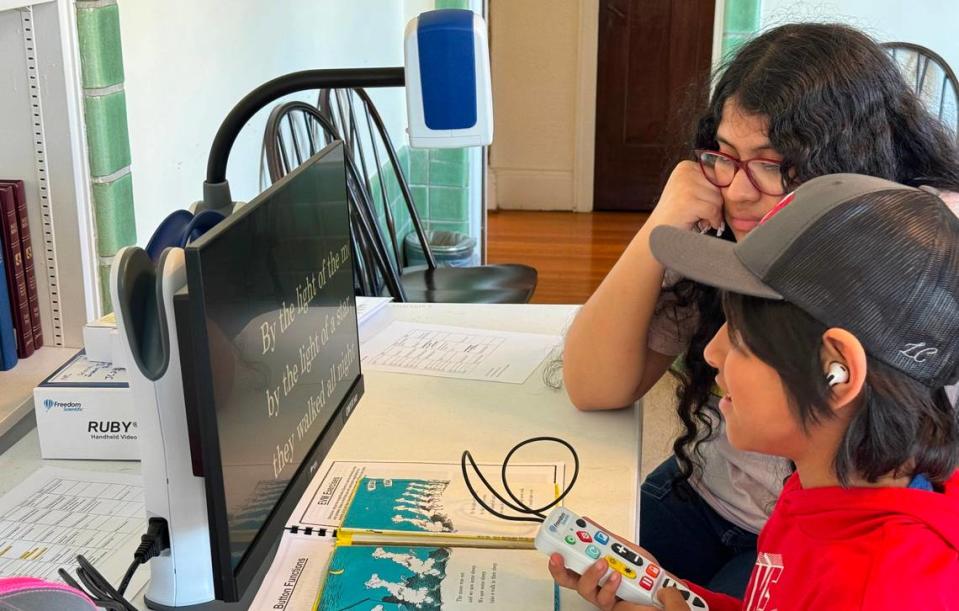

Since their vision impairment is more severe than Nyla’s, they’re getting a full suite of equipment: a larger and more powerful version of the Ruby device (the “7 HD”); two different portable video magnifiers; and two sets of monoculars.

“Do you want to see something cool?” Veronica Tafoya asks Juan.

The manager of the low vision program for Sight Savers America adjusts the camera mounted on a monitor in front of them, presses a button on a controller, and suddenly, Juan’s face fills the 22-inch screen.

“Whoooa!” the fourth-grader exclaims as he pops up out of his chair, his jaw dropping slightly and his eyes widening significantly.

Before Juan and Selena had arrived at First Presbyterian Thursday afternoon for their training on this $3,300 portable video magnifier, Tafoya had pretty much predicted this kind of response. “Sometimes the kids, when they see their faces for the first time, they get excited,” she’d explained. Because normally, when kids with visual impairments stand in front of a mirror, “they look like a blur. They really can’t see the details.”

In the next room, through an interpreter, Andrea explains in Spanish that her paternal grandmother never received a clinical diagnosis but was completely blind by 30 years old. Her eyes start to glisten as she explains that her biggest fear is that one or both of her children will eventually lose all of their sight, too.

Yet she also indicates that the help her family has been getting since Juan and Selena’s diagnoses reaffirms her decision to immigrate from Mexico when she was 19.

In Mexico, Andrea explains, they don’t try to evaluate kids for things like vision problems. There, she says, parents and teachers might blame eyesight issues on laziness, or might just throw up their hands and say, “Who knows?” So she’s grateful that, in the U.S., there are organizations eager to provide resources to help kids and families who are struggling, like Sight Savers America, like IFB Solutions, like the organizations that paid for the devices her children are being trained on in the other room.

A few minutes later, Juan comes scurrying out into the foyer, pulling a rollaboard-style case that carries his new $3,300 “toy” and being trailed by Selena, who is clutching the box with their Ruby.

“They are ready,” announces their trainer, Veronica Tafoya, “to use it all.”

Someone asks the kids what they think of it, and Juan practically sings his answer: “It’s goooooooood!”

Then they cart everything out to Andrea’s white minivan, load up, pile in, and head back to Albemarle with — at least for the foreseeable future — the promise of a clearer view of their world.