Through the eyes of Faye Johnston: The war years and the opera house

Faye Johnston, age 93, was recently reading the Cheboygan Tribune, enjoying “The History of the Opera House.”

A familiar name caught her eye, Sophie Fultz, nicknamed Grandma Shy. Fultz wrote a series of letters to her grandson in 1964. In the letters, Fultz recounted her memories of the Cheboygan Opera House when she was a child in 1900. Fultz was a neighbor of Mayor Hank Todd who ran the Opera House at the turn of the century. She spent many happy days there. Johnston knew Fultz personally. Faye, the farm girl from Broe Road and Fultz, the city socialite from the Victorian Era, not only met in Cheboygan but shared a common bond.

Faye Cadieux Johnston grew up on farm about 5 miles from Cheboygan. She had eight sisters and three brothers. The family raised pigs, beef, chickens and milk cows. They grew hay for the animals and cut it with their team of draft horses. They had a garden to feed the family. Cheboygan summers consisted mostly of chores. Faye fed the horses and cows, but she had a hard time trying to milk the cows when her father couldn’t. Her mother stayed out of the barn if at all possible. Faye picked so many cucumbers, she can’t stand them to this day. When electric lines were first installed in the area, the family could barely afford it. To keep expenses down, her father only allowed only one light to be turned on at night.

Every winter, for eight years Johnston walked to Schanick’s School. Kids bought their own lunches, usually peanut butter sandwiches. They went to school regardless of the weather. There was never a snow day, but if the snow was too bad, many children didn’t come. On those days, the class played games all day.

With the start of World War II, all three of Faye’s brothers enlisted and shipped out. This was hard on the family, especially her mother. With no phones and no means of contact, news from the war was slow. Some letters were six weeks old when they finally arrived.

Eventually the family bought a radio, “about the size of a modern refrigerator,” with big glass tubes in back. At home in the evenings, the family sat beside the radio and listened to news of the war and war songs, the Andrews Sisters, Frank Sinatra and Pat Boone. Their father listened to every Joe Louis boxing match. Faye enjoyed “Fibber McGee and Molly,” a sit com about a working-class family, “Oh, the noises they would make,” Johnston said.

One night she was sitting upstairs in her room, looking outside and watching a storm gather. Rain fell hard. She watched the lightning crack. It hit the power lines. A ball of fire raced down the lines and right into their house. The radio exploded with a sizzle and set the curtains on fire. Quick thinking on her father’s part averted a fire. The radio was thrown out into the rain and the curtains extinguished.

When it came time to go to high school in 1942, Faye wanted to go, but there was no transportation. It was too far to walk. When the family wanted to go to town, they caught the Greyhound bus. It cost a quarter. The bus dropped them off at the Ottawa Hotel, where Ottawa Park now stands. The upstairs was demolished and only a few rooms were rented. The busy bar downstairs hosted class reunions and dance parties. But a daily round trip bus ride from the farm to the Ottawa Hotel was too expensive to get Faye to high school.

It was a common practice for the farm girls who wanted to go to high school to take live-in servant positions with the wealthy ladies in Cheboygan. In return for their work, the girls had a place to stay and food while they went to school in town. Faye took her first job in town in 1942. Her first employer was Mrs. Alda Duncan who lived in a fancy house on Court Street where the Cheboygan Historical Society stands today. Mr. Bob Duncan had tuberculosis and was in the sanitorium in Gaylord. Sometimes Faye and Alda took the Greyhound to go visit him, but Mrs. Duncan was often bedridden and afraid to leave the house. Faye took care of her and the house in exchange for room, board and four dollars a week.

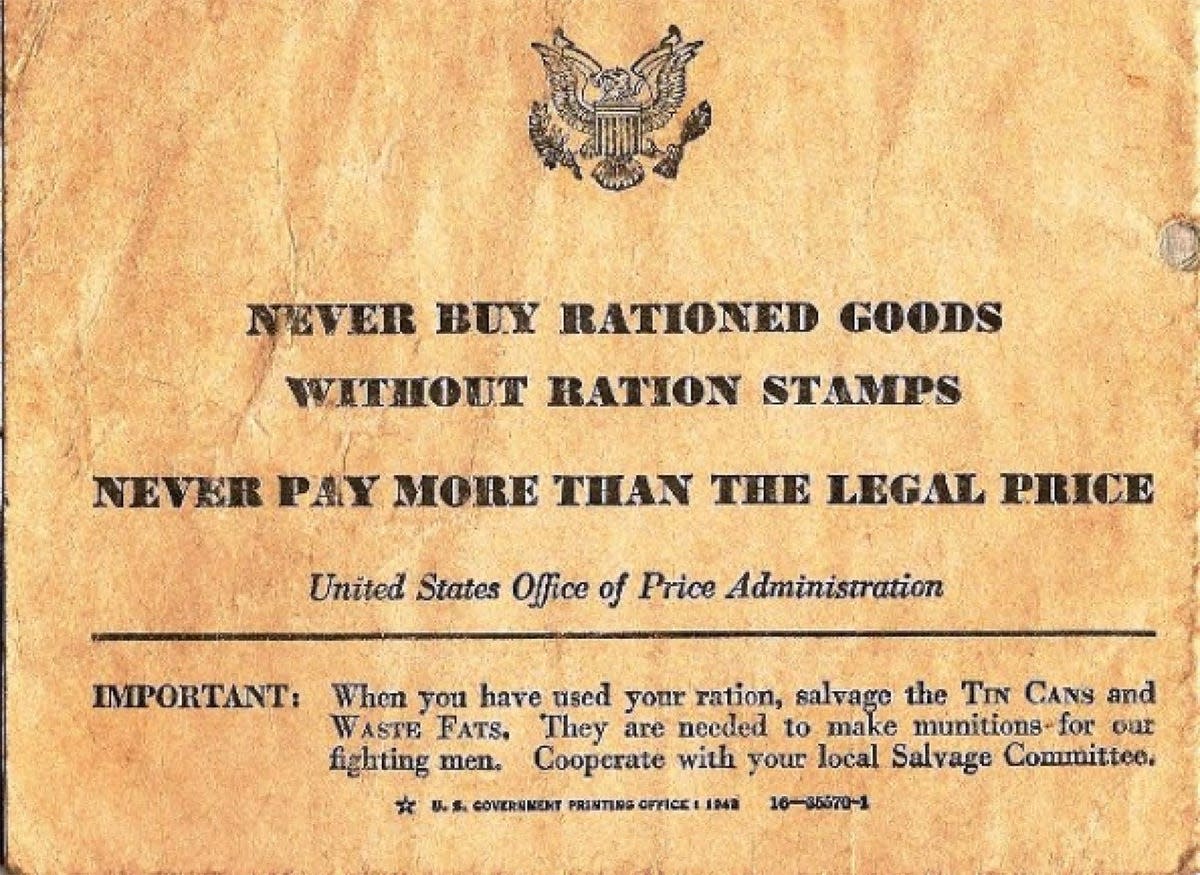

Like many of the servant girls, she had to bring her own war Ration Stamps to help buy food. During World War II, every American was issued ration books, with removable stamps. People could not buy rationed items critical to the war effort without stamps. These items included gas, fuel oil, tires, shoes and key foods like meat, butter and coffee. In order to buy these products, costumers had to give the grocer the correct stamp along with payment.

On Aug. 14, 1945, Johnston witnessed the end of an era and its impact on Cheboygan. On V-J Day, or Victory over Japan Day, President Harry S. Truman announced that Japan surrendered unconditionally. The war was over. Crowds thronged to Main Street. People cheered, cars honked, church bells chimed and above it all, the great bell of the Opera House rang out in victory. “It was the greatest celebration Cheboygan ever had,” Johnston said. Her brothers all returned home safely.

To be continued...

— Kathy King Johnson is former executive director of the Cheboygan Opera House.

This article originally appeared on Cheboygan Daily Tribune: Through the eyes of Faye Johnston: The war years and the opera house