‘This f---ing virus’: Inside Donald Trump’s 2020 undoing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Brad Parscale was on the phone with President Donald Trump and top White House officials in mid-February when someone on the line asked the campaign manager what worried him the most.

Parscale, speaking from his Arlington, Va. apartment, had just told the president how good his internal poll numbers looked. But now he had an urgent message: The coronavirus was a big problem – and it could cost him reelection.

Trump was perplexed. The economy was strong. The president had built an enormous political infrastructure and was raking in hundreds of millions of dollars. That month, Trump’s campaign conducted a $1.1 million polling project showing him leading prospective Democratic challengers even in blue states such as Colorado, New Mexico, and New Hampshire.

“Sir, regardless, this is coming. It’s the only thing that could take down your presidency,” Parscale told the president.

Trump snapped.

“This fucking virus,” Trump asked dismissively, according to a person with direct knowledge of the exchange, “what does it have to do with me getting reelected?”

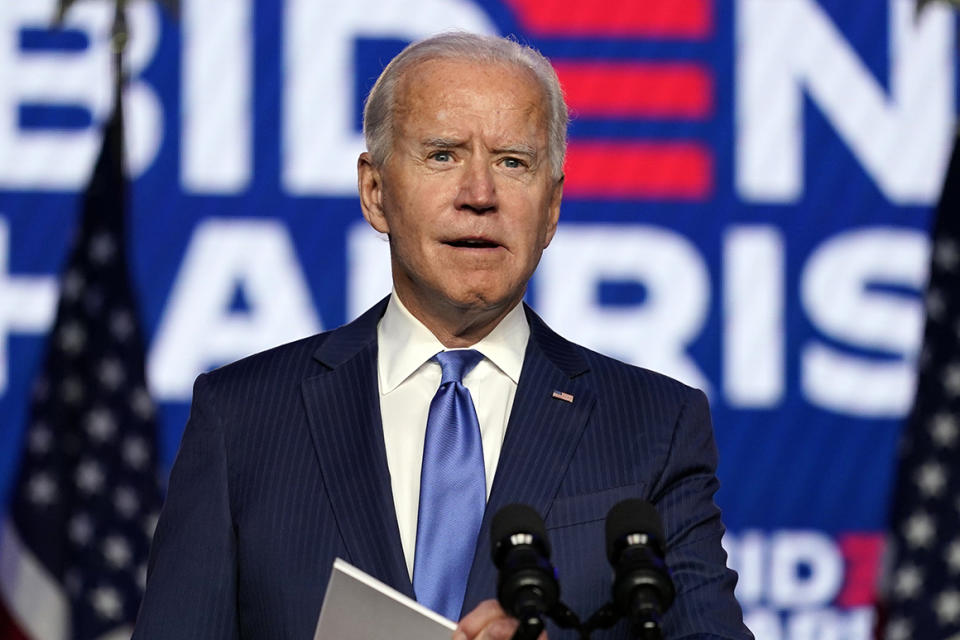

That was exactly the attitude Joe Biden expected from the president. And Biden saw his task as unambiguous.

Create a contrast. Follow the scientists whom Trump ignored. Wear a mask, halt public events and reinvent campaigning to avoid putting people in harm’s way.

When Trump resumed mega-rallies in the midst of the pandemic – a move the Biden team viewed as reckless and unthinkable – the campaign was stunned by the questions it faced.

“Reporters were asking us why we weren’t doing that?” Biden senior adviser Anita Dunn said of Trump’s rallies. “‘Why aren’t you traveling more? Aren’t you a bad campaign?”

Biden was ridiculed for holing up in his basement. He was second-guessed by pundits and even his own allies. It was evidence of a Democratic Party consumed by paranoia that the reality TV star — seemingly impervious to scandal and immune to the normal laws of politics — would manage to outmaneuver them once again.

This account of the 2020 presidential campaign is based on conversations with more than 75 people in and around both campaigns. It is the story of two candidates with completely divergent views on how the nation would respond to a deadly virus outbreak — and acted accordingly, setting up a stark choice for voters.

Among the findings:

• Communication between the Trump campaign and Republican National Committee broke down for much of the final stretch, and the two sides clashed over strategy. The RNC thought Trump’s ads were of such low quality that it created its own commercials.

• A pro-Trump super PAC took months longer than expected to materialize, prompting anxiety at the highest levels of the president’s cash-poor campaign. At one point, former top Trump strategist Steve Bannon was in discussions about helping to steer the group, an idea major donors would have rejected. By the time casino mogul Sheldon Adelson stepped forward to fund it, the president had been swamped by pro-Biden ads.

• Trump offered to cut his campaign a check heading into the final week of the race. His advisers told him it wasn’t necessary — the campaign had enough resources. While people close to the president defended the decision, it ensured he would be overwhelmed by Biden on the air as voters headed to the polls.

• Senior campaign and GOP officials vented that Trump’s finance team, led by former Fox TV host and Donald Trump Jr. girlfriend Kimberly Guilfoyle, underperformed and was an HR nightmare. Trump couldn’t compete with Biden’s small-dollar fundraising machine, and some donors were horrified by what they described as Guilfoyle’s lack of professionalism: She frequently joked about her sex life and, at one fundraiser, offered a lap dance to the donor who gave the most money.

• Biden aides clashed over a decision to refrain from door-knocking as part of a field operation, something campaign manager Jen O’Malley Dillon supported, to the disappointment of some staffers who feared they forfeited a major organizing tool to Republicans.

• The Biden campaign spent months pushing back on criticism of its “basement strategy,” including from its own party. It would feel vindicated when Biden remained virus-free as infections spread through the White House.

• Democratic Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, whose late-February endorsement of Biden proved to be a transformational moment for his campaign, revealed that he informed Biden advisers months earlier of his decision. But Clyburn resisted pressure from the campaign to go public because he thought it would pack more punch just before the South Carolina primary.

Trump’s campaign was dictated by the whims of the candidate — in other words, by instinct and impulse. Like the president’s four years in the White House, there was constant disarray and no consistent strategy. Biden’s campaign, by contrast, was orderly, disciplined, and leak-proof. But its extreme caution invited mockery — to the point that his basement became a symbol of his candidacy — as well as criticism for keeping the candidate shielded from public scrutiny.

Ultimately, America would reject the tumult of the Trump presidency after more than 235,000 people died in a pandemic he proved unable or unwilling to contain. Instead, the country chose the model student, Biden, who spent months without leaving his home and whose campaign skipped door-knocking, swore off campaign rallies, and didn’t even hold an in-person convention.

Biden would end up garnering more than 74 million votes, more than any presidential candidate in U.S. history. He reclaimed every “Blue Wall” state that Trump had won four years earlier and is on track to flip Georgia and Arizona. And he won on the strength of mail-in ballots, perhaps a sign that many voters didn’t mind so much that he was in his basement because they, too, were stuck in their homes.

'Massive disconnect': Trump's Covid denial

Trump was determined to play down the virus and demonstrate that it wouldn’t hold him back. So in the spring he ordered his team to draw up a plan to resume his rally schedule.

Parscale zeroed in on Florida and pitched the president on a few ideas: a drive-in rally in Tampa and an outdoor rally at a pier in Pensacola. Parscale also asked Vice President Mike Pence, who was leading the White House coronavirus task force, which state was least affected by coronavirus. Oklahoma, Pence replied.

Trump latched on to the idea of an indoor rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, preferring the energy of an arena to an outdoor venue.

Trump’s sparsely-attended June 20 rally — less than half the seats were filled — marked a turning point in the campaign. The crowd-obsessed president was furious. Parscale, who had hyped a massive turnout for the rally beforehand, was suddenly on thin ice.

The relationship between Trump and his longtime aide chilled. No longer did the president call Parscale “my Brad.” When Parscale left the room after a meeting ended, the president would roll his eyes dismissively.

As June turned to July, the normally self-assured president was privately acknowledging he was losing. Trump’s internal polling showed him dropping 11 percentage points in Colorado since February. Other private GOP surveys had Trump trailing Biden in traditionally conservative states like Arizona and Georgia.

Kushner began to take on an even more hands-on role. The Trump son-in-law was demanding details on everything from finances to messaging, and requesting meetings with House and Senate leaders to talk over campaign plans.

Others were warning the president he needed to change his tune.

Tony Fabrizio, the Trump pollster, penned a 79-page memo, distributed to White House and campaign officials July 21, urging Trump to reverse course on an array of issues. Trump should be encouraging supporters to vote by mail rather than bashing it; he should first focus on addressing the coronavirus before opening the economy; he ought to issue an executive order mandating the use of face masks rather than mocking them. So at the same time the nation’s top infectious disease expert, Anthony Fauci, was calling for mask use, the Trump campaign’s top pollster found it was good politics.

“The president’s overall numbers are down significantly across the board, hitting the lowest point in many months on a number of core measures,” Fabrizio wrote, adding that Biden led by 9 percentage points nationally.

“There is still a massive disconnect between what the public thinks POTUS is focused on — the economy, Fabrizio wrote, “and what they want him to focus on — fighting coronavirus.”

Parscale and Republican National Committee Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel pleaded with Trump to stop his daily coronavirus briefings; at one of them the president infamously suggested injecting people with disinfectant to eradicate the disease. Advisers tried to focus the president by sitting him down for messaging briefings with pollsters Fabrizio and John McLaughlin.

Kushner, meanwhile, had been quietly talking to the president about possible personnel changes. On the evening of July 14th, he convened an off-the-books meeting with deputy campaign manager Bill Stepien and the president in the White House Dining Room. Twenty-four hours later, word began leaking out to reporters that Stepien was replacing Parscale as campaign manager.

The shakeup underscored the degree of instability in the reelection effort with just a few months until the election.

'Don't be pushing him out': Biden's basement strategy

Biden policy director Stef Feldman remembers monitoring the news with Biden’s top advisers, Dunn and Kate Bedingfield, when it became clear that the coronavirus was spreading at a dangerous rate.

By March 11, a week after his Super Tuesday romp that put him on track to clinch the nomination, Biden was off the road. His team thought it would only be temporary. The campaign assembled a battery of medical professionals whom Biden peppered with questions as they all plotted their course.

As the country shut down to grapple with overflowing hospitals, Biden set up a studio in the basement of his home. The criticism began to roll in. Why was New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo dominating the Democratic response to coronavirus, and not Biden?

Some Democrats feared Trump would pull ahead at this moment, using his bully pulpit to drown out Biden. Instead, the president drowned out government scientists and the media at his briefings, and Biden and his campaign stuck to their plan of keeping a low profile.

And as the weeks wore on, Biden held his lead in the polls.

“It was clear to us that those early daily televised briefings weren’t calming people — they were making people more uneasy,” Bedingfield said.

Biden’s team marveled at something else: how Trump failed to come up with a comprehensive strategy to attack the virus. This was a moment that needed a gesture like George W. Bush’s megaphone on the rubble in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks, advisers mused with Biden, and Trump was whiffing it.

“I often think about the fact that Trump had at his disposal such tremendous resources, the power of the United States federal government and all of the scientists who work at those agencies is immense,” Feldman said, adding the Biden camp wasn’t privy to all of it. “We now know Trump was outright lying to the American public about the threat.”

In the early summer Biden’s campaign was besieged with “Biden in the basement” taunts from Trump.

And Democrats were still doubting him: On May 4, former top Obama advisers David Axelrod and David Plouffe, two architects of Obama’s White House victories, wrote a stinging op-ed in the New York Times.

“Mr. Biden is mired in his basement, speaking to us remotely, like an astronaut beaming back to earth from the International Space Station,” they wrote. “While President’s Trump’s well-watched White House briefings have been, for him, a decidedly mixed bag, video of the president in action has been a striking contrast to the image of his solitary challenger, consigned to his basement.”

That set off a stir. It especially stung considering O’Malley Dillon had come from Obama-world — and now some of the party’s grand poobahs were dunking on her organization.

“There was tumult inside the campaign,” a donor close to the campaign said. “That got things churned up [and] caused everyone to reassess.”

Though Biden’s staff agreed on the so-called basement strategy to keep him safe, they still had to fend off calls from Democrats for him to get out more. And they had some top party figures in their corner.

“I told Steve Ricchetti, his chief of staff, don’t be pushing him out like they’re pushing Trump — don’t do it,” former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid said. Reid, who sometimes talks to Biden multiple times a day, said he told Biden the same.

“‘We’re getting all this pressure to do exactly what we say we shouldn’t do,’” Greg Schultz, the former campaign manager, told one confidante. “It’s important to walk the walk and talk the talk.’”

The Axelrod and Plouffe op-ed fueled long-held frustrations among the Biden team. They felt dismissed and belittled by pundits and media elites whom the campaign believed favored Elizabeth Warren or Pete Buttigieg. Adding insult, the Times created an online feature, entitled “Advice for the Biden campaign,” soliciting wisdom for the presumptive nominee. Staffers fumed as they read pointers from low-level aides in campaigns they had just defeated in the primary.

Though Axelrod later called O’Malley Dillon “a hell of a manager,” his Times piece provoked doubts about O’Malley Dillon. Some Biden aides were frustrated by what they felt was a slow pace of adding staff and ramping up the digital operation as they moved into the general election. The delay was in part due to indecision over how to move forward during the pandemic.

There was a side benefit to the conservative approach in spending, though. However unwittingly, the Biden campaign was on its way to reversing Trump’s staggering fundraising advantage.

A suddenly cash-strapped incumbent

Stepien headed to the campaign’s Arlington, Va. headquarters on July 16 with a monumental hurdle ahead of him.

The new campaign manager was taking the reins of a campaign rife with problems. As Stepien saw it, there was no set budget, poor communication between departments, and an unwieldy management structure. The campaign’s Arlington, Va. offices were mostly empty by 5 p.m. and few staffers came in on the weekends. It felt sleepy.

There were other issues: Some in the campaign felt that even junior staffers had bloated salaries. And Hannah Castillo stepped down from her position as coalitions director, a key post.

Even worse, as he pored over finances, Stepien calculated that the campaign was on track to go broke by the beginning of October; the campaign’s fundraising projections for the final stretch were far too high. Stepien put a freeze on staff raises. He also made the painful decision to cut the TV budget, one of the few discretionary funding sources he could scale back.

That August, Trump essentially ceded the TV airwaves to Biden. (Parscale has privately denied he left the campaign cash-poor and that he didn't have a budget.)

Trump privately complained to allies that Biden was outspending him on television. McDaniel told him it was a problem he was dark in her home state of Michigan. The president didn’t like the recurring stories about how he wasn’t on TV because his campaign was running out of money.

Meanwhile, Stepien was telling people privately that he saw his job as safely landing a plane that was going through turbulence. The campaign manager felt he had inherited a flawed campaign and that he didn’t have the time to fix it. As he cut costs, he and others in Trump’s orbit were now counting on a familiar savior: the mega-donor Adelson.

In early July, Adelson contacted Republican strategist and former George W. Bush adviser Karl Rove. Adelson was Trump’s most generous giver, but he was uncomfortable with the existing pro-Trump super PACs. He wanted help in creating a new outfit he could feel confident in.

By that point, the pro-Trump America First Action super PAC had been raising money for two years. But there were widespread doubts about the group in the donor community. Big givers saw it as a dumping ground for ex-White House officials like former press secretary-turned-“Dancing with the Stars” contestant Sean Spicer.

That month, Steve Hantler, an adviser to Republican mega-donor Bernie Marcus, contacted veteran Republican strategist Chris LaCivita. Would he be interested in putting a super PAC together?

LaCivita, the architect of the 2004 Swift Boat Veterans for Truth takedown of John Kerry, signed on. Organizers had also spoken with former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, who had been eager for an alternative super PAC to emerge, though the talks quickly stalled and major donors would have strongly objected to his appointment.

Word of the nascent super PAC encouraged Trump advisers, who were longing for air cover. But as the summer wore on, the Trump campaign grew antsy. Where was this much-anticipated organization? It didn’t help that Trump had antagonized Adelson during an early August phone call in which he falsely accused the mega-donor of not doing enough to help him, possibly delaying matters further.

The outfit, Preserve America, would finally get off the ground in early September with millions of dollars in funding from Adelson and Marcus. By then, the Trump campaign had gone a full month getting clobbered by Biden on the airwaves.

The Trump team’s summer blackout may have been costly: Exit polls showed that more than 70 percent of voters decided on whom to vote for before September.

Infighting, lap dance jokes and hot tub parties

As they struggled to address the cash woes, Trump’s advisers had another headache: Guilfoyle, the campaign’s fundraising chair.

Republican Party and campaign officials were convinced that Guilfoyle’s team, which was beset by infighting and departures, was vastly underperforming. There was anger over their abrupt cancelation of a late September virtual fundraiser with the president that was supposed to rake in as much as $15 million just ahead of the third quarter deadline.

Senior campaign officials, meanwhile, had been getting reports that Guilfoyle had been berating her staff. Appearing together at fundraisers, Guilfoyle and her boyfriend, Donald Trump Jr., would banter in sexually suggestive ways that made some donors uncomfortable.

During a December donor event at Trump Hotel in Washington, Guilfoyle offered to give a lap dance to whoever raised the most money, according to two people who were present and another person who was familiar with the episode.

And at an event in Jackson Hole, Wyo. earlier this year, Guilfoyle and the younger Trump joked about how she raised money while in hot tubs. Another attendee presented a slightly different version, saying that whoever in the audience raised the most money would be offered a hot tub party with Guilfoyle.

And at a fall 2018 fundraiser headlined by country star Toby Keith, Guilfoyle cracked that her boyfriend liked it when she dressed up as a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader, according to an attendee.

Guilfoyle’s team has pushed back on assertions they weren’t taking their jobs seriously enough or raising enough money, pointing to a series of high-dollar events it had pulled off. As for her comments at fundraisers, Trump campaign spokesman Tim Murtaugh said, “There was nothing offensive about her presentations in context.”

Guilfoyle’s operation became another chaotic distraction for the reelection effort. Many campaign aides saw it as such a disaster that they tried to distance themselves and cut off contact with her team.

Clyburn changes the game

Biden’s money struggles were of another sort.

Last fall, his online spending had plummeted, dropping Biden to near the bottom of the primary pack. He was regularly blown away in the money chase by Pete Buttigieg, Elizabeth Warren and especially Bernie Sanders.

When Biden placed fifth in the New Hampshire primary, International Association of Firefighters president Harold Schaitberger, one of Biden’s earliest backers, picked up his phone to this taunt from a friend: “‘Hey, what’s that flushing sound we hear? Is that you and the campaign going down the commode?’”

With billionaire Mike Bloomberg having entered the race as a well-funded moderate alternative, donors were threatening to bail before Biden reached his supposed South Carolina firewall.

But just before the first in the South primary, the state’s most powerful pol, Democratic House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, stepped up to endorse Biden.

In a recent interview, Clyburn revealed that he had known for a year that he would endorse Biden but held out on making it public. One week before the South Carolina primary, back in Washington, Reps. Bennie Thompson, Marcia Fudge and Cedric Richmond, a Biden campaign co-chair, called Clyburn into a meeting. They urged him to pull the trigger on his endorsement.

“They were getting nervous,” Clyburn said. “I told them I was going to endorse but I had to do it on my schedule because I didn’t want to just endorse, I wanted to win the race.”

He couldn’t have scripted it better. Biden swept South Carolina, triggering a sequence of events that would transform the Democratic primary and erase Biden’s fundraising woes. Both Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar promptly dropped out. The next night, several of Biden's top primary election rivals joined him at a raucous, pre-Super Tuesday rally in Dallas.

As Klobuchar spoke to the crowd to formally endorse Biden, the Minnesota senator said she felt the emotion of the moment wash over her. She looked up and spotted Jill Biden, who was seated watching the event. Klobuchar could see she felt the same.

“I noticed that Jill was crying,” Klobuchar said. “She was crying really hard.”

Soon after that rally, millions of dollars poured in as Biden romped across the country on Super Tuesday. But a general election against Trump would be another matter. Trump was boasting a billion-dollar juggernaut that threatened to steamroll Biden.

The pandemic upended that dynamic, however. Biden’s team, now led by O’Malley Dillon, who had headed Beto O’Rourke’s short-lived presidential bid, pivoted by capitalizing on the ease of holding virtual fundraisers over Zoom. It was free of the hassles, time and cost involved in arranging for a candidate to travel.

Biden’s campaign contributions multiplied exponentially.

At a rally in Des Moines, Iowa, on Friday, Biden met briefly with former governor and Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. The two laughed about Biden’s newfound fundraising prowess, as Biden recalled ending his first campaign for Senate, in 1972, with $20,000 in debt.

“I don’t think people have totally gotten their arms around the fact that in two months,” Vilsack said, “he’s raised three-quarters of a billion dollars.”

After Kamala, 'Money went gaga'

The other key decision that would drive Biden’s campaign finance turnaround was his choice of a running mate.

Kamala Harris had long been seen as the most obvious pick. But Biden was wary. Two people who had direct conversations with Biden as recently as February said the former vice president brought up Harris’ aggression at the first debate in which she seemed to imply he was racist. The attack was all the more surprising because of Harris’ friendship with Biden’s late son Beau, who as a fellow state attorney general had developed a close friendship with Harris.

“He was disappointed in her because of her relationship with Beau,” said one of the people who spoke directly to Biden. “They had more than just a political relationship.”

Ultimately, Biden put aside the debate dust-up, listening to his sister Valerie, and, above all, Jill.

“Beau thought really, really highly of her,” a Biden adviser said. “They were genuine friends. And above anything, Joe values Beau’s judgment.”

Harris’ selection injected enthusiasm into the campaign — one of the knocks on Biden — by crystallizing the general election match-up in a way that Biden clinching the nomination hadn’t quite done.

“The seminal moment in the campaign was picking Kamala. The big money is the chemistry between the two of them, the combination between the two of them. Look at the day after he picked her, money went gaga, went crazy,” said Dick Harpootlian, a longtime Biden friend and donor. Harpootlian recalled hosting one of the campaign’s first fundraisers at his home last year. “We raised $115,000 and everybody was tickled pink,” he said. “Go forward over a year. He’s doing $365 million in a month.”

In August, Biden shattered records by raising that amount, surpassing Trump’s total by $154 million. A month later, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died, setting off another tsunami of Democratic cash from liberals alarmed by the looming rightward shift of the court. Biden raised $383 million in September — including an astonishing $100 million in the weekend after her death — beating Trump by $135 million in the month.

By summer, Biden campaign officials started looking ahead. His lead was holding, and if he won, he’d be inheriting a government with gaping personnel holes. Flush with cash, Biden’s advisers made a secret decision to start raising money for his transition to power.

“There was a parallel discussion discreetly happening behind the scenes about the transition. Because the Trump administration was so understaffed, there were so many vacancies, they knew they needed to crisis manage on day one,” said a person directly involved in the transition effort. “The campaign made a strategic decision to start hiring people and getting people vetted. There were people raising [money] in $5,000 increments to help pay for it.” The fund has raised more than $5 million.

'A low moment for any Republican president'

It had been three months since coronavirus struck when the video of George Floyd’s killing shocked the country.

Mass protests and demonstrations erupted, as well as destructive riots. Liberal activists began a rallying cry to defund the police.

Within days, Biden delivered a major address to discuss systemic racism, proposing reforms to curb excessive use of force by police. But most significantly to the campaign, he went on record against defunding law enforcement.

The “defund” movement was technically less about starving police departments of money than about how to demilitarize law enforcement and expand social services.

But in this the eyes of Biden’s team, those specifics didn’t matter at the moment. What did matter was that Biden not parse words. Trump’s aim was to damage Biden among independents and "never Trump" Republicans, while dividing the left and moderate flanks of the Democratic coalition.

But Biden’s unequivocal statement — “No, I don’t support defunding the police," he told CBS News in early June — defanged Trump.

The president viewed the unrest through an entirely different lens. As nightly newscasts showed images of riots, he praised the police and threatened to send in federal troops. His remarks set off a new round of criticism that the president was stoking racial division.

Trump managed to outdo himself with his St. John’s Church moment. Law enforcement used chemical spray to disperse protesters demonstrating peacefully in Lafayette Park, so Trump could have a photo op holding up a Bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church.

“The St. John’s moment was a low moment for any Republican president,” said Bryan Lanza, a former Trump adviser. It was intended as “a George W. Bush moment at the Twin Towers,” Lanza added, but “it just didn’t unfold that way.”

'Why did Trump yell ... for 90 minutes?'

Neither summer convention gave Trump or Biden a bump in the polls. So the next critical opportunity to shake up the race was the first debate on Sept. 29.

The pressure was on Biden, who had uneven debate performances during the primary. He went off the campaign trail to prepare. Trump made a bizarre claim ahead of time that if Biden ended up doing well, it would be because his campaign injected him with drugs.

It was Trump who delivered a debate performance unlike anything Americans had seen. Aggressive and volatile, he repeatedly interrupted Biden and talked over moderator Chris Wallace.

“The most fucked moment of the last 30 days was how everyone felt during the first debate. Why did Trump yell at Joe Biden for 90 minutes straight? No one knows. That was one of the worst debate performances you could have in a general election,” a senior Trump adviser said.

“Let’s say Trump loses and you want me to say what was the biggest factor in the past two months — I would say it was the first debate over him getting coronavirus times 1000.”

At that debate, Trump also appeared to invite armed supporters to show up at polls on Election Day while refusing to denounce the Proud Boys, a far-right neo-fascist group that had already grown violent in street protests. That set off a flurry of worried calls among Biden donors and supporters the next day.

In one call with high-dollar donors, the question came up: Wasn’t Trump scaring off potential Democratic voters? More troubling: Trump had also refused to promise to accept the results of the election — what if he refused to leave the White House?

Why wasn’t the Biden campaign raising hell?

As the campaign gave behind-the-scenes assurances, one notion held steady and the attitude came from Biden himself: Trump was not God. The nation’s laws would win the day.

“In Donald Trump's case, you have to separate fantasy from reality,” says Bob Bauer, former Obama White House counsel who is helping head up Biden’s voter protection program. “You don't want to help him elevate his more fantastic pronouncements by overreacting to them because that's what he wants you to do.

“He wants everybody to chase him into fantasy land, and that helps him to control the narrative.”

Trump gets it

Trump kept holding big rallies, even in states seeing a resurgence of the pandemic.

Then, it happened.

In the early hours of Oct. 2, a game of telephone and text tag broke out across senior Biden campaign leadership, with aides waking one another in the middle of the night to relay the news. Trump, the ultimate denier of the dangers of Covid-19, had the virus himself.

Some top aides with potential exposure were told to get tested before dawn. Later that morning, a small group of advisers called the vice president.

“His first reaction was concern — the president of the United States being sick is no inconsequential thing,” said Bedingfield, who was among those on the call. Biden, she said, wanted to put out a statement publicly wishing Trump well. Biden then revealed some frustration. What about all the people at the debate? Had they been exposed?

“I do think someone else asked me around that time, was there any glee or gloating like, ‘Oh, we got it right and he got it wrong?’” Feldman said. “That was absolutely not the case.”

The former vice president was hardly surprised when he learned about Trump. But he didn’t gloat about it, said a longtime confidante who has advised the candidate throughout the campaign.

“It was actually sympathy for the devil,” the person said.

Trump’s diagnosis, and the many others around him who subsequently tested positive, undermined the president’s repeated reassurances that dangers of getting the virus were exaggerated. Trump was just bringing back mega-rallies, something he saw as the linchpin to his reelection. But now he could be too sick to campaign.

“The irony is, reporters spent March and April and May saying, ‘Biden is in the basement’ … ‘Biden needs to do this, Biden needs to do that,’” Dunn said. “I think Joe Biden had a very good sense of what he needed to do, which was show the American people how a president acts.”

For the president’s team, the Covid diagnosis proved to be a PR nightmare. Campaign officials grimaced at what they saw as White House chief of staff Mark Meadows’ bobbled management of the crisis. The president’s internal polling showed the crisis prolonged Trump’s slump following his rocky performance in the first presidential debate.

“When he got it, that was a really crummy night for all of us. Super worried about how sick was he going to get,” a senior campaign official said. “That was scary.”

Trouble in Trump-land

As Trump continued to trail through the summer and into the fall, tensions between the reelection effort and the RNC grew.

It was an open secret in GOP circles that Stepien and McDaniel had a strained relationship. No one could pinpoint why. But ever since the early days of the Trump administration, when Stepien was serving as White House political director and McDaniel was starting her tenure as RNC chief, the two just didn’t seem particularly close.

Now, with just a few months until the election, it was clear that the two were operating in separate silos. There were few conversations about money, and the campaign had scaled back its use of Deep Root Analytics, a consulting firm the committee had brought on early to help micro-target advertisements. Stepien, like some other GOP operatives, was known to be a skeptic of the RNC’s data machine and was increasingly leaning on two data strategists, Bill Skelly and Matt Oczkowski, to provide analyses.

Campaign officials also doubted the accuracy of the RNC’s voter modeling and said that just before the election they received over a half-dozen estimates from the committee for expected turnout, leaving them with little sense as to what was accurate. (RNC officials say it’s typical for them to provide multiple turnout scenarios to campaigns, but that they never got any questions from the campaign about the data they’d supplied.)

Four years earlier, the Trump campaign and RNC had worked in tandem to use the same set of voter data as they pushed people to the polls. In 2020, they were effectively in different orbits.

RNC officials, meanwhile, were critical of the TV commercials the reelection effort was airing and which the president had approved. The bombastic voiceovers turned people off, committee officials thought, and there wasn’t a targeted effort underway to reach the right voters. The RNC, with the blessing of the president, began taking steps to air its own TV commercials.

The problems wouldn’t get ironed out until a few weeks before the election, when the two sides met at the RNC’s Capitol Hill offices to discuss to ensure they were working off the same sets of data to target advertisements. They put forward a united front a few days later, when Stepien and McDaniel held a press conference call in which they announced the launch of a joint $25 million TV ad blitz. While things were more functional between the two sides, officials from the two groups privately acknowledged they were putting up a facade of unity.

The final week

As he entered the final weeks of the contest, Trump grew increasingly confident, seemingly impervious to the criticism all around him. The president had surrounded himself with a crew of loyalists who’d been with him on his victorious 2016 campaign. Air Force One’s passenger list included Hope Hicks, Stephen Miller, and Dan Scavino, people who’d never left the president’s side. Trump advisers like Kushner didn’t believe the widespread public polling showing the president headed for defeat. Traditionally red states like Ohio and Iowa were safe, they were convinced.

While Democrats were making inroads in Georgia and Arizona, the Trump team felt confident they would hold on. And the president was even improving in Michigan, which the president’s team was long pessimistic about.

The idea that Democrats were trying to make a play in conservative Texas, Trump’s campaign felt, was absurd. All the campaign needed was the final week to go well.

Some battleground polls tightened late in the race, prompting nervousness among Biden staffers who had clashed internally about the decision not to knock on doors as part of its organizing efforts. O’Malley Dillon had been among those who instead sought to “meet voters where they are” — digitally or by phone. Long discussions ensued among top-level aides divided over the matter.

Those who supported door-to-door organizing didn’t understand the decision, given that the staff was well trained by then in Covid-19 protocols and would have known how to keep a distance while talking to voters. They grew increasingly skittish as they watched Republican voter registrations soar at the same time that they had forfeited a powerful turnout tool.

The campaign later relented in some states, but it was too late in the campaign to make a big difference.

Biden was investing heavily on TV ads at the time. But Trump was staking his presidency on rallies and an aggressive national door-knocking effort. Aides wanted to replicate the final days of the 2016 race, when Trump held numerous rallies each day.

Still, the president couldn’t quite let go of something.

Trump had weeks before told reporters that he was open to dipping into his bank account, but he’d never followed through on it. But with Biden dominating the airwaves, the president posed a question to some of his closest advisers: Should he open his wallet?

No, they told him, there wouldn’t be enough return on his investment. The campaign already had a substantial amount of money invested in advertising and get-out-the-vote efforts, they said.

In those same days, Steve Ricchetti, one of Biden’s top campaign lieutenants, had phoned Clyburn in what the congressman described as a “nervous” call.

“Anything we need to do? Are we missing anything?” Clyburn said Ricchetti asked last week. “He was feeling pretty good about things.”

So much circled back to the messaging that Biden and his advisers had settled on at the beginning: “Restore the soul of the Nation.” The message seemed to get more potent with each major phase of the campaign: believing science during a pandemic and not politicizing safety measures, like masks; not stoking divisions during racial unrest; insisting that the rule of law will dictate the vote count and the presidency.

“The historical moments in my view, as selfish as it may sound, was how the campaign and his core supporters stood our ground,” Schaitberger said of those who stuck with Biden through Iowa and New Hampshire.

“Stay the course. Don’t back up, don’t back down. Don’t blink. Keep pushing forward. Just stick it out. And here we are.”

CLARIFICATION: This story has been updated to more accurately reflect a conversation between former Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale and Vice President Mike Pence.