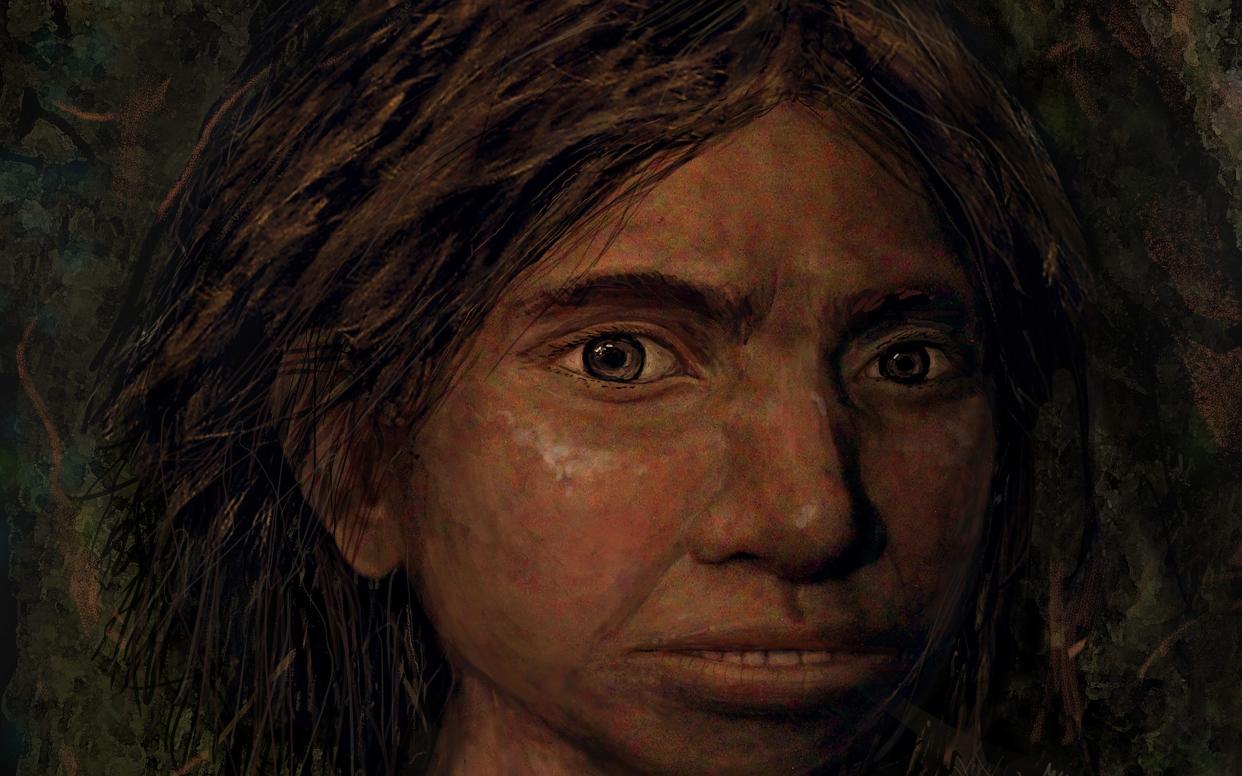

Face of one of our most mysterious ancestors revealed from DNA

The face of one of our most mysterious ancestors has been revealed for the first time after scientists used a groundbreaking technique to tease out facial features using just DNA.

Denisovans lived at the same time as early modern humans and Neanderthals, interbreeding with both before they became extinct, meaning we still carry some of their genetic code.

But archaeologists have only found a handful of teeth, one finger bone, a piece of jaw and a section of arm bone from six individuals in Russia and China, which has made reconstructing their anatomy impossible.

Now, instead of relying on bone structure, genetics experts instead looked at DNA code and specifically how different genes were expressed, which influence appearance.

“We provide the first reconstruction of the skeletal anatomy of Denisovans,” said Dr Liran Carmel, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“In many ways, Denisovans resembled Neanderthals, but in some traits, they resembled us, and in others they were unique.”

Experts are not sure when Denisovans died out. All the remains date from between 40,000 and 60,000 years ago but genetic analysis suggests their DNA was still being passed to humans as late as 15,000 years ago.

The researchers found 56 anatomical features in which Denisovans differed from modern humans and Neanderthals, 34 of them in the skull.

For example, the Denisovan's skull was probably wider than that of modern humans or Neanderthals. They likely also had a longer dental arch, so bigger mouths.

The researchers first compared DNA patterns between the three hominin groups to find regions in the genome that were differentially expressed.

Next, they looked for evidence about what those differences might mean for anatomical features based on what's known about human disorders in which those same genes lose their function.

“By doing so, we can get a prediction as to what skeletal parts are affected by differential regulation of each gene and in what direction that skeletal part would change - for example, a longer or shorter femur,” Dr Gokhman said.

They then tested the method on two species whose anatomy is known: the Neanderthal and the chimpanzee and found that roughly 85 per cent of the trait reconstructions were accurate. They then used the technique to reconstruct the anatomical profile Denisovan.

“Studying Denisovan anatomy can teach us about human adaptation, evolutionary constraints, development, gene-environment interactions, and disease dynamics,” added Dr Carmel.

“At a more general level, this work is a step towards being able to infer an individual's anatomy based on their DNA.”

The research was published in the journal Cell.