Facebook Just Made a Time Syncing Breakthrough

Facebook has launched a free timing synchronization service with server endpoints around the world.

Global timing has ramifications for science, the economy, communications, and more.

The existing standard is ntpd, and Facebook tested it against competing protocol chrony.

Facebook has taken a break from the election business to make a breakthrough in global synchronized timekeeping. The tech titan has compared the two leading time protocols used in networks and done a battery of tests to find the best one, and now the public can tap into its free time resolution service. You can try the service at time.facebook.com.

To understand the innovation a little better, think back to Office Space, where the desk jockeys decide to steal unnoticed fractions of a penny:

Our heroes mention this scheme is also integral to the evil plot in Superman III, where the fractional embezzlements of Richard Pryor’s unemployment savant brings him into his villainous boss’s schemes. This is called salami slicing, and it happens not just in financial situations, but in academic research and more.

The same kind of phenomenon of computing can throw off clocks, because computing doesn’t have an inherent sense of timekeeping and can shed parts of seconds over and over. And if enough time passes, these fractions add up to critically mismatched hardware or software trying to launch spaceships or pair up scientific equipment.

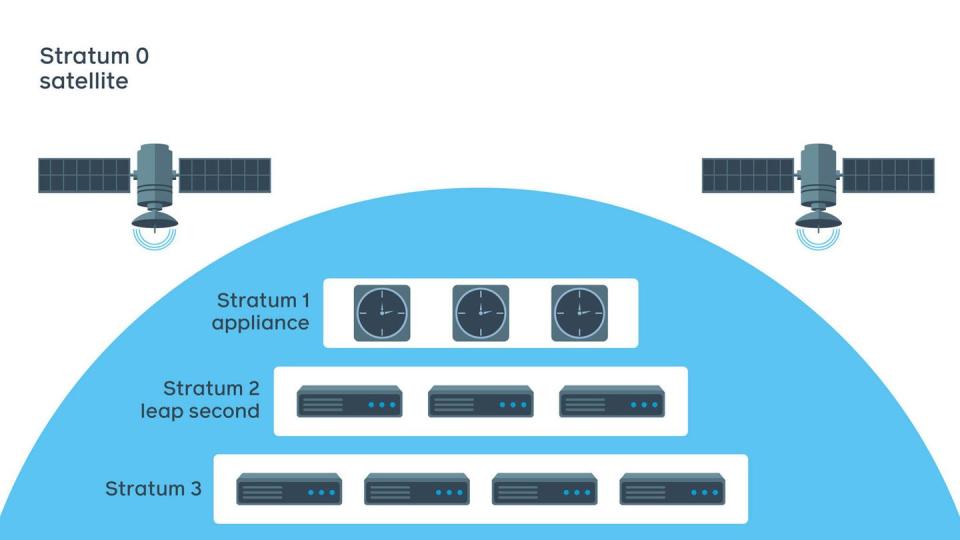

It’s here that Facebook has entered the timing fray. With careful engineering and problem solving, the company has increased clock accuracy from within 10 milliseconds to within 100 microseconds. That’s a factor of 100. Facebook has used the current standard for “analog” timing, an atomic clock device, then branched out with network hardware to try to ensure that all the connected items could be synchronized.

Now it gets even fussier to think about, because hardware itself adds tiny amounts of extra time as signals travel through it. And different networked devices have sensors that are capable down to different levels of “resolution” of time, too. Imagine putting a classic album on a turntable with a fine receiver and speaker setup, but then listening to it through a smartphone call.

Facebook is improving the wheel, not reinventing it. What Zuck and co. are working on is a new version of an old technology idea called network time protocol (NTP), which is part of the same set of ideas that includes SSH, HTTP, FTP, and DNS servers. In other words, that’s just about everything that works together to make the application end of the internet into a secure and smooth experience for users.

So Facebook began with the widely used existing technology and compared it head to head with a newer and less traditional one. The status quo NTP setup is called ntpd. The newcomer, relatively speaking, is called chrony. Both are lowercase, because . . . programmers.

In networks, newer isn’t always better—these are the communications that underpin the entire internet and the government-only predecessors that led to it. In a way, they’re the descendants of telegraph and telephone networks. Sometimes, the classic ways these decades-old network technologies are implemented are still the best ways because of how established, fine tuned, and stable they are.

During their battery of comparisons, the Facebook team found one version was the clear winner: “Both ntpd and chrony provide estimates that are somewhat true. In comparing ntpd with chrony, our measurements indicate that chrony is far more precise, which is why we’ve migrated our infra to chrony and launched a public NTP service.”

What does that mean? Well, the new Facebook NTP service offers five endpoints that cover the world, which ensures anyone who wants to align their network clocks with the new NTP service will have coverage wherever they are. When you type a domain in your browser and it’s resolved by a DNS, that, too is coming from some server in a real physical location that can vary depending on server load and other factors.

Having many far-apart locations to ping means one or two can go out while the other three or four can keep distributing time synchronization. Facebook also swears the servers aren’t collecting IP addresses or other data, but they should make sure they show their work on that before making any big decisions.

You Might Also Like