Facing death threats and no pay, mayors are the front-line commanders of the coronavirus pandemic

Mayor Nan Whaley has faced her share of emergencies in Dayton, Ohio.

A rapid-fire line of tornadoes tore through her city a year ago. In August, a mass shooting left nine victims dead and 17 wounded. Whaley now spearheads her city's response to the coronavirus pandemic, aware that the challenges of this crisis will last longer than anything she's dealt with before.

“You quickly realize it’s a marathon and not a sprint to the other side,” she said. “You have to kind of hold your energy in for the long haul.”

Unlike last year, when she faced the tornadoes and the shootings on her own, mayors across the country are dealing with the same problems.

“We’re figuring it out together,” she said. “I’ve never felt closer to my fellow mayors than I feel right now.”

'Dear Mr. President, please stay home!': Baltimore mayor asks Trump not to visit city amid lockdown

Front-line commanders

Mayors didn’t come up with the "locally executed, state managed and federally supported” approach that President Donald Trump has adopted for combating the coronavirus. But they’re the front-line commanders.

While governors have been in the spotlight, mayors have been seeing up close, every day, how much longer a neighborhood bar and grill can go without customers before it must permanently shutter, how many masks the senior center has left, how long the food bank lines are and how many of their own employees might soon be out of a job.

Some have faced death threats and racist attacks for their stay-at-home orders, making life and death decisions that might go against actions taken by their governors or state supreme courts.

At least one is forgoing her salary as she, like most mayors around the country, struggle with unprecedented budget holes.

Others repurpose city workers, turning librarians into government aid researchers and parking enforcers into park rangers.

As mayors stay in constant contact with each other, swapping ideas and sharing best practices, they figure out ways to help businesses reopen and reward those that do it safely. They’re thinking ahead to what they want their communities to look like when the pandemic is over, hoping to use the forced disruption as a chance to innovate and solve long-standing problems.

Mayors face some of the same struggles as their constituents – a spouse sick with COVID-19 or children learning from home – as they tackle what some say is one of their most important jobs: helping their community cope mentally with the incredible uncertainty and projecting confidence they’ll get through it.

Vaccine: China gets 'promising' early results from COVID-19 vaccine trial

"You're a counselor. You're a helper. You're a healer. ... You're a visionary," said Bryan Barnett, mayor of Rochester Hills, Michigan, and president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors. “There's so much emotion and uncertainty in our communities right now. And the one tremendous advantage that mayors have is that they have the public's trust more so than any level of government.”

A recent poll backs him up.

Most trusted and hardest hit

Seventy-two percent of voters surveyed this month by the Harris Poll say they trust statements from their mayors about the spread of coronavirus. That’s slightly higher than the 68% who trust statements from their governor and far higher than the 44% who trust what Trump says.

Voters rate local governments’ response to the coronavirus better than that of governors and the president, despite the fact that cities have been hit hard.

Cities are home to a disproportionate share of those most vulnerable to the pandemic – low-income people and people of color, said Amy Liu, director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution. That’s made them more cautious about lifting social distancing restrictions, even as both Democratic and Republican governors have moved toward reopening, she said.

“Not only do we see, nationally, tensions between the governors and the White House, but even across the country, there are some tensions between cities and their states about managing reopening,” Liu said. “And that is why we're seeing such a patchwork recovery right now.”

Florida test questions: FDA investigates tens of thousands of COVID-19 test results

Death threats and racist attacks

One of the worst days of Mayor G.T. Bynum’s life was in March when he ordered the closure of all bars and restaurants in Tulsa, Oklahoma – two days after the governor encouraged Oklahomans to follow his lead and dine out.

When Bynum later issued a shelter-in-place order, many people thanked him, but others compared him to Hitler, he wrote in an opinion piece for The New York Times.

In Nevada, Reno Mayor Hillary Schieve surprised most of her staff when she became the state’s first elected official to call for the closure of businesses March 16.

Immediately after nonessential businesses were shuttered, the phones at City Hall blew up. The police department increased security for City Council members and Schieve.

“We were getting these calls from people in major panic, major fear. I was getting text messages,” Schieve told the Reno Gazette-Journal.

Schieve, a kidney transplant recipient, is immunocompromised, so she spends most of her time self-isolating at home.

What scared Schieve was when a man began making threatening calls the next day to the secondhand clothing store she owns. The store is staffed mostly by teenagers, who called her in a panic.

“They were calling me, saying a guy was calling and saying he wanted to rape me and kill me,” Schieve said. “The guy kept calling and threatening.”

A short while later, Schieve said, she was on a conference call with fellow mayors from across the country to give advice to those considering their own closure orders.

“What I was telling them was, ‘Listen, for those of you who have not been in this situation yet and are contemplating making the move, you need to understand the magnitude of what happens and the stress and panic of what comes along with it. So be prepared,’ ” she said.

Absentee voting: Republicans, Democrats push ahead as Trump blasts Michigan over it

The daughter of Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms happened to be looking over her shoulder the day in April when her mom received a text using a racial epithet and telling her to “shut up and reopen Atlanta.” The text was also sent to one of her other children.

Bottoms shared the text message on Twitter to make people aware that, even in a pandemic, “there’s still people who are attempting to divide us.”

"I found it important that people see what this still looks like," she said. “This is not something that people of color make up in their head. This is something that still happens every day in America.”

How to reopen

The reopening debate has been particularly hot in Georgia where Bottoms has been outspoken in her criticism of Gov. Brian Kemp’s controversial plan to lift restrictions even as infections were rising. She said she hopes that, despite her opposition, Kemp made the right decision because there’s no benefit to her constituents to her being able to say, “I told you so.”

“There’s not a mayor in the country – a sane mayor, anyway – who wants to be at odds with their governor,” she said. “It’s not a good place to be because there’s so many things that we have to work together on and rely upon each other on.”

In Columbia, South Carolina, where Mayor Steve Benjamin has taken more restrictive steps than the governor, he likened it to “trying to create your own culture here in your own city.”

“We’re in a position where we’re not determining when we reopen,” he said.

"So if we can't determine when, we need to figure out how.”

Churches: Trump calls for Memorial Day church reopenings but sends mixed signals on enforcement

For Benjamin, that includes coming up with a public seal of approval for businesses following best practices. It means spearheading a national “Mayors for Masks” initiative to distribute more than 1 million masks to city residents – and standing in a parking lot to personally distribute those in Columbia. And it means frequent communication while trying to model safe behavior.

“I stay on the news even though I haven’t had a haircut in two months,” Benjamin said. “I look horrible.”

Wear a mask in public? Sure. Majority of Democrats, Republicans say they have, survey shows

Massive budget gaps

Metropolitan areas drive the nation’s economy, and the massive budget gaps cities face as tax revenue and other income fall off the cliff will prolong the recession without extensive federal assistance, said Mark Muro, policy director at Brookings’ Metropolitan Policy Program.

“It will lead to massive layoffs and program and service cuts at a time when those are greatly needed,” he said. "It's hard to put together the scale of the fiscal problem."

Local government employment was down 801,000 in April, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Overall job losses are of a magnitude not seen since the Great Depression, the economic disaster that sparked the creation of the National Conference of Mayors.

The situation was so dire then that mayors said, “we’ve got to go meet the president,” said Tom Cochran, CEO and executive director of the conference.

“This organization was very much born into the Depression, and (we) also were a big part of the recovery,” he said.

Similarly, mayors today appeal to Washington for help.

In New York, Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan encourages residents to contact Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. She stopped taking her salary of nearly $135,000.

A message to our residents and city employees: pic.twitter.com/7JYHaZJyHI

— Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan (@MayorSheehan) May 16, 2020

Expecting an $18 million revenue shortfall, Sheehan said she faces devastating cuts in personnel and services without federal assistance.

Sheehan held off announcing layoffs to see whether the Senate would react to the House passage of a relief bill that included $150 billion for state and local governments. A final decision will have to be made soon.

“Every week that I delay, the more we have to cut,” she said. “The only way to get those level of cuts is to stop providing certain services.”

Vision for the future

Despite the challenges, Madison, Wisconsin, Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway laughed when asked if she’s second-guessing her decision to run for the post last year. She didn’t get much “normal” time in office before the pandemic hit. She’s made difficult decisions such as keeping her city’s restrictions in place after the state Supreme Court struck down the governor’s stay-at-home order.

She’s already thinking ahead to how she hopes Madison can come out stronger.

“The pandemic has really highlighted the gaps in our society. It’s brought even more attention to the racial disparities and economic disparities,” Rhodes-Conway said. “I think we have an opportunity, as we start to grow our economy again, to grow something that is more equitable, that is more sustainable.”

Projecting a positive vision for the future is important, said Barnett, the Rochester Hills, Michigan, mayor who leads the U.S. Conference of Mayors, shortly after finishing a Zoom call with about 50 business owners.

“My goal on that call was ... to exude confidence and support for what they’re doing,” he said. “Because I know they look to me, and if I were to be discouraged or despondent, that sets a tone that I'm not interested in setting."

He keeps up his own spirits through a call he hosts every Friday with mayors across the country.

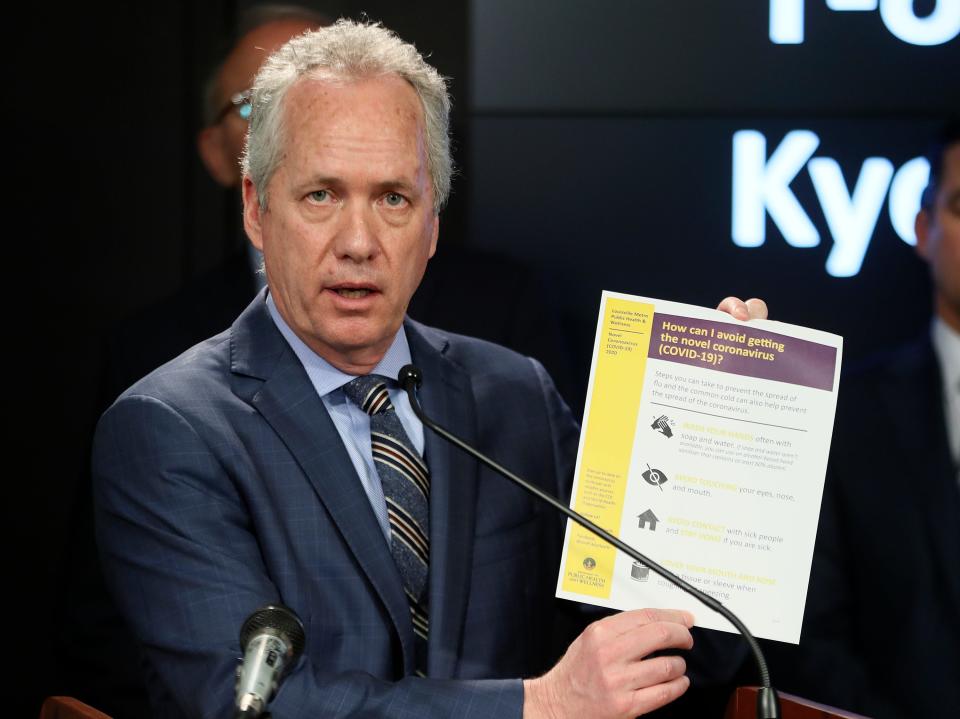

Likewise, in Louisville, Kentucky, Mayor Greg Fischer has encountered unprecedented challenges “but also a lot of unprecedented joy.” The city launched a “Lift up Lou” initiative that includes daily online activities – such as education programs, art activities and “mindfulness” sessions. There's a community song created with the help of 30 musicians led by the city’s orchestra conductor. The song helped raise money for a “One Louisville” relief fund to help households, businesses and organizations affected by the pandemic.

“We’ve become closer in one way by being further apart,” he said. "And when we're on the other side of this thing, we'll all have more tools in our toolbox to create a better city."

'Impacting all of us'

Fischer has worked long days on such initiatives even as his wife, a physician, became infected with COVID-19, something he didn’t publicly share until she improved.

“It was very difficult,” he said. “Gratefully, she’s in good shape.”

In Atlanta, Bottoms was chairing a virtual economic development meeting Thursday morning when she realized she’d forgotten to wake up her son for a virtual learning class.

“I had to run up two flights of stairs,” she said. “So I’m handling (the pandemic) the same way people across America do it each and every day."

That’s a difference from other crises mayors have dealt with when constituents might not have felt their leaders knew what they were going through, Bottoms said.

“But this, for sure,” she said, “is something that’s impacting all of us.”

Contributing: Anjeanette Damon, Reno Gazette-Journal.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus: Mayors are front-line commanders of the pandemic