After facing persecution as a Rohingya in Malaysia, she's now devoted to helping refugees in Milwaukee

Growing up as a refugee in Malaysia, Hasnah Hussin was barred from public education, so she hung around the homes her mother cleaned, learning the alphabet and numbers from Malay families.

When she finally was allowed into school under a pilot program for refugees, she struggled to keep up. When she failed a math class, her mother’s advice became the guiding principle of her life:

“There are two choices in life, always,” Hussin recalled her mother saying. “Whether you fight and continue for your dream, or give up and blame destiny.”

“I selected the first choice, and the second has never been something I’d consider.”

Today, at 31, she has devoted her life to helping refugees.

Hussin is Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic minority that has faced persecution in Myanmar, formerly Burma. Her parents were among the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who fled violence in recent decades to neighboring countries, including Malaysia. The U.S. last year declared that members of the Burmese military committed genocide against the Rohingya, only the eighth time since the Holocaust the U.S. has determined a genocide has occurred worldwide.

Milwaukee, where Hussin and her family would settle in 2021, is believed to be home to the largest population of Rohingya refugees in the country.

Like generations of immigrants, they are finding their way in a new land. Research shows their presence is necessary if the city is to grow and thrive.

Hussin is now a refugee education coordinator at Catholic Charities, helping newcomers adjust to life in the U.S.

Although Hussin was born in Malaysia, her Rohingya identity meant she was stateless, not recognized as a legal resident of her birth country or her parents’ country.

More: Meet Sesame Street’s new Muppets, on screens now thanks to Milwaukee’s Rohingya community

In Malaysia, few opportunities, many roadblocks

Living undocumented as a refugee wasn’t easy. Her mother worked four jobs to earn enough money to support her family. And as a teen, Hussin’s invitation to compete at the national level in track and field, and in rugby, was revoked when organizers learned she was a refugee.

When her father was found to be undocumented at his construction job, authorities deported him to the Thailand border, where he was sold to a fisherman. When he got sick from malnutrition, the crew threw him into the sea, Hussin said. Another boater rescued him.

As an adult, still in Malaysia, Hussin worked as an interpreter for the United Nations’ refugee agency, UNHCR, but felt limited by simply relaying information. Then, at a Malaysian nonprofit, she conducted research on Rohingya refugees, fed hungry people during the pandemic, and helped women fleeing domestic violence.

“My main motivation — I do not want another child to live my life. I do not want another woman to face what I faced,” Hussin said.

When, in 2021, she got word that UNHCR selected Hussin and her family to resettle in the U.S., she didn’t believe it at first. It was the fifth time she’d been called for the medical test that precedes the flight to America, but nothing had come of it before.

This time, it was happening. Her young daughter would get a chance at an education.

Compared to other cities, Milwaukee has affordable housing, plentiful jobs

After a stay with her sister in New Hampshire, Hussin, her daughter and her parents moved to Milwaukee for her job at Catholic Charities. She develops educational materials and trains volunteers for citizenship and English as a Second Language programs. That she speaks seven languages herself comes in handy.

To be a refugee in the U.S. is different than in Malaysia. Here, staff and volunteers at resettlement agencies set up newly arrived refugees in furnished apartments, help them secure jobs, provide initial cash assistance, take them to appointments and teach them how to ride the bus, among other tasks. In turn, they are provided with legal, permanent residency.

Refugee resettlement is continuing to rebound from the lean years of the Trump administration, when the program was gutted. President Joe Biden set an annual cap of 125,000 refugees, but the country resettled less than half that number in the last fiscal year as agencies raced to expand their capacity.

Wisconsin has seven resettlement agencies, each affiliated with a national agency. Three are based in the Milwaukee area. Wisconsin agencies resettled about 1,400 refugees in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, compared to 636 the year prior (when agencies were also resettling several hundred Afghan evacuees and Ukrainians, most of whom aren’t counted in refugee totals). This year, 81% of refugees to Wisconsin came from Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Those totals also don’t account for refugees like Hussin who were resettled in one state and later moved to Wisconsin, a phenomenon known as secondary migration. Local experts say they’ve noticed many Burmese refugees moving from other states to Milwaukee, which has become something of a hub for persecuted Burmese ethnic groups such as the Rohingya, Karen and Karenni.

More: At Milwaukee's most multicultural Catholic church, southeast Asian refugees find a 'spiritual home'

Relative to other metros, Milwaukee has affordable housing and plentiful jobs, and many find success. Homeownership rates are high among Burmese, local resettlement agency staff say.

Compared to those in Malaysia, the refugees Hussin works with in Milwaukee are more empowered, she said. They are allowed to work and go to school, and their basic needs are met. The focus is helping them navigate entirely new systems.

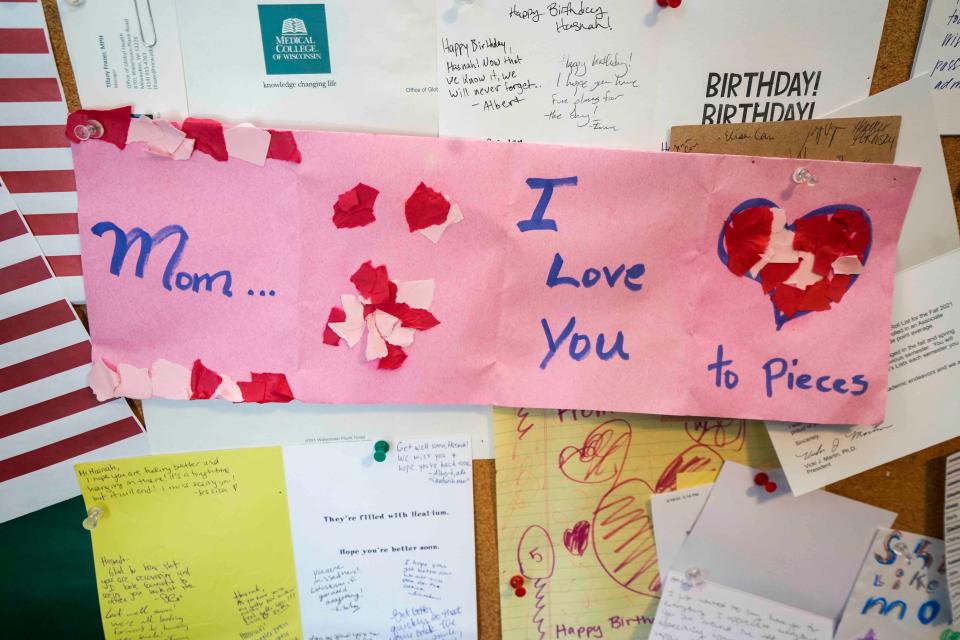

Hussin’s daughter, now 6, is a “mini American,” Hussin said, her office walls decorated with grade-school art projects. “Mom, I love you to pieces,” reads one adorned with shreds of construction paper.

Hussin herself is working toward an associate’s degree in human services from the Milwaukee Area Technical College and hopes to pursue bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Some people have told her she’s not a good Muslim woman — that she should stay home and raise her daughter; that she belongs in the kitchen, not the workplace.

But if she’d followed what other people expected of her, “I would have given up a long time ago,” she said.

This project is supported by a grant from Marquette University Law School's Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education, to make possible journalism on issues of importance to the Milwaukee area. All the work was done under the guidance of Journal Sentinel editors.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Rohingya woman helps other refugees at Catholic Charities in Milwaukee