What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in Killers of the Flower Moon

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Killers of the Flower Moon might seem like a big departure for Martin Scorsese, trading as it does the mean streets of the big city for the open plains of Oklahoma. But look more closely, and this story of a community exploited and controlled by a ruthless prairie godfather (Robert De Niro), who poses as a benevolent pillar of the community while forcing his relatives to choose between family loyalty and decent behavior, is squarely in the director’s usual wheelhouse. What’s different is less glamorization of the bad guys, more consideration of the impact of their actions on the victims, and law enforcement being shown as unequivocally good.

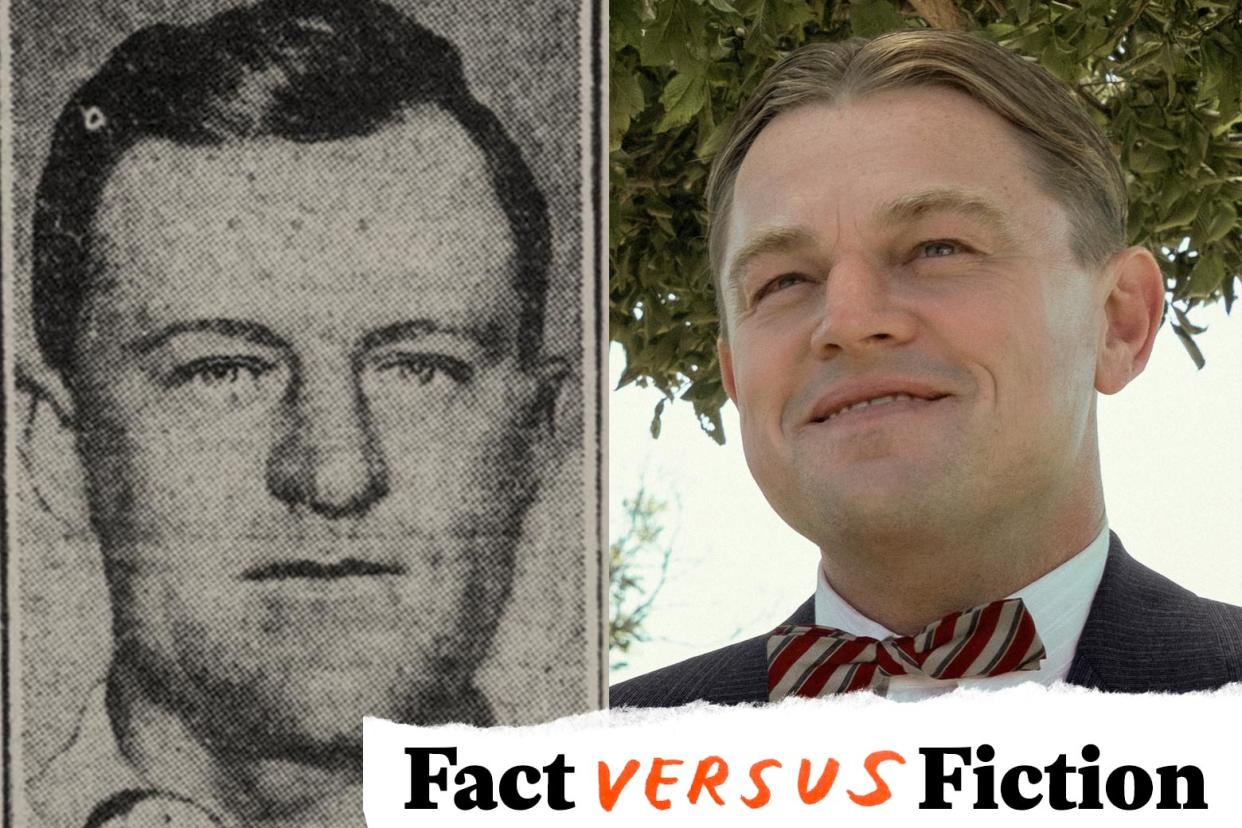

The script originally told the story of an Osage tribal family, who were murdered for their oil lease rights in the early 1920s, from the perspective of Tom White (Jesse Plemons), the agent in charge of what was the nascent FBI’s first big homicide investigation—fairly standard Scorsese. But after discussions with descendants of the victims and other tribe members, the script was rewritten to foreground the relationship between Osage oil heiress Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladstone) and her husband, Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio, channeling a French bulldog with a perpetually anxious brow and faint scowl), the latter of whom arranged for Mollie’s family members to be killed and who may or may not have poisoned her at the behest of his uncle. As well as changing the film’s focus from a police procedural to a love story, this makes the second half read as Scorsese’s nod to Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion.

The director’s previous adaptations of nonfiction books (including Gangs of New York, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas) have been notably successful. Here, we take a look at how closely Killers of the Flower Moon sticks to the true story and where it departs.

In the film, we see Mollie and other members of the Osage Nation having to ask a white merchant in their town for advances on their quarterly allowances and explain what they need the money for, as though they were children, despite being millionaires.

This is accurate. Driven by the U.S. government from their fertile lands in Missouri, the Osage were forced to live on the plains of Oklahoma, an area thought to be barren and worthless. But as it turned out, their reservation was on top of an oil field. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, the reservation’s gas and oil reserves generated more wealth than all of the American gold rushes combined in just two decades, and the Osage land became the early-20th-century equivalent of a Gulf state.

Determined to discourage the traditional model of communal ownership practiced by many tribal peoples, the U.S. government passed a law in 1887 that said reservations could be divided into 160-acre parcels of land granted to individual Native Americans for farming. The Osage negotiated a particularly favorable agreement that ensured the tribe retained communal ownership of its underground resources shared equally.

Each of the tribe’s members received a headright, or share in the oil money, that could be inherited but not sold. Headrights could be divided as they were passed down across generations, leaving multiple heirs with a portion of a single share, or one person could inherit multiple headrights (as Mollie did when her sisters died). Non-Native people could inherit headrights by, for example, marrying into an Osage family. According to David Grann, author of the book on which the film is based, in 1923 alone, the 2,000 tribe members collectively received $30 million, or $400 million in today’s money.

Uncomfortable with the thought of an extremely wealthy minority community, Congress passed a law requiring Osages to undergo a competency test (“competency” was often determined by whether a person was mixed blood or full Osage). If they failed, they were assigned a white “guardian,” usually a powerful man in the community, to monitor their spending down to the smallest personal items. Many guardians took full advantage of their position, forcing the Osage to buy goods from them at inflated prices (the guardian of Mollie’s sisters just happened to own the general store in Fairfax, the town where they lived) or directing them to friends’ businesses in exchange for kickbacks. Some guardians went in for just plain swindling. According to one government study, Osage tribespeople had at least $8 million stolen from them.

Nevertheless, in 2016 the tribe was still wealthy enough to buy Ted Turner’s 43,000- acre Bluestem Ranch in Oklahoma.*

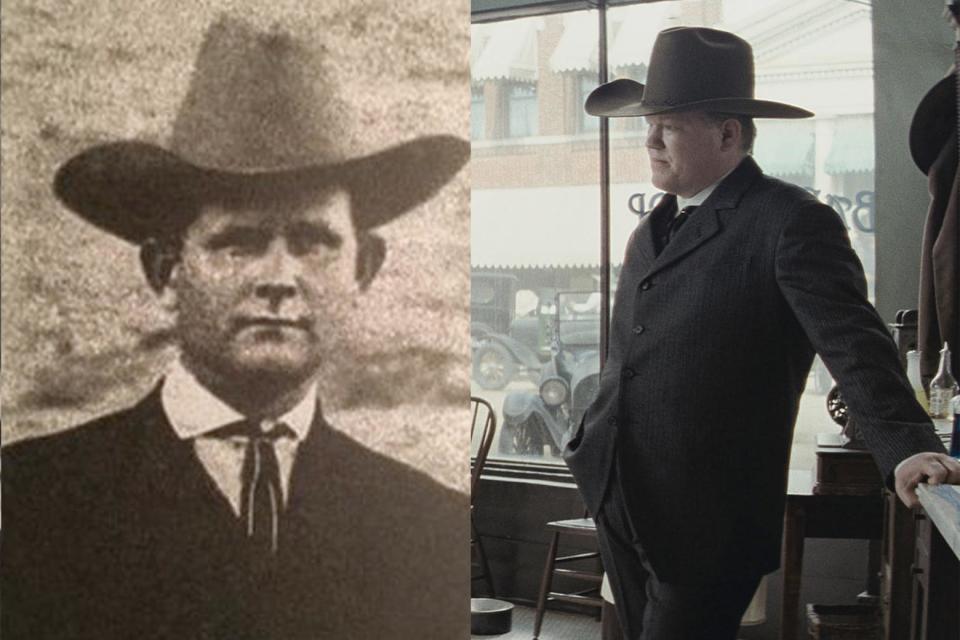

After Mollie’s sister Anna and cousin Henry are murdered, and her other sister Rita’s house is blown up, she joins other tribal elders, distressed at the number of Osage in Fairfax being killed with impunity, on a mission to Washington to appeal to President Calvin Coolidge directly. Much to their surprise, four men in black from the Bureau of Investigation (the proto-FBI) turn up and start knocking on doors, lining up informants, cutting deals, and asking uncomfortable questions, eventually bringing charges against powerful local cattle rancher William Hale (De Niro, playing Hale as a cross between John Gotti and Harry S. Truman).

The movie’s version is true up to a point. In the early 1920s, between 24 and 150 Osage died violent or suspicious deaths, most in or near Fairfax. The local authorities showed a distinct disinclination to investigate the cases properly, plus, as Grann told Smithsonian magazine, “You have morticians covering bullet wounds, doctors who were administering poison, businessmen and lawmen who were on the take, and many others who remained complicit in their silence.” A delegation of Osage did go to Washington and in 1925, the BOI’s new director, J. Edgar Hoover, did send agents—though only after the Osage offered the bureau the then-huge sum of $20,000 for its trouble.

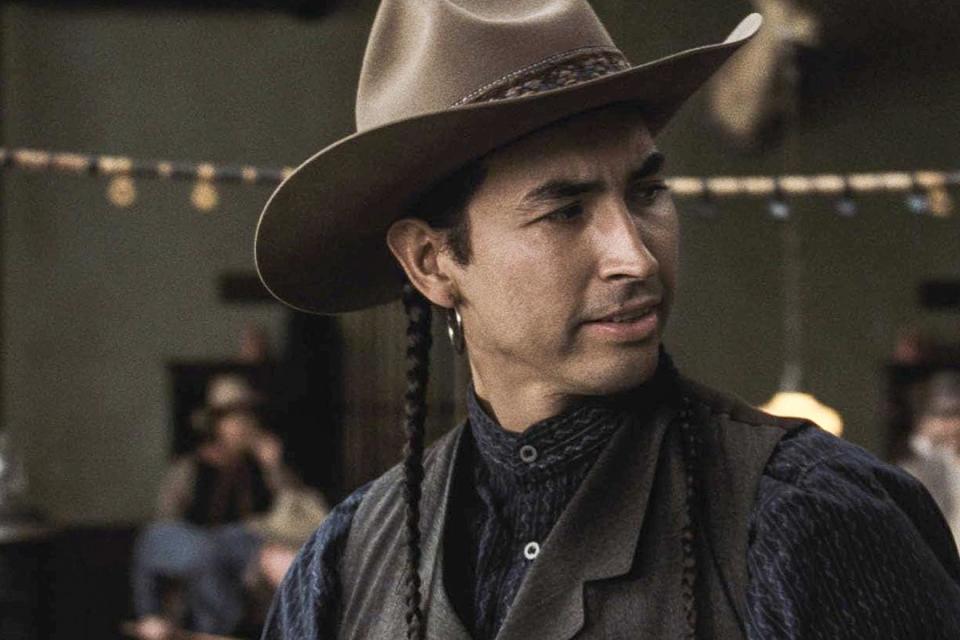

However—except for lead investigator Tom White—once in Fairfax they did not identify themselves but instead went undercover, posing as an insurance salesman, a cattle buyer, an oil prospector, and even an herbal doctor. As the film depicts, one agent was a Native American—John Wren (Tatanka Means), who was able to live among the Osage and gain their confidence.

This team arrived only after the young Hoover initially bungled the investigation. According to Grann, the BOI “released an outlaw named Blackie Thompson, hoping he would work as an undercover informant, but he instead robbed banks and killed a police officer. At one point Hoover wanted to get out of it and turn it back to the state, but after the scandal he didn’t have a choice.” Moreover, the author said, because Hoover was in a rush to close the case, once Hale was charged, the BOI “didn’t reveal a deeper, darker conspiracy, and as a result many were able to escape justice.”

Bill Hale asks his dim, wannabe-player nephew Ernest to woo Mollie and marry her, thus making their children eligible to inherit her headrights. Ernest does as he’s told but in the process finds himself actually falling in love with Mollie. She, meanwhile, is completely onto him (“Coyote wants money,” she notes) but forms a genuine connection with him nevertheless. As Ernest is drawn deeper into Hale’s schemes and becomes an accomplice in the murders of two of Mollie’s sisters, he keeps maintaining he loves her, even after he injects Mollie with a poison along with her insulin on the instruction of two doctors in Hale’s pay.

It’s hard to know what is truly in another’s heart, but Grann told the British newspaper the Independent that “all the letters and interviews I did clearly indicate he had genuine feelings for Mollie.” He also wrote in the New Yorker that “Ernest studied her native language until he could talk with her in it. She suffered from diabetes, and he cared for her when her joints ached and her stomach burned with hunger. After he heard that another man had affections for her, he muttered that he couldn’t live without her.” For Mollie’s part, even after Ernest was arrested and she was told of his role in her relatives’ deaths, Mollie reportedly said her husband was “a good man, a kind man [who] wouldn’t have done anything like that.”

In one scene, Hale ushers Ernest into the sanctum of the local Masonic temple and beats him with a paddle to punish him for talking to the BOI agents.

Hale was indeed a Mason, initiated into Grayhorse Lodge No. 124 in 1907, although he was expelled after his arrest for the murder of Mollie’s sister Anna.

When not arranging to have them killed for their oil rights, Hale likes to think of himself as a supporter the Osage, promoting their culture and befriending individual members of the tribe (which doesn’t stop him having one knocked off as part of an insurance scam), and we see him frequently speaking the Osage language.

Jim Gray, former principal chief of the Osage Nation and a descendant of Henry Roan, the friend Hale had killed to collect on a life insurance policy, confirmed to Smithsonian that Hale “spoke Osage. He ingratiated himself into the community.” Not only did Hale speak Osage, but De Niro learned the language for the role.

Frustrated by the botched investigation of her sisters’ murders, Mollie hires a highly competent private detective, William J. Burns, with offices in London, Paris, Berlin, and more. Burns, asking real questions and investigating doggedly, starts to make headway, until one night he is jumped by assailants and killed.

In fact, a whole group of Osage, including Mollie, hired private detectives from Pinkerton and the William J. Burns International Detective Agency, but the private investigators’ inquiries got nowhere. Records discovered later revealed that the agents were paid to look the other way or to stop their efforts altogether. And far from being murdered, William J. Burns became Hoover’s predecessor at the BOI, serving until 1924.

The script may be conflating Burns with an attorney, William “W.W.” Watkins Vaughan, who was engaged by another Osage Nation member, George Bigheart, who had told Vaughan he knew who the killers were and had access to incriminating documents that would prove his assertions. Shortly thereafter, Bigheart died after drinking suspected poisoned alcohol, whereupon Vaughan phoned the Osage County sheriff saying he had important new information about the Osage Indian killings and would be arriving on the first train. Thirty-six hours later, Vaughan’s naked body was discovered lying near the railroad tracks north of Oklahoma City, his neck broken.

At the end of the film, instead of the usual titles rounding up what happened to the main characters, Scorsese delivers the information by depicting a live radio show, complete with elaborate sound effects and a cameo for himself as the producer, part of a weekly series based on FBI cases.

This, it turns out, is not just a dramatic device. There actually was a radio dramatization of the case broadcast in 1932 on The Lucky Strike Hour (the version in the movie is sponsored by Lucky Strike), as well as another called “The Osage Indian Murders,” broadcast on Aug. 3, 1935, as part of a radio series entitled G-Men, created with the cooperation of the FBI.