Fair Lawn's Radburn, a planned community 'for the motor age,' was ahead of its time

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Radburn enclave of Fair Lawn was built to manage a menace.

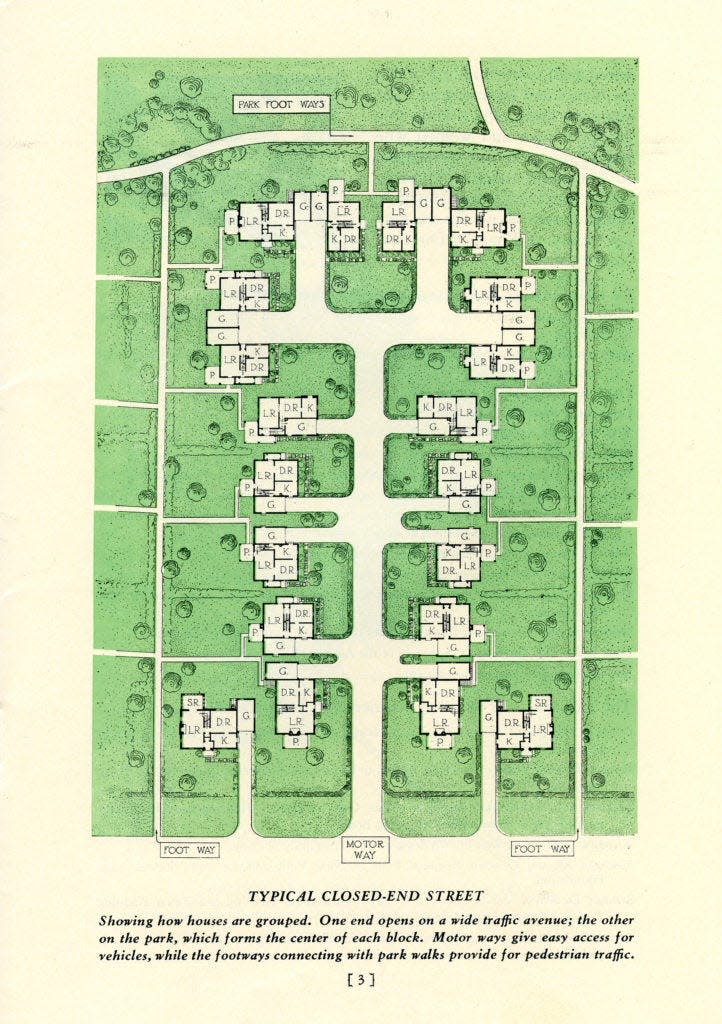

"A town for the motor age," Radburn flipped the suburban standard. The goal was to reduce the need for roads. Rather than use a traditional grid, designers placed gently curving lanes within larger "superblocks." Those lanes branch off, ending in cul-de-sacs budded with homes, encircled by walkways and braced by parkland. Parkland, not pavement, provides the community's backbone.

Though studied today as the embodiment of an ideal, Radburn is a plan unfinished. A national historic landmark, it provides glimpses of what could have been while preserving a model of early-20th-century architecture and community planning.

The planners behind Radburn were believers in the concept of the self-sustaining garden city. New York developer Alexander M. Bing, landscape architect Marjorie Sewell Cautley and architects Clarence S. Stein and Henry Wright tested some of their theories at Sunnyside Gardens in Queens in 1924. Backed by Bing's City Housing Corporation, the dense neighborhood was threaded with pedestrian pathways meant to encourage communal activity. It was proof that the concept could work for Radburn.

The ideas that shaped Radburn weren't new, Stein would admit. However, using them in combination proved novel. A variety of housing meant to be modestly priced was placed around communal parks and linked with graded pedestrian walkways. Front doors faced parkland. Garages faced cul-de-sacs that brought vehicles from exterior thoroughfares framing the superblocks. Pedestrian and vehicular traffic never mixed. A series of overpasses and underpasses did away with the need for dangerous crosswalks between homes and the shopping plaza, trail station and elementary school.

Radburn was designed to be massive. The pedestrian pathways were meant to extend to industrial and commercial parks on land leased by the corporation. When it was announced in early 1928, Bing said investors, including John D. Rockefeller Jr., had spent $3 million on more than 1,000 acres. Plans were made for 10,000 homes priced at an average of $8,000. In an editorial, The Record said the project, just 10 minutes from the developing George Washington Bridge, marked "the beginning of a new era in home development."

Ads pitched quiet living amid a community suited to raising young families. Several miles of streets, footpaths and utilities were installed, and on April 25, 1929, the first residents arrived. Radburn's designers planned three zones, each with its own shopping district and school. The community planners sorted every detail they could control. They projected a population of 25,000. But they couldn't plan for everything.

Very early on, it hit a snag with the stock market crash of 1929. Development progressed into the Great Depression, but in 1934 the City Housing Company ran out of money. Radburn's hoped-for diversity never developed, nor did its industry. The garden city would grow enough to hold only about 3,500 in north central Fair Lawn.

More: Historic Ridgewood house should be moved to a new site, consultant says

Although new townhouses now fill out the southwest part of Radburn, the Radburn Plan was never realized, and its promise went unfulfilled, said Rick Hampson, a Radburn resident, historian and former reporter for The Associated Press and USA Today.

"This was the great demonstration project of a community that, when it was built in 1929, was supposed to change the way Americans lived," he says, adding that the community once lauded and visited for its vision of the future became insular.

In the post-war era, Radburn's ethos was considered too complicated and expensive for most domestic developers to implement. The later-developed southern end of the unincorporated community is more reflective of greater Fair Lawn's development than it is of Radburn's founding vision.

More: Want some good news in your inbox for a change? Sign up for this good news newsletter

Today, homes within the community's boundaries vary greatly in size, but mostly stick to Tudor and Colonial revivals in style. There are apartments costing $200,000 and six-bedroom homes valued at more than $1 million.

All told, the Radburn ideal had minimal impact in the U.S., Hampson says. It is more accepted overseas ― in the U.K., Sweden and Japan ― as a template of development. The concept of the cul-de-sac caught on stateside, but a community designed to operate in the spaces beyond it did not.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Fair Lawn's 'motor age' Radburn community was ahead of its time