Faith: Lift up those who labor, for it is holy work

When my first wife and I shared our plans to leave Connecticut and head back to my hometown to attend seminary, a friend volunteered to help me drive our loaded moving van to Pittsburgh.

Peter was not religious, but he knew, when attending gatherings in our duplex, he’d enter the ranks of many who were. I always enjoyed the response our friend offered when asked what he did for a living: “I’m a carpenter … you know, like Jesus.”

This comparison both humbled and filled me with pride. My father worked in a warehouse as a so-called “router” for 40 years, after ending his stint in the army during World War II, during which he functioned in a similar capacity as a tech sergeant handling and distributing supplies. Though his job essentially entailed providing directions for drivers making deliveries, not until my brother and I began to work at Kauffman’s department store warehouse ourselves, did we realize his work involved use of his well-developed forearms.

In short, my old man was a manual laborer. My brother and I were as well up until we both went on to graduate school.

Loading our things into the moving van with Peter’s help, I realized I would soon surrender my laborer status for professional “white color” work. Peter would not. His remark to our house guests reminded me, as I began to prepare to become a so-called “preacher” — a minister of the gospel of Jesus Christ — that Jesus while he preached, never made the transition to the professional class. This held true for his fishermen disciples, too.

While Labor Day is a secular holiday, for those like my brother, a recently retired university professor, and me, the holiday holds a certain sacred significance. Our father’s name, like that of Jesus', was Joseph. While the two of us, like our two sisters, went on to pursue professional careers after college, the fact that we for a time, like Jesus, worked in the manner of our father means something. We both took on other manual laborer jobs after that, but our long-term goal remained: avoid making a living by our hands. Still, we recognize the importance of remembering where we started.

On occasions when I return to Pittsburgh, a working-class city at its roots, I’ve at times gotten the impression from my cousins and uncles, who’ve labored as masons, firemen and steelworkers, that they feared I might have forgotten where I’ve come from. A bit too defensively I remind them that, before I became a pastor, an adjunct professor,and a writer, I was a landscaper, a butcher, a soda jerk, a hotel maintenance man, a painter, a grocer, a toy maker as well as a warehouseman. I like to think that Jesus, too, never forgot he labored as a carpenter before he became a "fisher of folk."

I fear with the changes in global manufacturing, the rise in technology, and now the introduction of artificial intelligence, we are becoming a more, not less, caste-defined society. For a time after WWII, laborers began to enjoy a middle-class lifestyle. That middle class has diminished significantly and those who work with their hands have now been relegated to the downside of that equation. Remembering their struggle and how much we still rely on them remains as relevant as when Congress made this day a national commemoration back in 1894.

While parades, usually in urban areas, commemorated Labor Day for decades after that, most folks now more or less regard it merely as the means to another three-day weekend, marking the end of summer.

Nevertheless, while we still often hear disparaging remarks about labor unions, Americans' attitude about them overall remains positive. In fact, it has improved. According to a Gallup poll, 71% percent of the populace indicate that such unions have a positive effect on the country — the highest approval rating since 1965.

While we have come to recognize the importance of labor as an economic force, I wonder if we’ve done enough to encourage this to trickle down to a respect for the laborer as an individual.

When I served as parish associate at a church in Tacoma, Washington, a town that once boasted the largest copper smelter in the world and thus employed a large contingent of laborers, I ran into a member of our church, whom I knew made a living as an independent contractor. Frank and I ended up sitting down together and talking over our respective lattes.

During those days I tried to do much of the handiwork around our rundown rambler myself, but I shared with Frank how much I appreciated those I’d hired in tackling the bigger more complex jobs beyond my skill set. Frank then in turn talked about his own work and went on to say,

“You know, that’s what it comes down to for us: folks appreciating the work we do.”

I recently came across another statement by another Frank — “Pope Frank” (as I like to call him because of his unusual accessibility to everyday folk). You know him as Pope Francis I. The pontiff said:

“Rivers do not drink their own water; trees do not eat their own fruit;

The sun does not shine on itself … living for others is a rule of nature;

We are born to help each other … life is good when you are happy but

much better when others are happy, too.”

My contractor friend appears to have incorporated this papal understanding into his work. I wonder if we might not give laborers the benefit of the doubt and consider that this provides the modus operandi for most of them.

Might we not then treat those we employ or depend on for their labor accordingly? Might we not initiate a practice this Labor Day 2023 and simply begin thanking, as we do our military, those who labor for their service?

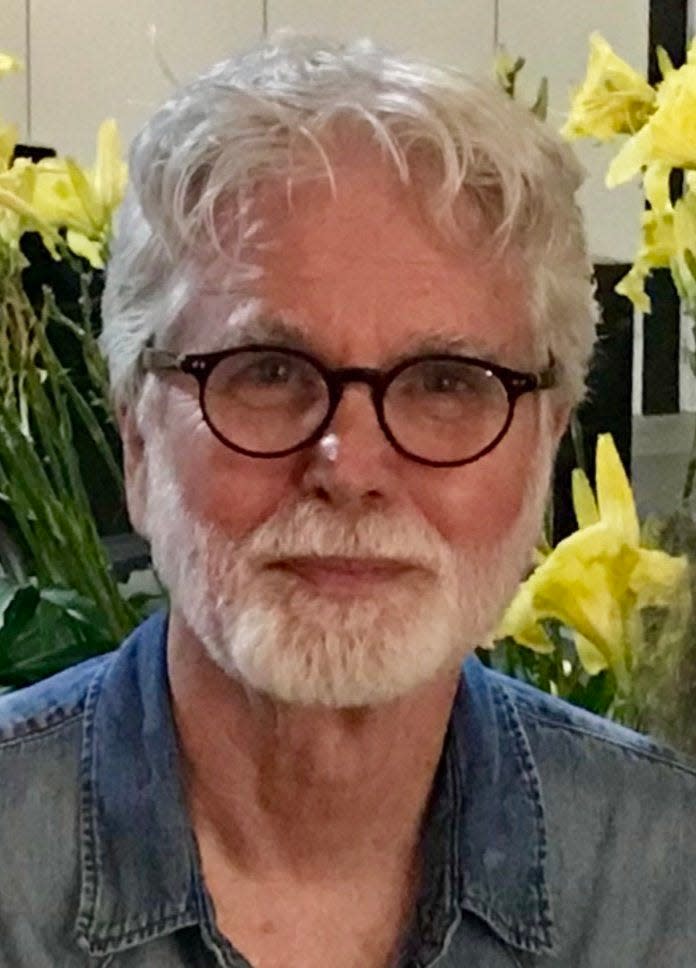

The Rev. Terry Dawson is an ordained Presbyterian minister and former adjunct faculty member of San Francisco Theological Seminary.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: A prayer for the laborer on Labor Day