The faith that stares through death

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I don’t think it’s grandiose to say that one moment of one day from the last 60 years shaped America in ways that no other day, or year, or decade has. That day was April 12, 1963. Good Friday, as it happened, which is telling because the moment in question on that day found the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. wondering why God had forsaken him.

He sat in Room 30 of the Gaston Motel in Birmingham, Alabama, puffing on a cigarette, jittery and frail from the previous night’s insomnia, looking at the two dozen aides and executives of his Southern Christian Leadership Conference who’d crowded into his room, asking them if any had a solution to the greatest problem they’d faced.

They didn’t. Which was almost to be expected, given the circumstance in which he had placed them. King and the SCLC had decided a couple weeks earlier to stage the largest civil rights campaign in the movement’s history in Birmingham, Alabama, and to either break segregation there or be broken by it. Birmingham in those days wasn’t so much a city as a site of domestic terror. Cops raped Black women in their patrol cars. The Klan castrated Black men in their homes. Local elected officials gleefully, and often publicly, referred to the city as Bombingham for all the Black homes and businesses that were dynamited. And there was never any prosecution for these crimes. It was a place whose goal was to strike fear in every Black person. CBS’s Edward R. Murrow, when he visited the city a few years prior to King’s own trip, said he had not seen anything like Birmingham since Nazi Germany.

For King, the city’s terror was the point. King’s goal there was to anger every terrible white person in Birmingham. If he did that, if he and his volunteers marched and remained peaceful even as the blows fell, he would turn his body into a vessel of suffering, into a metaphor of the Black experience. King wanted violence to be visited upon him and other volunteers in Birmingham. Because if that violence persisted, especially as, say, a New York Times reporter took notes or a CBS camera crew filmed the grotesquery, well then, these metaphors of racism and hatred on the part of white America, relayed through the means of mass communication, might find the audience King most wanted to influence. The audience of two brothers, the Kennedy brothers who governed America and would watch these metaphors, this domestic terror, from the White House. As they watched, perhaps they would at last be persuaded to side with King on the one thing he had wanted for years, and the one thing that Jack and Bobby Kennedy had consistently denied him: Real and lasting civil rights legislation, the right for Black people to be treated as fully human, which no one, not even Lincoln, had put into law.

But once in Birmingham a problem surfaced. The white brutes who ran the city were wilier than King thought. When King’s nonviolent protests attracted the national media and then the Birmingham police department’s K-9 corps — with German Shepherds attacking and almost feasting on unarmed Black volunteers and bystanders on Palm Sunday, April 7 — Birmingham public officials and judges saw they were falling into King’s trap. So they set their own. They issued a court-approved injunction. This was a ban on all future protests, starting with the one King plan to lead on April 12. This injunction did more than just forbid marches. It also set exorbitant terms for anyone who violated it: six months in jail.

And this brings us back to Room 30 in the Gaston Motel on Good Friday morning, and the greatest dilemma King ever faced. Because if he marched that afternoon and violated the injunction, the six months he spent behind bars would be more than enough time to snuff out the Birmingham campaign. To finish King and the SCLC, too. King doubted whether his organization and the civil rights movement as a whole could survive if they lost in Birmingham.

The solution was no better, though, if he fought the Birmingham injunction in court. King’s own lawyers that morning in Room 30 told him that it would take months, if not a year, to appeal the injunction to a federal court outside Alabama, where the SCLC might at last get a fair hearing.

Some aides thought he should leave Birmingham and stage emergency fundraisers in New York. But the bail for violating the injunction had doubled in the last few days from $50 per protester to $100. There were perhaps hundreds of people ready to march that afternoon, but the SCLC was effectively broke, and no emergency fundraiser could raise enough cash to cover the march’s bail fines.

Worse, if King left town, or even just refused to march, he would be pilloried in the press as he had been for years. He was seen in 1963 as a pompous pastor who could give a good speech but never lead a movement. The SCLC had not had any victories in over seven years. By 1963, other civil rights groups sneered at King and called him a “phony” for how he did all the talking and they did all the walking. It was true enough. King had not yet led a march in Birmingham. Part of the reason he promised to lead the march on Good Friday was to respond to press allegations that he always remained behind the scenes. So to refuse to march now, in Room 30, would disavow the trust of not just the newsmen but all Americans, Black and white. Who would follow the leader who could not even follow his own words?

King was left with no good choice. All options seemed like the end of the Birmingham campaign, and very likely the death of the SCLC. The mood that sunny morning turned dark. Ralph Abernathy, King’s best friend, later remembered those trials in the Easter season and in Room 30 in particular as “the work of the devil.”

King agreed. That morning, feeling hopeless, King later wrote, “I was alone in that crowded room.”

Isolated from the two dozen and, in that moment without end, from God, too.

By 1963 other Civil Rights groups sneered at King and called him a “phony” for how he did all the talking and they did all the walking.

I became fascinated with that campaign in Birmingham not just because of the courage it took King and the SCLC to go down there — King thought he and others might be killed — but because of how severely the campaign tested King’s faith. I wanted to write a book about it. King’s crisis reflected one in our own age, and in my own household.

I am a white man married to a Black woman and together we are raising our three children to understand that they embody King’s famous dream. True integration, the literal result of a couple who looked past their skin-deep differences. But the problem of America in the 21st century mirrors the problem of America in the 20th. Whatever progress we’ve made, we remain fixated on those differences. My kids first noticed this in 2020. It wasn’t just the hate that burbled in the fetid pools of alt-right social feeds or the identity obsessions that spread across the green expanse of progressive colleges, where, say, Black students were encouraged by school administrators to segregate themselves from white students in the cafeteria and white students were encouraged to not question the policy. No, my kids saw America’s real fixation with race play out in a story that reflected their family history.

Though we live in Connecticut now, my wife, Sonya, grew up in Houston’s Fifth Ward. George Floyd grew up in Houston’s adjacent and equally hard up Third Ward. In 2020, George and Sonya were the same age, 46. George had gone to Yates High. Sonya’s cousins had gone to Yates. Her cousin Derrick knew George back then. Derrick called him Perry, which was George’s middle name, and watched him as a tight end on the Yates football team that made the state championship game in 1992.

George’s murder, then, felt almost personal to Sonya, and to me, and to my mother-in-law Connie, who lives with us and who, until she retired, had spent her life in Houston. We mourned George Floyd. And because we mourned, we didn’t shield our kids from the coverage like we had the others, the innocent Black men who’d also been killed by police officers and whose deaths had also been recorded by cellphones. No, we watched George die on CNN and our kids did too, as if to tell them that this was the Black experience as well.

As our daughter Harper, then 11, and our twin boys, Marshall and Walker, then nine, watched, they became upset. Over the coming months they ran from any footage of Black people suffering, ran in tears, because they understood that nothing they did — and nothing we could do as parents — could keep them truly safe. Danger would always walk a little closer behind them than it did white children. The fear our kids felt hardened eventually into a cynicism, which wizened and calloused them to a certain extent, even protected them, but also enclosed them in a prison of their own rage. We saw it. We heard it. How everything about their country was awful and bloody and how they would move away from here just as soon as they could.

The America they were coming to understand was not a dream of any famed orator from 1963, or the multicolored reality that was their home 60 years later, but instead a bleak landscape where almost nothing changed.

And that was why I wanted to write a book about the Birmingham campaign. Not just to highlight for my children that societies do bend toward justice, if given enough time. And not just to show that the despair they felt — what my boys called a “darkness” — was what King felt, too, in Birmingham.

But the real reason to write the book was to show the truth of any darkness.

Eventually, it is followed by light.

The problem of America in the 21st century mirrors the problem of America in the 20th. Whatever progress we’ve made, we remain fixated on those differences.

With all his dark thoughts on that Good Friday morning, King rose in the suite of Room 30 and excused himself. He walked around the two dozen awaiting his decision about whether to march and opened the door to the suite’s adjoining, and empty, bedroom.

He closed the bedroom door behind him. He was truly alone now and perhaps never more distant from God. He had turned to prayer in the past when he felt unsure, unmoored, without hope. He had even written about one such incident, which had become famous in Christian circles when it appeared in his first book, “Stride Toward Freedom,” in 1958. In that episode, during the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956, a late-night phone call — “Listen, nigger, we’ve taken all we want from you; before next week you’ll be sorry you ever came to Montgomery” — had unnerved King. Maybe it was the anger in the man’s voice; maybe the forewarned date: before next week. But that night in 1956 King couldn’t sleep and it was worse than insomnia. “It seemed that all of my fears had come down on me at once. I had reached the saturation point.”

He went to the kitchen and made a pot of coffee. When it had brewed and he’d poured his cup he’d reached a conclusion. “I was ready to give up. … I tried to think of a way to move out of the picture without appearing a coward.” He couldn’t figure out how so he took his problem of saving face to God. With his head in his hands and his cup of coffee untouched before him, King prayed aloud:

“I am afraid. The people are looking to me for leadership, and if I stand before them without strength and courage, they too will falter. I am at the end of my powers. I have nothing left. I’ve come to the point where I can’t face it alone.”

He’d come to the point where he couldn’t face it at all.

At that moment he experienced the rush of God’s presence “as I had never experienced Him before.” A voice called to him or, rather, issued from within him. “Stand up for righteousness, stand up for truth,” it said with quiet assurance. “God will be at your side forever.”

The fears dissipated. His self-confidence returned. He could endure this night. He could lead this movement.

“I was ready to face anything. The outer situation remained the same but God had given me the inner calm to face it.”

The racist man’s warning turned out to be anything but idle — King’s home was bombed three nights later — but how King continued to lead in Montgomery despite his fear was why he was still leading in 1963, and often against his inclination.

What he sought now in Room 30 in Birmingham was that same inner calm. That assured voice that would tell him what to do in a situation even more threatening than the late-night phone call in Montgomery.

The noise of his inner monologue that Good Friday morning — if I proceed the campaign will die; if I delay, the campaign will, too — quieted as he at last relayed his struggle to God in prayer. Soon he found himself “in the midst of the deepest quiet I have ever felt,” King later wrote. A moment more and he was somehow standing in the center of the room, eyes open. “I think I was standing also at the center of all that my life had brought me to be.” He thought of the two dozen next door, the hundreds more ready to go to jail today if the thousands of Blacks lining the streets were any indication. All of them waiting to see what Martin Luther King Jr. would decide. His mind then leaped beyond Birmingham, and Alabama, to the 20 million Black people in America who yearned for the freedom King promised —

If only he would lead them.

Suddenly, “There was no more room for doubt.”

He took off his suit jacket and dress shirt.

From Montgomery until today he realized he had prayed to God for wisdom about how to lead but often faltered in his own execution. During the “Freedom Rides” in 1961, King had remained a bystander, unwilling to board the buses alongside other civil rights leaders who attempted to integrate the bus lines that crossed Southern states; King watched as those same buses were firebombed for their attempts. King realized now in Room 30 how his reluctance during the Freedom Rides had led younger civil rights groups, like John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to call King a “phony” and “De Lawd,” the latter a sneering bit of irony that caricatured how highly King thought of himself.

And yet was it a caricature? After all, King’s own deputy whose job was to oversee the daily protests in Birmingham, James Bevel, had become so disgusted by King’s passivity that Bevel had already left the campaign, quit it a few days ago and returned to his native Mississippi.

Now, in that empty bedroom of Room 30, King took off his dress slacks.

He realized that Bevel had left and SNCC had sneered at him and the Freedom Riders had dismissed his speeches because King’s actions as a leader had never, not really, risen to the level of his rhetoric.

He had been a phony. He had lacked the courage to truly partake in the work God had set out for him. He vowed he would no longer lack that courage.

King put on a pair of blue jeans and a denim shirt.

He stared in the mirror in the empty bedroom, in these “work clothes,” as he called them, which were suddenly as rich in symbolism as Good Friday itself. He opened the door to the other room where the two dozen waited for him.

He walked in.

King looked at the deputies of the SCLC.

“I have decided to go to jail.”

The room gasped. So Martin would march today? He would go to jail? But that meant he would stay in jail for six months! Some deputies began to raise their concerns again about the Birmingham campaign being snuffed out by King’s jail term — and perhaps the SCLC’s death, too —

King stopped their protests.

The firmness of King’s voice, what he wore even: Many of the 24 had never seen King in anything but a suit and tie. To dress like the working-class Blacks who would inevitably want to march behind him this afternoon — it showed the conviction King held.

“I don’t know what will happen,” he said. “... But I have to make a faith act.”

King’s own father, Martin Luther King Sr., stepped forward and told him he did not think marching was a wise move. Perhaps if the SCLC fought the injunction in court —

“I have to go,” Martin said. “I’m going to march if I have to march by myself.”

It didn’t come to that. The people in Room 30 were so stirred by King that not only did Ralph Abernathy and the Birmingham pastor who co-led the campaign here, Fred Shuttlesworth, ultimately agree to march alongside Martin, but soon the whole of Room 30 joined hands, King’s father, too, and together they sang the anthem that now defined the civil rights movement.

“We Shall Overcome.”

Some sang with tears in their eyes. Perhaps because the Holy Spirit moved through the room. Perhaps because so much remained uncertain. Would King be arrested? And if so, what would happen to him? Would the campaign here in Birmingham, and the SCLC, languish without its leader, languish unto death?

There were no answers when they finished singing their song.

There was only the echo of the faith they shared, the fragile faith they’d put in God.

We watched George Floyd die on CNN and our kids did too, as if to tell them that this was the Black experience as well.

I loved the fragility of that moment as I researched my book. For so many of us, faith is never steadfast and calm. It contains currents of doubt, forever pulling us under water. What surprised me as I researched was how I myself was soon gasping for breath.

My book on the Birmingham campaign — this open letter to my kids to remain courageous and faithful in life — officially began its reporting in the summer of 2020. But by November of that year I was laid off by ESPN, where I had worked for 17 years as a features writer and editor. For how long would I be able to feed my family of six?

I had no answers. I only had a faith that things would work out because I was doing work which felt like God had set out for me, a faith that, admittedly, grew more fragile with each passing day and each glance at our checking account.

As I weighed my future I returned to that morning in Room 30, searching for how exactly King persisted. How exactly did he hold on to his fragile faith as he walked out the door and into the glare of the afternoon?

He didn’t. Or rather, his faith — in himself, in God — oscillated as wildly as my own. “I was besieged with worry,” he later wrote of what was going through his head that Easter weekend. “Those were the longest, most frustrating and bewildering hours I have lived.”

So how did he persevere?

For three hours that Good Friday afternoon the press and thousands in Birmingham waited for King to march outside Zion Hill Baptist Church, the protest’s starting point. The onlookers waited so long that sweat began to drip off their foreheads and some questioned whether King would step out of the church at all.

Then, suddenly, there he was, in his work clothes, with Abernathy and Shuttlesworth behind him, bounding down Zion Hill’s front steps and hitting the street out front.

“There he goes!” a man in the crowd yelled. “Just like Jesus!”

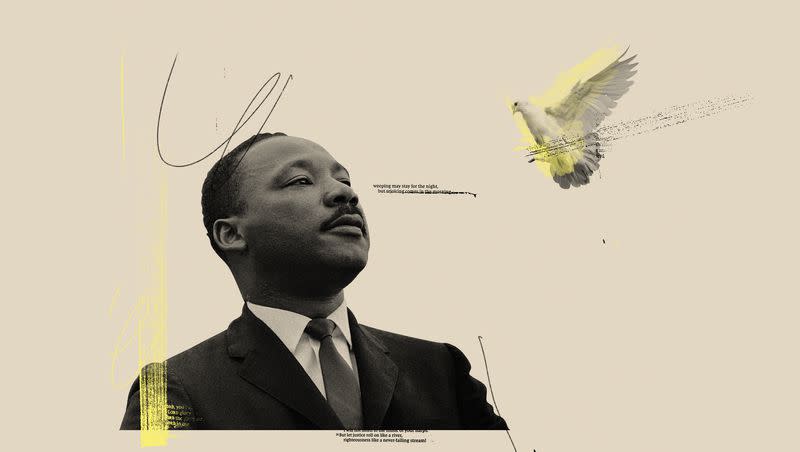

And like Jesus marching his cross toward his demise, King looked anguished. In an iconic photo from that march King strode beside Abernathy and Shuttlesworth, all three dressed down in denim shirts and jeans, but only two of the pastors smiling for the courage they embodied. King frowned. His eyes darted to the left, toward the camera’s lens, as if not wanting to see what faced him straight ahead.

Trouble.

Because here came a cop on a motorcycle, cutting hard in front of King on the street, forcing him to stop.

King dropped to his knees and began to pray. This is what the SCLC had taught all its protesters to do: If white authority is going to arrest you, let it do so while you remain on your knees, in prayer. I often wonder in that moment if King were offering more than a public display of nonviolence. I wonder if King were truly asking God for strength.

I tend to think he was. Because in the filmed footage of this encounter there is a moment that I always freeze, whenever I watch it online. The white cop has hoisted King off the ground and frog-marched him, roughly, to the waiting paddy wagon, when King briefly turns his eyes toward a television camera.

The eyes show everything.

They show fear. Nothing about this march has confirmed that God will reward King’s faith. King may be beaten in jail. The campaign here may die with him behind bars. The SCLC may no longer exist when he’s eventually released.

And yet in King’s turn toward the television camera his eyes also show hope. “You don’t have to see the whole staircase,” King later wrote. “You just have to take the first step.” His eyes showed how he believed that taking the first step, and then another, and marching would not lead to death but, somehow, a new life for the civil rights movement. King’s eyes showed the faith that, in some way, by some means he couldn’t imagine, God would see him through this.

And then he was beyond the camera’s frame and onto the Birmingham jail.

From here, the story becomes a bit supernatural. The solitary confinement of King’s imprisonment in Birmingham allowed for introspection, and in that “dungeon” of a cell, in King’s words, he used stubby pencils and scraps of newsprint to write a searing, soaring piece of rhetoric, a document that when it was finished not only compared to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation but carried the simplest of titles, as if only a simple heading could relay the letter’s transcendence.

“Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“God’s companionship does not stop at the door of a jail cell,” King later said of how he wrote it.

God’s companionship does not stop anywhere, it seems. King was sprung from jail after eight days thanks to his friend and fellow activist Harry Belafonte, the Hollywood actor who used his own fortune to release King and Abernathy and Shuttlesworth from jail on bond.

King’s freedom inspired a few, and then dozens, and then hundreds, and then thousands in Birmingham that spring to protest and march as King had. The jails filled with activists, and still more took their place on the streets, and white authority in Birmingham felt it had no choice but to release the K-9 corps again, to raise billy clubs high in the air and slam them on the heads of kneeling and defenseless Black protesters, to unfurl, even, fire hoses from the engines of Birmingham fire trucks and train the nozzles at Black children and then, with a water pressure whose power could knock bricks loose from their mortar or strip the bark from trees at a distance of 100 feet, to unload the water’s fury on the children, at 50 feet or less, and watch as it back-flipped the kids in the air and disintegrated the clothes from their bodies and pulled their hair from its roots.

And it was that pain, that filmed terror, the children’s suffering turned into a metaphor of the Black experience, which galvanized the Kennedy brothers. They saw the images of Birmingham from the White House and the president, and his brother as attorney general, ultimately saw what King did, too: The need for civil rights legislation.

This was that Easter season’s greatest miracle. President Kennedy’s sponsorship of civil rights legislation in June of 1963, just as King broke segregation in Birmingham, became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That miracle for King was followed by another: the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which further enshrined equality and led, I believe, not only to King’s martyrdom in 1968 but a new life for his country. Shirley Chisholm’s presidential bid in 1972, the rise of the Black middle- and then upper class across the closing decades of the 20th century, Barack Obama’s presidency at the outset of the 21st, even me marrying a Black woman in Texas, a former Jim Crow state, and now raising our kids on a shaded street where we are not harassed for who we are: None of this happens without the Birmingham campaign of 1963. And none of that happens without King returning to the two dozen in Room 30 on the morning of Good Friday, and saying to them that he had to “make a faith act.”

He had to march.

This moment marked the beginning of King’s “true leadership,” one of those present in Room 30 later said.

And this moment is the one I want my kids to remember well into adulthood, and what I want to return to myself when I’m uncertain, and you as well.

Just keep walking. Take the first step, as King said, and then another. Because when you are uncertain, God himself walks alongside you.

Adapted from forthcoming book, “You Have to be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live by Paul Kix, Celadon Books, a division of MacMillan Publishers.

This story appears in the April issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.