Before the Fall: Buster Murdaugh and the Witch Doctor Sheriff of Beaufort County

LOBECO, SC: NOV. 7, 1951 ― Harry Eugene Wilson stared into the eyes of his killers, and he knew them. He had known the young men and their family for years.

The 50-year-old shopkeeper and postmaster was a well-liked man, active in civic affairs. He worked with the Boy Scouts and was in the Exchange Club.

Wilson was also known to handle large amounts of cash. He ran a combination general store and post office in the rural farming community of Lobeco, about ten miles north of Beaufort on U.S. Highway 21.

He was totaling his receipts around 9:15 that Wednesday night when he heard a suspicious noise at the back of the store.

Wilson spun around and came face to face with his killer, who shot him in the face with a .22 caliber rifle.

The victim fell hard but did not die instantly. Wilson lay there in shock, as the two suspects ransacked his shop, taking cash, coins, and bonds.

The killers were on their way out the door when Wilson’s groans surprised them, and triggered the shooter, who went “berserk,” wrote a newspaper reporter the next day.

With the younger suspect keeping a lookout, the shooter bludgeoned his victim with the rifle stock until the weapon broke, and then stabbed Wilson repeatedly with an icepick until the pick broke off in the body, then beat him with a stick embedded with nails, before driving the stick like a stake into the victim’s ear and into his skull.

The pair fled the store, pockets stuffed with hundred-dollar bills, hands full of other loot. Wilson’s 13-year-old son, missing the intruders by mere minutes, found the grisly scene and the battered remains of his father and sounded the alarm.

It was a heinous crime that shocked and outraged coastal Beaufort County, but it was a case worthy of one of the best law enforcement officers and the fiercest prosecutor in the S.C. Lowcountry.

Welcome to the 14th Judicial Circuit

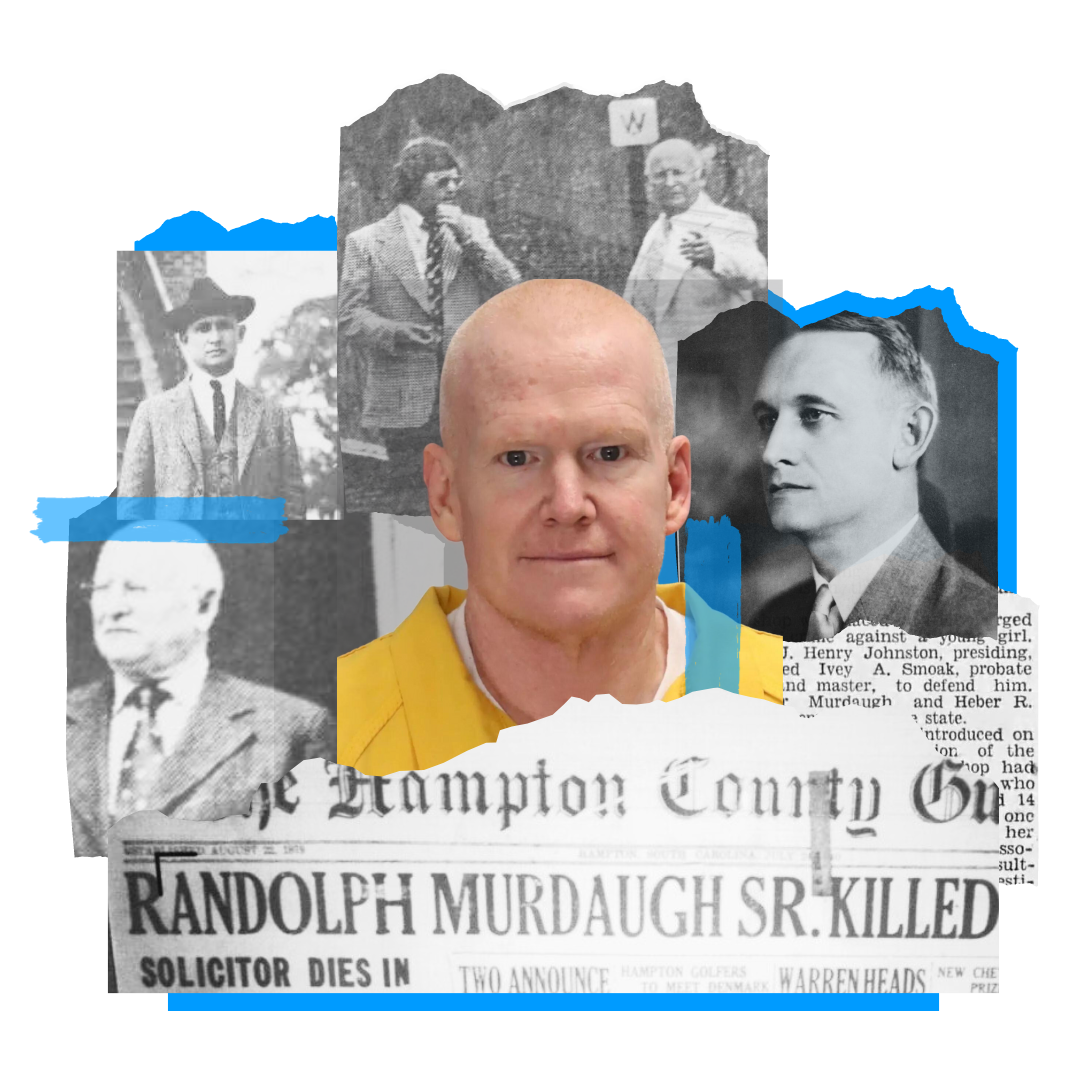

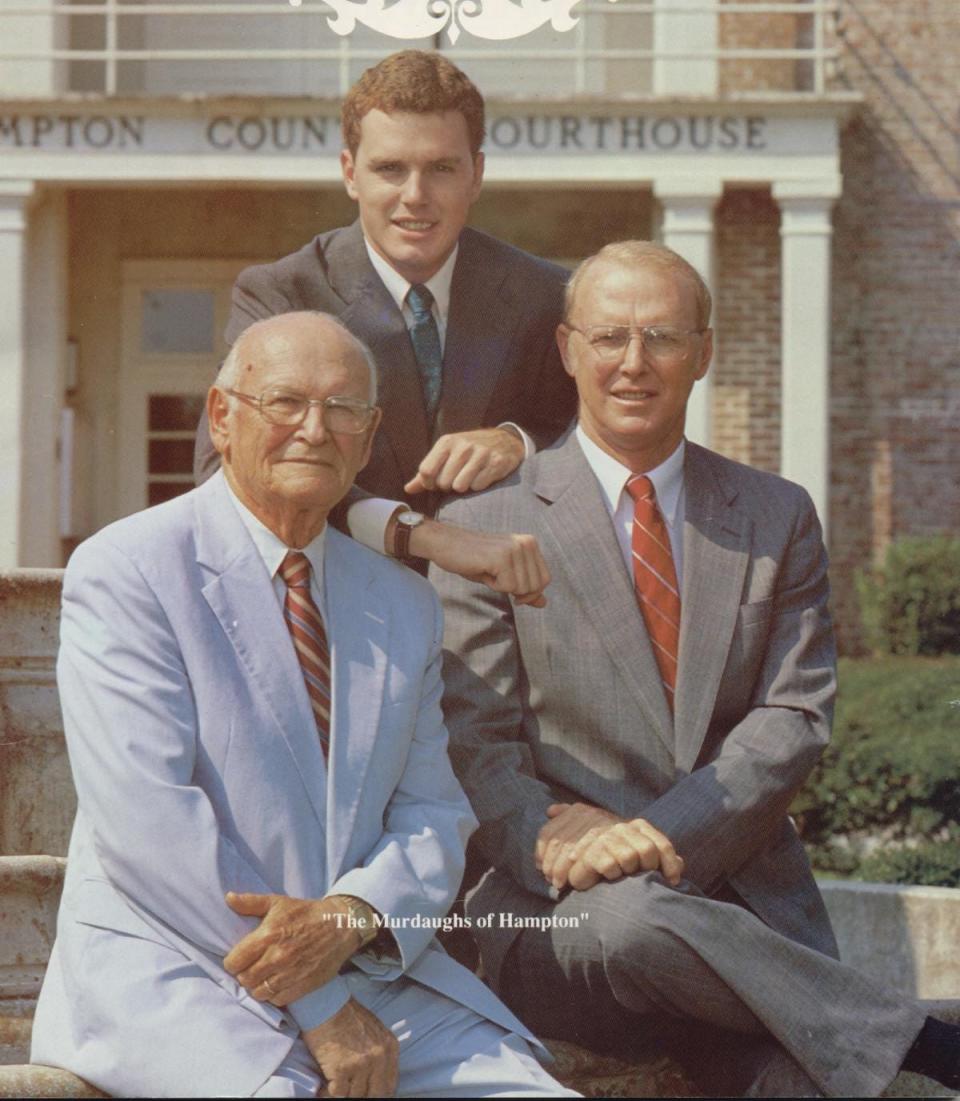

For nearly half a century, Randolph “Buster” Murdaugh Jr. was the chief prosecutor of the 14th Judicial Circuit, a mostly rural five-county legal district that harbored bootleggers, poachers, rum-runners – and the occasional heartless murderer.

Solicitor Buster Murdaugh was known as a hands-on prosecutor, often responding to crime scenes like the Lobeco killing and even assisting first-hand with investigations.

And while the Murdaugh clan of Hampton County has since made international headlines and become the stuff of historical legend after the recent double murder conviction and decade-long crime spree of Buster’s grandson Alex Murdaugh, the Murdaughs were by far not the only interesting personalities in the Lowcountry.

The 14th Judicial Circuit is a strange corner of coastal South Carolina populated with mysterious, colorful characters on both sides of the law.

Meet the 'Witch Doctor Sheriff' of Beaufort County

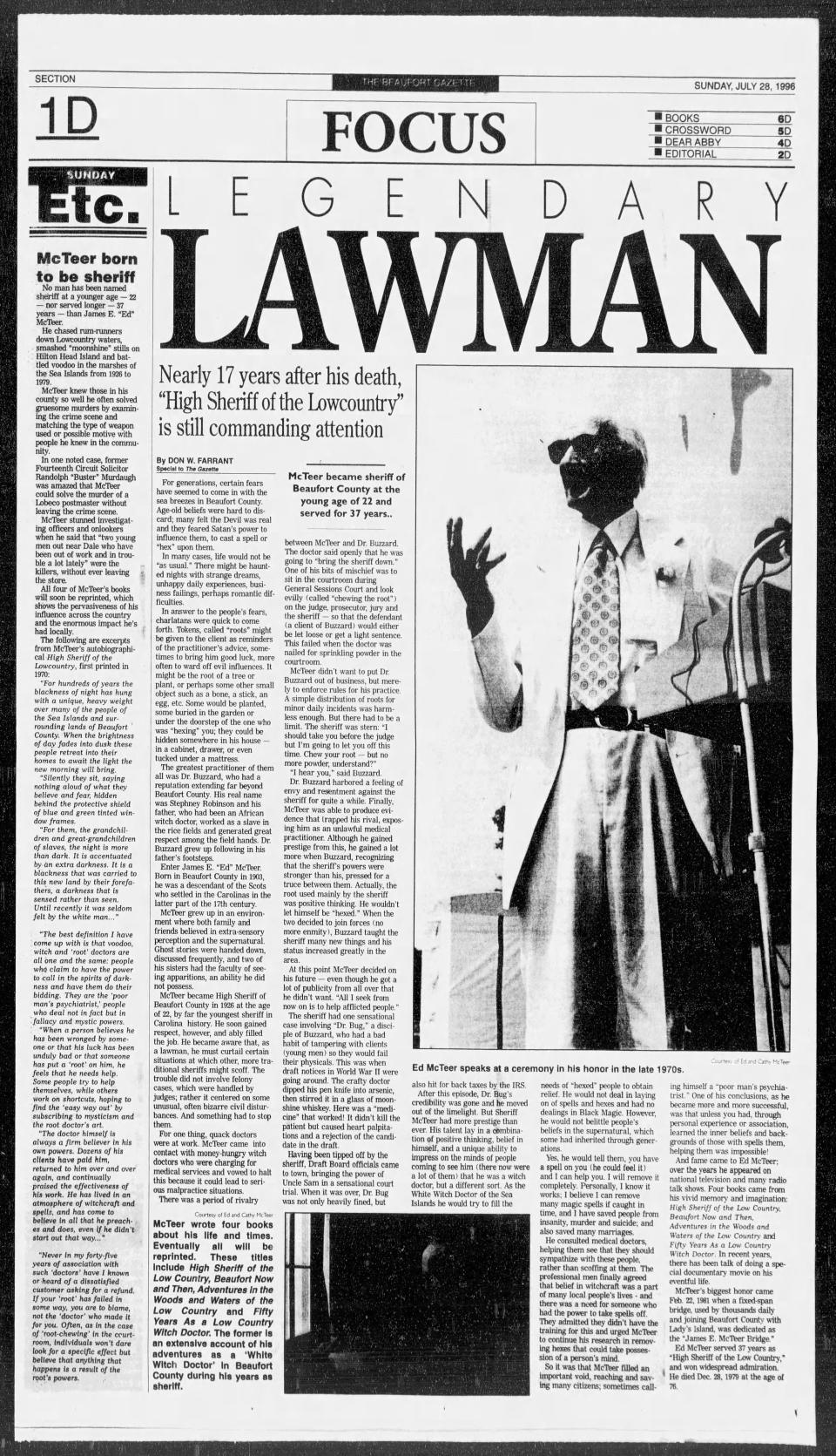

Meet James Edwin McTeer. Born in nearby Hardeeville in 1903, “Ed” McTeer became sheriff of Beaufort County on Feb. 11, 1926, at the age of 22 – by far the youngest sheriff in S.C. at the time, and some say in the nation – after his father, the previous sheriff, died in office and the S.C. governor appointed the son as a replacement.

After finishing his father’s unexpired term, McTeer was elected in his own right and served for roughly 37 years, until retirement in 1963.

But it wasn’t age that brought success and fame to the man some called “The High Sheriff of the Lowcountry,” or “The Witch Doctor Sheriff.”

A descendant of the Scots who settled the Carolinas in the 17th Century, McTeer grew up hearing the Old World legends and ghost stories in that superstitious era and spooky corner of the Lowcountry. His family and friends believed in the supernatural and extra-sensory perception, and two of his sisters claimed that they could see apparitions, a power McTeer did not claim to possess.

McTeer became a self-proclaimed “witch doctor” who studied the occult and hoodoo, as it is often called by the Gullah people of the Carolinas, for most of his life. Many of his constituents in Beaufort County believed in the old Gullah ways.

Once word spread of his benevolent brand of “white magic,” as he called it, locals attributed his success as a sheriff to those magical powers. And various incidents during his career helped reinforce that image.

After one incident, in which McTeer walked into a crime scene with no gun and survived a hail of gunfire to arrest a suspect, locals began talking and word grew that Sheriff McTeer did indeed have supernatural powers — a legend the sheriff did not discourage.

The legend also holds that, in all of his years as sheriff, he never carried a gun but relied on his powers as a hoodoo witch doctor to protect him and help identify and track down criminals.

In addition to enforcing the Prohibition laws of the era and solving grisly, often mysterious murders like that of Postmaster Wilson, McTeer helped with other unusual cases, such as a string of grave desecrations in the area many believed were linked to voodoo worship, and he often went after rival witch doctors for using their powers in nefarious, often harmful ways.

To learn more about McTeer’s rivals Dr. Buzzard, Dr. Bug, and others, check out Episode 15 of the author's Wicked South Podcast.

Before the Fall: The Murdaugh Solicitor files - A scandalous case of a pedophile preacher

Murdaugh and McTeer team up on moonshine cases

Like McTeer, Buster Murdaugh Jr. was appointed to fill his father’s unexpired term as solicitor when Murdaugh Sr. was killed in a car-versus-train accident in 1940, and like McTeer, Buster Murdaugh was highly popular and remained in office for decades.

Buster Murdaugh took office as the 14th Circuit Solicitor in 1940, after McTeer was well versed and experienced in his duties as sheriff, and the two worked together for more than 20 years.

The bulk of the cases they investigated and prosecuted together involved thefts, assaults, and of course, illegal liquor.

In addition to backwoods “moonshine stills” operated by locals, there was an organized crime element in that Prohibition era that worked to import large quantities of contraband booze into the coastal areas. Beaufort County, with its hundreds of islands and miles of rivers and creeks was a perfect point of entry for smugglers and rum-runners from the Caribbean and other places.

McTeer became known for his ability to sneak into the marshy swamps and nab the smugglers, and once they were brought to justice, Murdaugh made swift work of prosecuting them.

But local murders often proved more troublesome. When McTeer took office, he immediately proved to be a dogged investigator, working cold murder cases that happened during his father’s tenure.

He once arrested a murderer roughly 20 years after the crime – when the man came out of hiding in another state to apply for his World War I veteran benefits. He arrested another man on Hilton Head Island 40 years after the suspect killed a magistrate’s constable.

McTeer knew Beaufort County and its people so well, he claimed, that he could examine a crime scene and match the type of weapon or possible motive with people he knew in the community.

“He had an innate ability to solve a crime,” Murdaugh once told the press. “He could tell you who killed a person back in the old days just as soon as he got to the scene.”

The Lobeco Postmaster killing: the ‘most brutal’ ever seen

When Sheriff McTeer got word that the Lobeco Postmaster Harry E. Wilson had been robbed and brutally beaten at his store in Lobeco, he and his men quickly responded.

The murder was shockingly violent. The victim’s head had been clubbed beyond recognition, and a sharp, pointed stick had been forced into his ear opening. The body also had 29 ice pick stab wounds, including one in which the ice pick broke off in the victim’s spine and became embedded there. It was described by physicians and the coroner as the most brutal slaying they had ever seen.

The postmaster had been beaten with the stock of a .22 caliber rifle. The wooden stock was still at the crime scene, but the barrel of the weapon was missing.

Sheriff McTeer notified Solicitor Murdaugh the night of the killing, and the solicitor arrived at daylight the next day as police began the investigation. McTeer recalled the case vividly in his book, High Sheriff of the Lowcountry.

McTeer, after surveying the crime scene, stunned Murdaugh, his fellow officers, and onlookers when he appeared to quickly crack the case and identify the killers, saying that “Two young men out near Dale who have been out of work and in trouble a lot lately” were the killers.

McTeer quickly pulled Buster off to the side. “Randolph, I believe I know who the killers are,” and he told the solicitor about the troublesome Priester boys in the nearby Dale community who had been getting into drunken trouble at local juke joints.

“You must be joking,” Buster replied. The sheriff had not left the crime scene to check for footprints, nor had he searched for or interviewed any eyewitnesses, taken fingerprints, tried to match the weapons or any of the other usual investigative techniques.

“Ed, you know the county and your people,” Buster added, “But I don’t think this one can be solved without leaving the store.”

McTeer insisted that his hunch was correct, and the solicitor wrote the suspects’ names down, J.P. Priester and John Priester, and the manhunt was on.

Beaufort County officers were quickly joined by state police, wildlife officers, the highway patrol, and even agents of the postal service. The posse began following the suspects’ trail east and quickly found the bloody rifle barrel, discarded in the woods. In a nearby swamp, they found ashes where bonds and other evidence had been burned.

The trail led them to the Priester residence, and then on to the main highway where the suspects made their getaway.

Upon arriving at the suspects’ mother’s home, officers were told the boys weren’t around – but after questioning they learned that a .22 rifle could not be located and an ice pick was missing from the ice box.

State police in Georgia were notified, and the hunt continued across state lines. The trail led investigators to a used car lot in Savannah, where they were told the suspects had put cash down on two cars.

Roughly 48 hours from the time of the killing, the brothers were located and arrested by S.C. and Georgia officers at a county fair in Savannah, Georgia, where they had been spending one-hundred-dollar bills stained with the postmaster’s blood.

Solicitor Murdaugh and Sheriff McTeer made a speedy trip over the Savannah River to help officers extradite the suspects to Beaufort County.

The suspects told McTeer and Murdaugh the horrid details. The robbery had been planned a week before when the brothers called the car dealer in Savannah. J.P. did the killing and maiming, while John was the lookout. They even led police back to the swamp, where they had hidden a bag of coins and valuables in a hollow tree.

Once in custody and confessing, the suspects were sent to Columbia for “their own protection” from an outraged community.

The accused were given two public defenders, Buster Murdaugh was the prosecutor, and after a short trial in the March 1952 term of General Sessions in Beaufort County, during which their confessions were brought into evidence, they were both convicted.

When the judge asked if they had any words prior to sentencing, J.P., in a barely audible voice, responded that because they had told the truth when arrested they deserved mercy.

Mercy was not to be found, and both were sentenced to die in the electric chair. There was little emotion in the crowded courtroom, according to newspaper reports of the day. The Priesters’ relatives were allowed to speak to them only briefly, and then they were transported to the state penitentiary in Columbia.

Less than a month later, in April, the brothers were transported to the “Death House,” The State newspaper reported, to await death by electrocution. McTeer told the press that his desk was stacked with applications from county residents who wanted to witness the executions.

The execution date was set for April 18, and there were so many would-be spectators from Beaufort County that officials limited seating in the room to 40 witnesses per electrocution.

One by one, John, 20 and never married, and J.P., 27 and married, were strapped into the electric chair. When asked if they had any last words, John admitted that “fooling around with whiskey and juke joints” put him where he was.

When asked what he would like to say, J.P., who had confessed to personally doing the killing, replied, “Nothing at all.”

The State paper noted that it was the first time in several years that more than one person was executed by the State of South Carolina on the same day.

The brothers’ bodies were claimed by their parents and were buried in their family’s plot at Mt. Carmel Baptist Church in Dale, over the protests of many church members in the congregation.

High Sheriff long remembered in the 14th Circuit

Even after his retirement and death, McTeer’s legendary status lived on.

“He chased rum-runners down Lowcountry waters, smashed ‘moonshine’ stills on Hilton Head Island and battled voodoo in the marshes of the Sea Islands from 1926 until [his death in] 1979,” the Beaufort Gazette wrote in tribute on July 28, 1996.

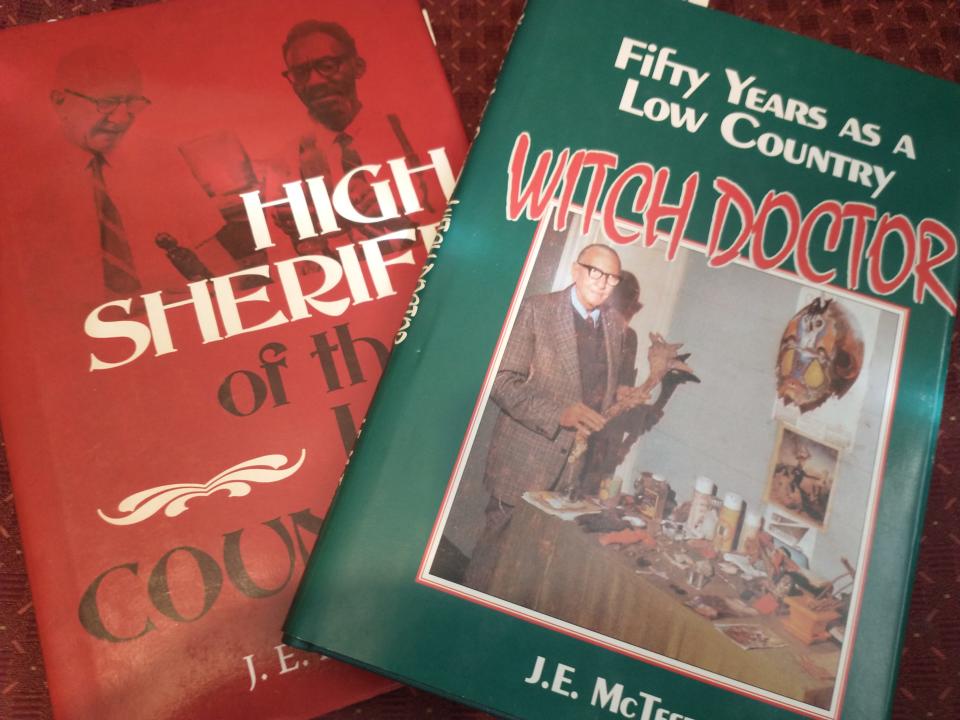

Noted as a lawman, and as a root doctor McTeer became famous for allegedly using his powers to fight crime, and for his ability to remove evil “roots,” hexes or curses from his superstitious constituents. He would go on to write four books, including Fifty Years a Lowcountry Witch Doctor, and made appearances on numerous radio shows and national television programs.

McTeer’s greatest honor came on Feb. 22, 1961, when a new bridge joining Beaufort and Lady’s Island was named the “James E. McTeer Bridge” in his honor.

McTeer died Dec. 28, 1979, at the age of 76. Even as his legend as a lawman, witch doctor and author prevailed, his grandson, James E. McTeer II, won the 2015 South Carolina First Novel Prize for his novel, Minnow.

To hear more about the Witch Doctor Sheriff of Beaufort County, check out the latest episode of The Wicked South Podcast.

Follow Michael DeWitt's reporting as The Hampton County Guardian/Greenville News and the USA Today Network continue to follow cases related to the Murdaugh crime saga. Follow DeWitt on Facebook and on Twitter at @mmdewittjr for the latest updates.

This article originally appeared on Augusta Chronicle: Buster Murdaugh and the Witch Doctor Sheriff of Beaufort County SC