When Fall River rides heat waves, the Flint feels the worst effects with little relief

FALL RIVER — Near midday on a bright, sweltering Sunday, one side of Pleasant Street in the Flint neighborhood was shaded by buildings. The other received the full brunt of the sun’s power. On either side, the temperature was unbearable.

A recent study by an urban planning firm found that 75% of the Flint is impervious surface: tar, concrete, cement, stone and brick. Green space, when it exists, is small, and though there are three or four trees lining Pleasant Street, they're not large or leafy enough to provide any meaningful shade. These are the perfect conditions for a “heat island.”

Heat islands, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, are urbanized areas that experience higher temperatures than the outlying areas. They're places that are densely packed with streets and buildings and other surfaces that absorb and re-emit heat, driving up the air temperature to several degrees higher than areas with more green space. It can make living in these areas much more uncomfortable, more costly, and even more harmful.

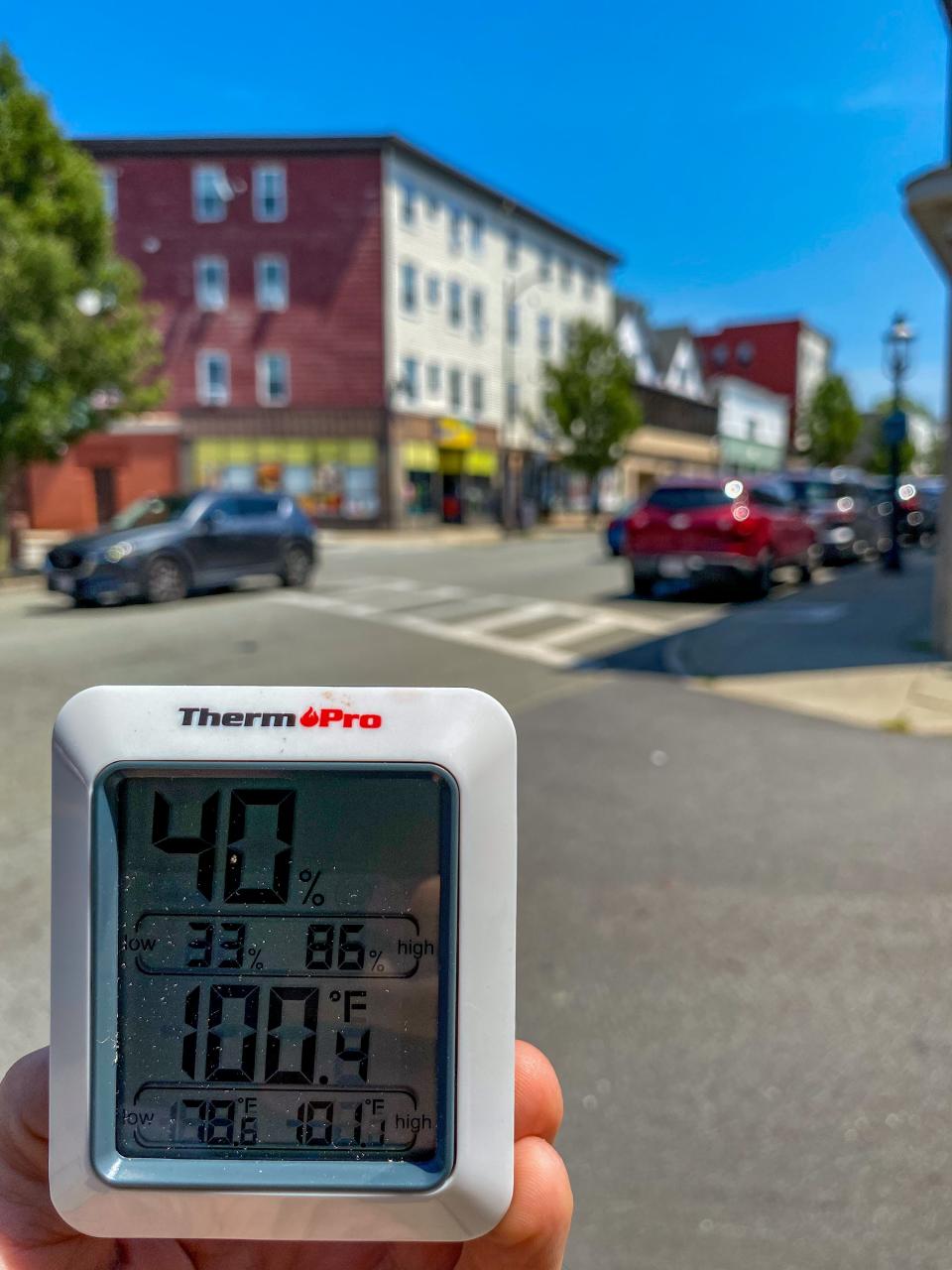

The Flint is one such heat island. On a recent Sunday during a heat wave, when the weather was already at a high of 91 degrees with a 14 mph breeze, the densely packed neighborhood felt even more stifling. The breeze was only light, blocked by the buildings on either side; a reading of the air temperature read 100.4 degrees.

Can't beat the heat: We created scorching 'heat islands' in East Coast cities. Now they're becoming unlivable

Taking the temperature of Greater Fall River

A USA Today Network reporting project called “Perilous Course” looked at heat islands, with journalists from more than 30 newsrooms from New Hampshire to Florida looking into the real-life affects, digging into the science and investigating government response, or lack of it.

Climate change has exacerbated the intensity of heat waves, the number of excessive heat days per year and the length of these heat waves. The average length of a heat wave season in 50 big cities studied is now around 70 days, compared to 20 days back in the 1960s. In less than one lifetime, the heat wave season has tripled.

Development in Swansea: A Kraft Group company, new gym, repaved road: The Shoppes at Swansea is taking shape

In Fall River, the middle of July has been abnormally hot and dry, with temperatures regularly in the upper 80s to mid-90s. The city has been facing moderate drought conditions along with most of the rest of Massachusetts.

Still, some areas of the city are hotter than others, as measured in an informal survey around midday to early afternoon on July 24, with predicted temperatures at 91:

In the neighborhood of Highland and Lincoln avenues, some of the city’s priciest real estate can be found. Though Highland Avenue is a wide stretch of tar and retains heat, properties in the area feature expansive lawns and the street is partially shaded by towering trees many decades old. A cool breeze rides uphill from the Taunton River. Air temperature: 95.9 degrees in full sun.

At Freelove and David streets, in the suburban enclave east of Eastern Avenue, homes are smaller, spaced with large lawns and trees that overhang the road and protect it from absorbing the sun. A steady breeze keeps the area feeling cool. Air temperature: 93.6F in partial shade.

Lawton Park, downtown on the corner of South Main and Anawan streets, is fully shaded by a cluster of trees and the buildings nearby. It’s paved entirely with brick, but the shade keeps the stone cool, and the breeze is fuller. Air temperature: 94.5 in full shade.

At Fall River’s waterfront boardwalk near the boating center, the wind is cooling off the river but the air feels hotter as sun reflects off the surface with a shimmering hot parking lot and several lanes of highway at its back. Air temperature: 97.3 in direct sun.

In Somerset at Riverside Avenue and Harrington Lane, the properties feature large lawns to absorb heat with trees providing some shade. Air temperature: 92.7 in direct sun.

Of the areas surveyed, the Flint was tied for hottest, along with one other: the center of the South Coast Marketplace parking lot, a steaming hot stretch of tar packed with cars and featuring no shade. Air temperature: 100.4.

Turning up the heat: Biden talks climate emergency in a politically divided Somerset

Why heat islands matter, and why some residents need help

Extreme heat is not only uncomfortable — it can be dangerous for the elderly and those with medical conditions. In a large-scale study that examined heat in 43 countries, including the U.S., researchers found that 37% of heat-related deaths could be attributed to the climate crisis.

It’s especially dangerous for those in the Northeastern United States.

“What becomes really dangerous in these more northern cities is that they haven't yet adopted air conditioning very widely yet,” Jeremy Hoffman, the David and Jane Cohn Scientist at the Science Museum of Virginia. said. “And especially in lower income and communities of color or immigrant communities, prevalence of air conditioning utilization is very low.”

Real estate report: Fire-damaged Fall River multi-family fixed, resold after 'as-is' sale

In the area of the Flint surveyed, the median household income is less than $26,000 a year — the state median household income is over $84,000. A third of the population in this area are people of color, and multi-family housing is the primary housing stock here. Assuming residents can afford to buy, transport, store and install an air conditioner, the cost to run it might be prohibitive.

The median energy burden — the percentage of income spent on home energy costs — for low-income families is 8.1%, while the national median is 3.1%, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

In Fall River, Citizens For Citizens Inc. administers the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which in Massachusetts helps low-income people pay heating bills during the frigid winter months. It’s a blessing for people who struggle to afford to stay warm in long New England winters. But for now, CFC’s Dennis Medeiros said, the program doesn’t yet offer any help with cooling in excessively hot weather.

The closest thing available, Medeiros said, is if clients have extra heating assistance funds left over at the end of the cold season.

“We do pay clients heating bills from ... November to April 30. If they have any remaining money left over from whatever their award was, over the years, given that permission from the state, we are allowed to make a secondary payment on their electric bill, assuming they don’t heat with electric,” Medeiros said. “But that’s usually a smaller portion, and that kind of follows the same time frame.”

President Joe Biden recently announced a series of measures related to climate change during his recent visit to Somerset, and one of them was expanding LIHEAP to cover cooling costs as well. But it’s unclear if Biden's announcement has made it past the planning stage into providing actual money to people who need it. It's also not clear if it would be available in all states, or when such a plan might begin. If that money is available now, Medeiros said, he hasn’t been made aware of it.

“That doesn’t mean that's not happening, but as far as I know, I have not heard anything about that yet,” Medeiros said.

If a LIHEAP expansion comes to fruition, CFC would be the agency to distribute those funds as well.

“We try to do everything we possibly can to help in any aspect, if we’re allowed to,” Medeiros said.

USA Today Network reporters Joyce Chu, Eduardo Cuevas, Eduardo Aguilar and Ashley R. Williams contributed material to this story.

Dan Medeiros can be reached at dmedeiros@heraldnews.com. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Climate change, 'heat island' effect hits Fall River's Flint hardest