Falling hard for fungi. It's that time to eat and learn what the woods have to offer

It's possible to imagine Bruno Iacovone and Deana Tempest Thomas unknowingly searching the same woods on a brilliant autumn day and gazing so hard at the next decomposing stump, or the base of those old oaks, that they'd miss the other passing treasure hunter.

Mushrooms have that effect on them.

For different reasons.

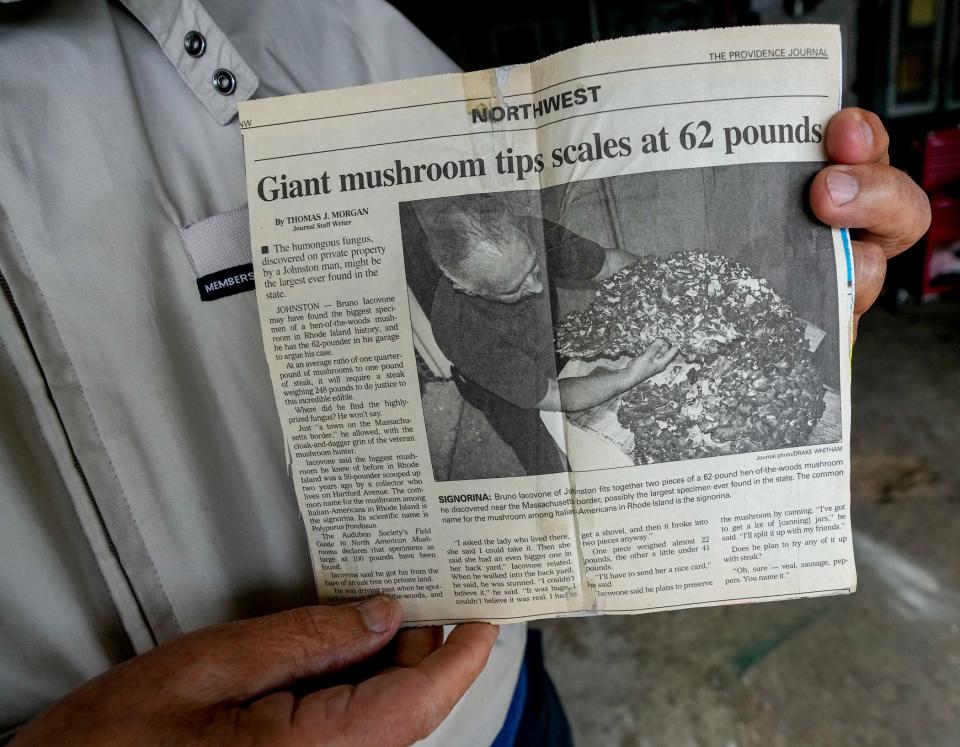

“When I find a big one, I talk to them,” lovingly, confesses Iacovone, 83, of Johnston. His 1998 discovery of one of the biggest local specimens of the prized hen of the woods – possibly the biggest, at 62 pounds – still garners him foraging acclaim.

“My wife, she’s jealous,” he says, chuckling, of wife Domenica's reaction to his mycological flirtations. “I’m sick. What can I do?”

(Keep reading for the untold story of where he found that delicious accompaniment to any steak.)

'Any moment something exciting could be discovered'

Tempest Thomas, who lives in Scituate and is half Iacovone’s age, has fallen equally hard for fungi.

So much so that she left her job as an emergency room technician three years ago, bought the small farm she grew up on and began to immerse herself in the mysteries of mushrooms.

She’s not hunting for side dishes, a time-honored Rhode Island tradition this time of year. She wants to bring more scientific awareness to an often disrespected and undervalued part of nature.

“Oh my God, it’s an obsession” now, says Tempest Thomas, who started the Rhode Island Mycological Society. “Head over heels in love with them. You never know what you’re going to find when you’re out there. Any moment something exciting could be discovered.”

Like the discovery of the rare Billie’s Bolete earlier this month by fifth-grader Silas Claypool, of Barrington. The species had only been documented in Rhode Island a handful of times, said Tempest Thomas.

The fact that word of Silas’ discovery spread quickly through the local mycological community like puffball spores in the wind speaks to how interest in mushrooms has bloomed with the internet and social media.

“I think mushroom clubs have grown in popularity because information is more accessible, and people are finding out about them," says Tempest Thomas. "Before, it was, 'Where do I go to learn about mushrooms?’ Unless you knew someone, it was hard to figure it out.”

Brighter spotlight on a shadowy species

Mushrooms are indeed having a moment.

The 2019 documentary hit "Fantastic Fungi," with its time-lapse photography of emerging mushrooms and coils of strange fungi, drew viewers into a little-understood world.

And online identifying competitions, like the Northeast Rare Fungi Challenge, now underway, help scientists and conservationists gather data about rare or underdocumented fungal species.

Not to mention “it’s just fun,” says Tempest Thomas. “It’s like crossword puzzles for other people.”

In Europe, countries are realizing that with habitat loss, some mushroom species are going extinct, Tempest Thomas says. "They are putting some conservation plans in place over there. I think it is only a matter of time before our country catches on."

Why mushrooms are important 'ecosystem engines'

Tempest Thomas says she has identified and logged “only” 538 species of fungi for the online site inaturalist. “Only,” she says, because there are more than a million known species out there.

“Our understanding of the fungi kingdom has been greatly lacking,” she says. Children are only taught to fear mushrooms, because many of them are poisonous, which is true. But “there is really so much more to them. They are ecosystem engines. Without them, a lot of plants can’t survive.”

For Iacovone, like many other traditional foragers, it is what's edible out there this time of year that has his attention.

And there is nothing more delicious, he says, than his primary quest: what's commonly known as hen of the woods or, as he and many other older Italian-Americans call them, signorina.

How to find a hen of the woods

The hen doesn’t look like a typical mushroom. It grows in roundish clumps at the base of old hardwoods, usually oaks. It earned its name because it resembles a brooding hen, with its overlapping layers of brown or gray caps that look like plumage.

Served at trendy restaurants, it is an easily identifiable mushroom that often sprouts from the same tree over several years. Hunters like Iacovone guard their hen trees with secrecy.

Ask to go along as he hunts for them and the answer is predictable:

“No, you can't come” he says flatly. “I don’t even tell my wife where I’m going.”

Average hens weigh between 2 and 14 pounds. And often they will be right there in people’s yards, seemingly unnoticed by all except a seasoned forager.

“Every time my wife and I are driving around, she gets mad because I can spot one from a half-mile away, almost. She’ll say, ‘You got enough signorina. Let it go.”

Iacovone says he’s harvested about 100 hens so far this season. He gives most of them away to his friends. What he doesn’t give away he cans for long winter days when he can pop the seal and recall his successful hunts.

How a mushroom lover won the 'signorina' of his dreams

Which brings us to that once-in-a-lifetime find of 25 years ago.

Iacovone has told the story hundreds of times to friends and family. The story made it into The Journal at the time, but he didn't give many clues then as to where he'd found it. The closest he would say was that it was "in a town on the Massachusetts border," with the presumption being it was a Rhode Island-foraged hen.

Well, that wasn't actually the case.

It was months before the hen season would begin, and the Iacovones were taking a drive by the La Salette Shrine in Attleboro, Massachusetts.

Along the way, they cut through a neighborhood in North Attleboro with what looked like a promising stand of old oaks. Iacovone made a mental note: He’d come back here when the signorinas started popping.

And so there he was in October 1998, parked outside a house and looking at "a nice 14–15-pound signorina right there in front of the North Attleboro house.”

He knocked on the door: “Good morning,” he said. He introduced himself. “I said, 'You have something in your yard if you have no use for, I’d appreciate it if I can have it.’ She said, 'Like what?'”

He explained what was growing at the base of her oak tree.

“’Oh yeah, you can have it,’ she says to me. Then she says, ‘I have a huge one in my backyard.’ I said 'Oh yeah? Would it be OK if I looked at it?’”

When Iacovone went around the corner and saw that big, beautiful signoria – the equivalent of an open chest of gold for a mushroom forager, “I became like a kindergarten boy."

“I just was paralyzed. It was so big. I didn’t know where to begin to pick it up. I didn’t want to break it. It looked so pretty. I said, ‘Oh my God, you are one pretty mushroom. So I’m gonna cut nice and slow, nice and gentle.'”

“For some reason, if I were romantic to a woman like I’m romantic with the signorina, I would be Casanova.”

Contact Tom Mooney at: tmooney@providencejournal.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Peak season for mushroom foraging in RI