The false narrative of 'the narrative'

Just under a year from midterm elections that look likely to wrest control of Congress away from the Democrats, leading members of the party claim to have discovered the source of their troubles. In the words of New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, quoted in The Washington Post, "it's just a fact" that "Democrats are terrible at messaging."

The Post piece treats that assertion as a given and goes on to quote several Democratic bigwigs saying much the same thing. All agree that the party has yet to hit on a message to sell its legislative achievements and reverse the slide in President Biden's approval numbers that began in late July.

But is that true? Are Democrats merely a victim of their own messaging ineptitude? Is Biden's unpopularity attributable to media insistence on hyping inflation and other bad news at the expense of all the good things his party has been doing for average Americans? It's easy to see why Democrats would like this narrative about "the narrative," but the explanation doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

Pointing to a messaging problem is a perennial temptation for modern politicians. If you found yourself friendless, would you prefer to believe your plight was a result of your unappealing habits and personality? Or that people had just been misinformed about you? The answer is obvious, and it explains in psychological terms why faulty messaging so often takes the blame for falling approval numbers.

But focusing on messaging is also appealing because it affixes blame to process instead of substance. Hiring a new comms team is much simpler and less painful in terms of coalitional politics than abandoning or reshaping an entire policy agenda. It's also much less risky than attempting to own up to and repudiate past mistakes. Rather than undertaking a major change of direction, the party can assume everything would be going better if only the voters were better informed.

Yet messaging is rarely the primary problem — and it certainly isn't when it comes to the Democratic Party's current troubles. Those difficulties are rooted, first and foremost, in a disconnect between the sweeping ambition of the party's progressive wing and the Democrats' failure to win bigger congressional majorities in the election last year. The progressives want a New New Deal or a Greater Society with margins in Congress vastly smaller than Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson enjoyed when they launched their bold policy programs. This has led to months of slow, grinding negotiations between competing factions in a sharply divided Democratic Party, where nearly every vote is required for passage of legislation.

That certainly hasn't helped Biden or his party. But has it hurt? It's hard to say, since it's unclear that anything could forestall a wipeout a year from now. The party that controls the White House nearly always loses seats in midterm elections — and both houses of Congress are so narrowly divided that just about any losses at all will hand control to Republicans.

But Democratic woes aren't just a function of what data analysts call "thermostatic public opinion" (the structural tendency for public opinion to rise and fall like the tides relative to the country's four-year election cycle). It was reasonable for the Biden administration to assume the president would enjoy an approval boost in the wake of the $1.9 trillion COVID Relief Package that was signed into law in March. But it didn't happen. There has likewise been no polling bump from passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill two weeks ago.

This is where the "messaging" critique comes in, with leading members of the party and progressive activists alike insisting that lack of a polling bounce is a function of the party losing control of the narrative. But is it really plausible voters didn't notice extra money magically appearing every month in their bank accounts after passage of the COVID relief package? It's hard to imagine a communications strategy that could reach more people and inspire better feeling than hundreds of additional dollars automatically showing up in the pockets of tens of millions of voters.

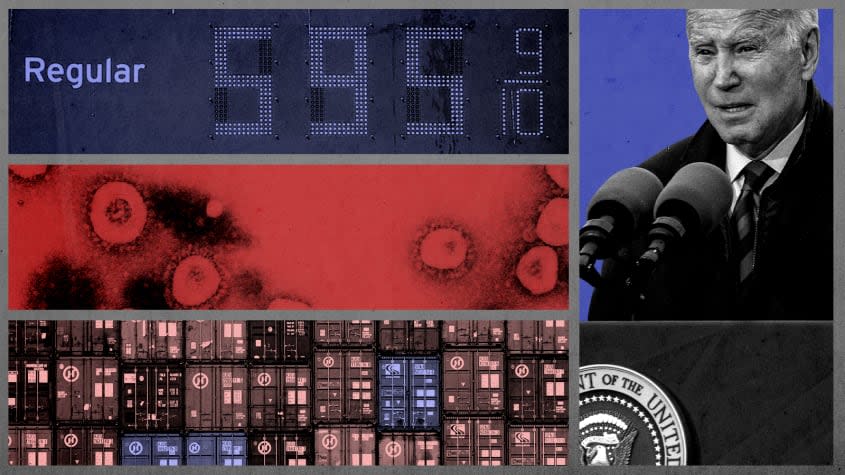

Maybe Democrats should consider that this money — like the provisions of the infrastructure bill that was recently passed and signed — didn't address the things voters say they're worried about, including inflation, supply-chain disruptions, and the persistence of the pandemic.

Now, some observers on the left insist people are mainly worried about these issues because the media incessantly hypes stories of price hikes, delayed deliveries, and ominous-sounding new variants of COVID-19. It's certainly true that journalists write a lot about these topics. But it's also true that most people can sense inflation is on the rise by noticing a spike in prices at the gas station and grocery store, just as they can see the bare shelves at Walmart and Target for themselves and notice when they're told that a Christmas gift they've ordered online won't arrive until the third week of February. As for the pandemic, nearly two years is a very long time to be living with low-grade anxiety about health and an ever-changing amalgam of rules and restrictions with no clear end in sight.

The world in late 2021 feels vaguely broken — and the response of the president and his party has been to ... work for more than six months on passing a pair of spending bills packed with items that have been languishing on Democratic wish lists since the closing years of the Obama administration.

There's nothing explicitly wrong with any of it. But neither does it feel especially responsive to the problems of the present. Because it isn't.

The president and members of Congress can come up with a million and one ways to communicate their wonderfulness to the electorate. But so long as voters don't sense that the party is working to address the dysfunction that seems to be closing in on all sides, Democrats will find themselves struggling to hold their own — and fending off a potential calamity a year from now. The party's problems go well beyond communications, and no narrative can override daily life.

You may also like

7 scathingly funny cartoons about Thanksgiving inflation

Matthew McConaughey says he won't run for Texas governor 'at this moment'