Families still need care, but many are afraid of nursing homes amid the coronavirus pandemic

Marianne Parker picked up her older brother from St. Louis in early March for what she thought would be a short visit to her home.

The 64-year-old retired educator and entrepreneur had spent months finding a new living and care situation for her nomadic brother, who suffered from dementia after a massive stroke last fall in Florida. Parker’s plan included a long-term care facility near her home in Quincy, Illinois.

Then the coronavirus pandemic changed everything.

Bureaucratic delays and state lockdown orders kept the siblings confined to Parker’s small house. And fears of COVID-19 had Parker contemplating keeping her brother, John Boyce, with her at home.

But then, days apart in late April, Boyce suffered a sudden cognitive decline and Parker injured her back. Both were hospitalized, and doctors told Parker she had only one choice for her brother’s care: a nursing home.

“It was an excruciating decision and it's even more excruciating with the restrictions of COVID-19,” Parker said.

Across the country, families like Parker’s are struggling with what to do about long-term care for loved ones who need specialized attention.

Months into the coronavirus pandemic have cemented the reality that nursing homes can be one of the most ripe and deadly settings for an outbreak. And what can already be a murky and frustrating web of healthcare choices, cost barriers and quality issues is now overlaid with a deepening fear and worry about safety.

More than 16,000 residents and staff of long-term care facilities have died from COVID-19, according to data officials released earlier this month after mounting public pressure.

The AARP told USA TODAY that as of this week, it has fielded direct inquiries from nearly 4,000 families since the pandemic began on what to do about long-term care, which it said is causing “high anxiety.” Virtual town halls on the topic have drawn more than 50,000 participants each.

“People are understandably very wary about how to provide long-term care for their loved ones that need it, or even for themselves,” said Lori Smetanka, executive director of National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, a nonprofit advocacy organization. “What we're seeing in nursing homes is really causing, frankly, all of us as a society to rethink what our long-term care system looks like.”

More than 1.3 million people live in nursing homes nationwide, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The country's long-term care system, patient advocates say, is too expensive for most people, limits choice and varies wildly in terms of quality. Within America’s fragmented health system, nursing homes also are used as rehabilitation centers for people who have had strokes or heart attacks or elective surgeries.

Marjorie Moore is executive director of VOYCE, which implements a long-term care facility ombudsman program in the St. Louis metro area and northeast Missouri region up to the Iowa border. The organization covers more than 300 long-term care facilities.

Moore said there’s been an uptick in calls from confused families as the pandemic has unfolded.

Some say their loved ones have been discharged improperly from hospitals or from facilities. In the early days of the pandemic, she said, people also pulled their relatives from facilities only to find out later that it was too overwhelming to care for them at home. Others still are seeking guidance about whether to put someone in a nursing home.

”We know that facilities are trying hard. We know that there are some bad actors in those facilities. We know that there's people that are overworked and tired,” Moore said. “People have always been afraid of putting a loved one in a nursing home, you know, and so that's not new. But I think the problems nursing homes have had for years were made more apparent to the public because of this pandemic.”

Navigating long-term care options not easy, but there's help

Parker got a crash course in navigating the long-term care system late last year once it was clear Boyce, 65, was permanently changed by the stroke. The family agonized what to do next. Parker and her brother had only sporadic contact in the past four decades.

“I mean, I really don't know this man. I think he's an interesting man. But it's not a brotherly thing,” she said. “It's just that, by gosh, a person essentially lost their brain overnight. Overnight. Completely lost their independence. And then it just seemed like the natural thing to do, that this person needs an advocate.“

But her brother was uninsured. And it was incumbent on the family to figure out how to pay for long-term care.

The learning curve was steep.

Parker didn’t know Medicare didn’t pay for nursing homes, and she had to figure out how to get her brother signed up for Medicaid.

She wanted to put him somewhere that specialized in memory care, but those are often private-pay. Some places cost upwards of $20,000 a month.

“It didn't take long for me to come up with a theory that the really wealthy people in this country got together at a country club and decided, ‘You know what? We're getting old. We're getting dementia. And we really don't want to go live with all these other people. We need to build places of our own so that we can live, you know, with it in the manner in which we're accustomed,'” Parker said. “And I don't really mean that sarcastically.”

Parker says she sometimes spent 10 hours a day trying to figure out options. She eventually found a long-term facility that specialized in memory care and recently started accepting low-income patients under Medicaid.

“It's just been a very, very long journey. It was literally a full-time job. Phone calls, interviews, going to Social Security, going to Medicare, going to Medicaid, being interviewed, seeing lawyers,” she said. “It shouldn't be this hard. And I don't say that on my behalf. It shouldn't be this hard for anyone to speak for the voiceless. “

Experts say it is hard, but there is help.

“Most families, when they're going through things, they tend to start going it alone because they don't realize that a lot of other folks have been there for them,” said Bob Stephen, vice president of caregiving and health programs at AARP.

So what should you do if you or someone you love needs long-term care during the pandemic?

First, get connected to your local ombudsman program, which can often connect you to support groups and resources. The federal government mandates states have these programs and you can look up yours here.

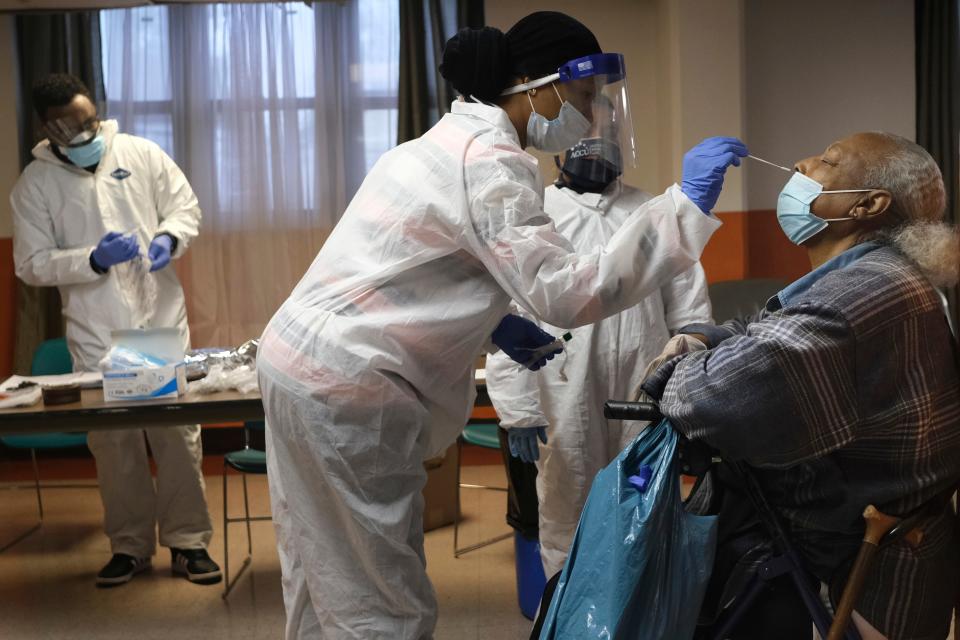

Next, gather information on the facility’s coronavirus plans and any cases they’ve had. Not all states are releasing names of nursing homes with cases, but USA TODAY has created a searchable database of facilities that have been disclosed.

Find out the level of personal protection equipment they have.

Inquire about their testing regime.

Ask about their staffing levels.

Get an explanation of their communication plan during this pandemic.

“The most important step in all that we've looked at though is really to understand their (family member’s) medical needs,” Stephen said. "Because then that allows you to start looking at what's capable in the different settings and what you're able to do.”

This is the part that’s causing much of the turmoil right now, long-term care experts say, as families either scramble for resources or try to figure out the safest and best care.

Elizabeth Clarkson’s family found how difficult it was to find long-term care amid the outbreak after her stepfather died unexpectedly from a short illness in late February.

Clarkson and the rest of her siblings were thousands of miles away in Portland, Oregon. Her mother lived in a private memory care nursing facility in her hometown of Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, because of dementia.

“And I told my siblings, mom was not going to stay in Illinois alone,” Clarkson said. “ And at this point, from what I remember, it was like we were just kind of hearing on the news that there was this disease in Wuhan or something. “

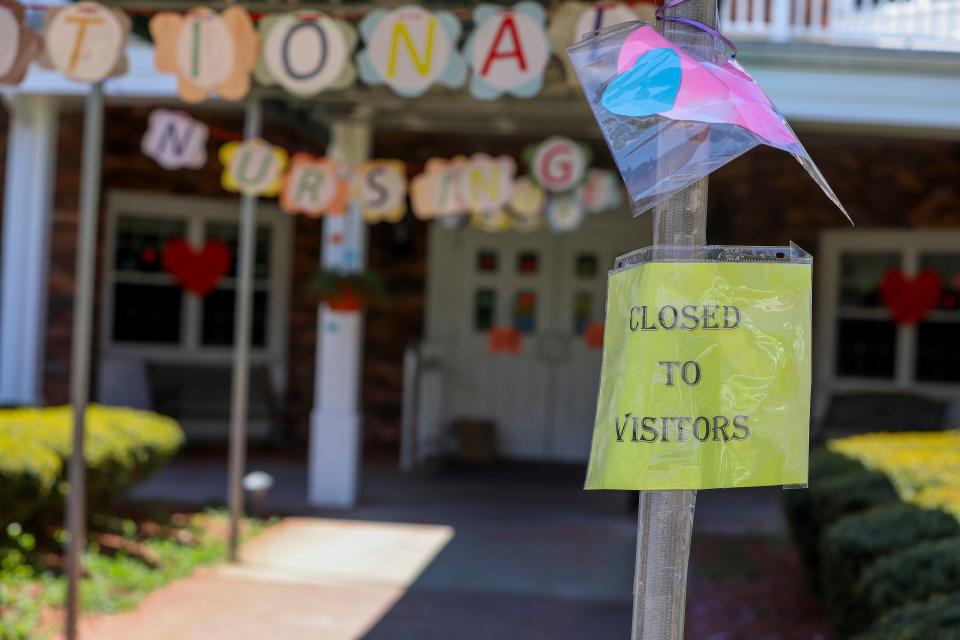

At the end of one visit in mid-March, the charge nurse told Clarkson that was the last day they were being allowed to visit. She cried at the nurses’ station.

“I mean, even the caregivers were scared,” she said. “It was devastating.”

Back in Portland, her family frantically made calls to dozens of facilities. They were able to tour a few of them before they, too, shut out visitors and in-person tours because of the pandemic.

On March 19, Clarkson flew with her mom to Oregon. All the while, news headlines were getting scarier. Nursing homes across the country were having outbreaks.

The family had another decision to make. Would they go through with a facility at all? Should they?

They considered extreme solutions, including Clarkson quitting her job and moving into a new house altogether, one her mom could navigate.

“It felt like gambling,” she said. ”And I am not a gambler.”

The family was also trying to reconcile the fact that their long-term care experience has not been bad. In fact, they felt like their mom had been improving in a facility.

“We knew she was going to take a cognitive hit with us with the transition… moving across the country, leaving everything she knew to come out here,” she said. ”Tensions were really high. It was really emotional. Because all of this is so dangerous.”

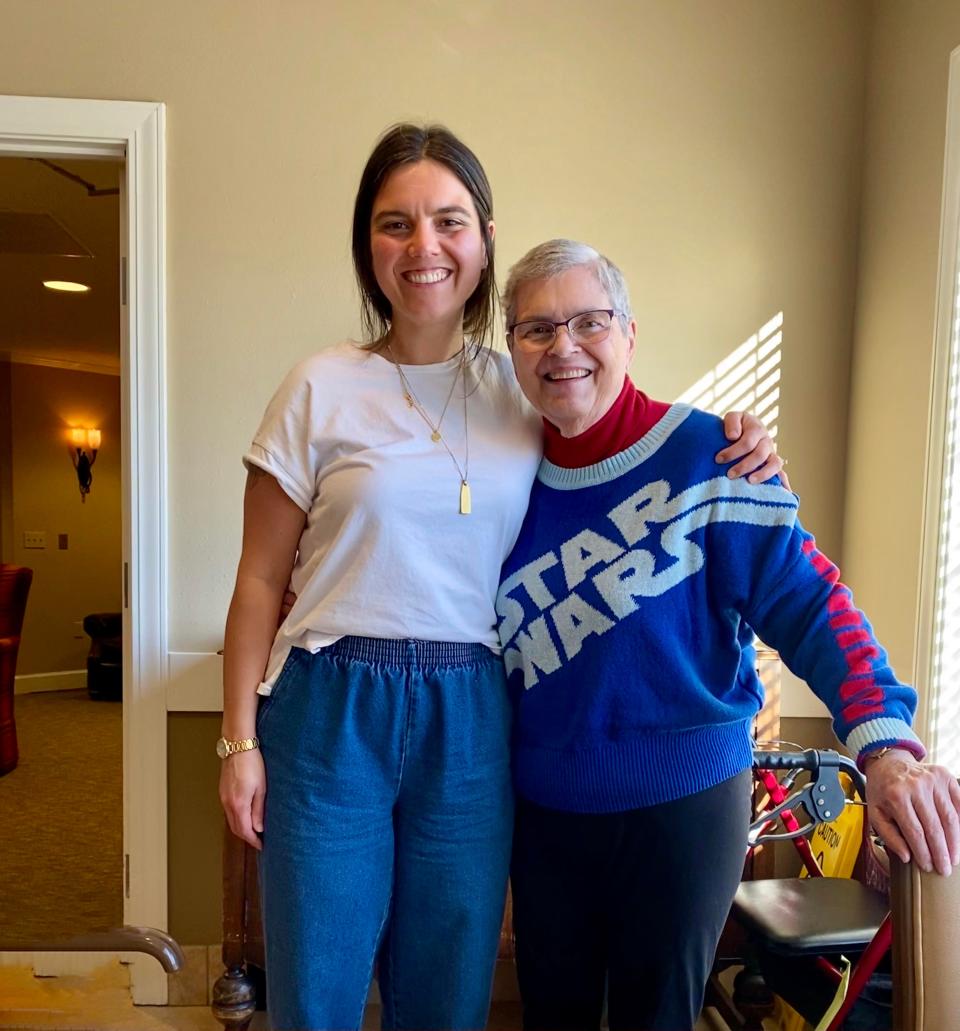

Clarkson’s mother ultimately moved into a studio at a private-pay private facility about 30 minutes from Portland.

The facility has allowed one person from the family to be an unofficial part of their mom’s care team. But Clarkson had to follow strict rules to get inside.

She is first buzzed through a locked door. She’s given a mask and paperwork. They take her temperature. Once inside, she and her mom are confined to her room, although they recently got to see some of her new neighbors when the facility hosted “hallway bingo,” where residents played bingo from their doors as a staff member walked the hallways calling out numbers.

It’s unclear when and if other families will get such access. For many, access to family members in long-term facilities has ranged from window visits to video and phone calls to nothing at all.

Guidelines for reopening nursing homes includes latitude

On Monday, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued guidance for relaxing nursing home restrictions. It encouraged facilities to take into account infection rates, staffing, PPE and testing, but ultimately left it to states to work with facilities.

Stephen, of AARP, said the scrutiny on nursing homes is causing many people to seek out other options if they can. But things aren’t necessarily booming in the home health care industry either.

“It's kind of a mixed bag,” said Bill Dombi, president of the National Association for Home Care & Hospice.

There’s increased demand from people who may not want to be in facilities, Dombi said, but a decrease from those who may have used home health care following elective surgeries, which were paused for several weeks.

For Parker, whose brother is in the Illinois nursing home now, the path forward is uncertain. The nursing home staff is nice, she said, but she worries her brother is declining. The family hopes to transfer him to the permanent facility that specializes in memory on June 1.

And then one day she hopes to take her brother to the new aquarium in St. Louis, like she promised him a couple months ago.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Nursing homes are taking new patients as coronavirus cases soar