Family honors memory, range of 'Renaissance man' Tom Watson with Columbia College exhibit

When her husband, Tom, died in April at age 83, Kim Watson instinctively knew the right way to honor him. Not with lament, but celebration; not with the dark colors or somber music of a funeral, but the line, color and shape of a life dedicated to art.

Tom Watson taught art at Columbia College for 40 years before retiring in 2012 and was as enmeshed in the fabric of Columbia as a person can be. Watson's family moved to town when he was about 7 and, save his time at college, he lived in Columbia the rest of his life.

Longevity and ability intersected in Watson's life here. Colleagues and loved ones noted his lasting pattern of approaching — and then practically mastering — all manner of artistic media and subject matter.

More: Newly opened Compass Music Center will be hub for concerts, private lessons in Columbia

"Tom was a very active student himself," local artist and longtime Columbia College professor Mike Sleadd wrote in an email. "... He loved to learn and loved to teach."

And so, to honor him, Watson's family mounted an exhibit at Columbia College through the end of June. "Virtue of a Renaissance Man" testifies to Watson's range as an artist, and the boundless curiosity that informed his work.

"For us, it was the natural thing," Kim Watson said.

Watson lived a Columbia-centric life

During his life, Tom Watson traveled through many of Columbia's academic institutions. After his family moved to town in 1945, it was elementary school at Grant, junior high at Jefferson, and high school at Hickman, his obituary noted.

The family rooted itself in central Columbia, buying a house in the First Ward, then eventually buying the house next door; the two are separated by a shared garage Watson and his father built, Kim Watson said from what she jokingly called "the Watson compound."

A point of pride for Watson was his basketball career, which included game-winning, triple-overtime free throws to secure a — rare at the time — win over Jefferson City, and earned him a scholarship to Harding University in Arkansas, where he studied art.

Watson joined the faculty of Columbia College after his father, then working in maintenance at the school, mentioned him to legendary art professor Sid Larson. Watson's memorial exhibit is on display in the gallery bearing Larson's name.

While making his way as a teacher, Watson earned two master of fine arts degrees from the University of Missouri.

This month's exhibit underlines the depth and breadth of Watson's skill through his artwork. But so does a glance at his course load. Watson taught materials and media ranging from drawing and painting to ceramics and metals; he taught a number of 3-D processes and was instrumental in establishing the school's computer art offerings, Kim Watson said.

More: These 13 summer arts events in Columbia boast serious talent

"And he taught them all very well," Sleadd added. "Tom was a master of academic art and taught with strong respect for tradition, technique and process."

His favorite classes, art principles and color theory, reflected a cerebral, disciplined approach to creating, Kim Watson said. To hear her describe it, he believed in firm artistic foundations for himself and his students.

Watson applied the same hands-on ingenuity to practical matters of construction and new technologies. In the early days of personal computers, he created a software program to predict winning lottery numbers, Kim Watson said.

"He was very skilled at keeping our digital lab running," Sleadd said. "This was years ago when the college had a small technical services contingent. I would compare our digital lab at that time to Battlestar Galactica's 'Ragtag fugitive fleet.' Tom could often be seen in the design studio with a computer in pieces — either repairing it or adding additional memory."

The way Watson influenced his students is as tangible a reminder of his presence as his artwork, Sleadd noted.

"By seeing the work of artists we can connect with them and their development as individuals. But one can also see, sometimes, into the heart of the community and the world," he said. "In addition to looking at Tom's skilled artwork, we should look at the artwork and lives of his students. ... He enriched the lives of many, many students."

In the artist statement for a 2012 exhibit, shared with friends and fellow retiring faculty Ed Collings and Ben Cameron, Watson linked these two roles as vital to the generational growth of artists.

"Not all artists are superstars but they are all part of the collective. I am a visual artist and part of the current collective, but I am also in a unique position ... I am a teacher," he wrote. "It is this artist/teacher combination that has generated the works you will experience in this exhibit."

Seeing the man behind the art

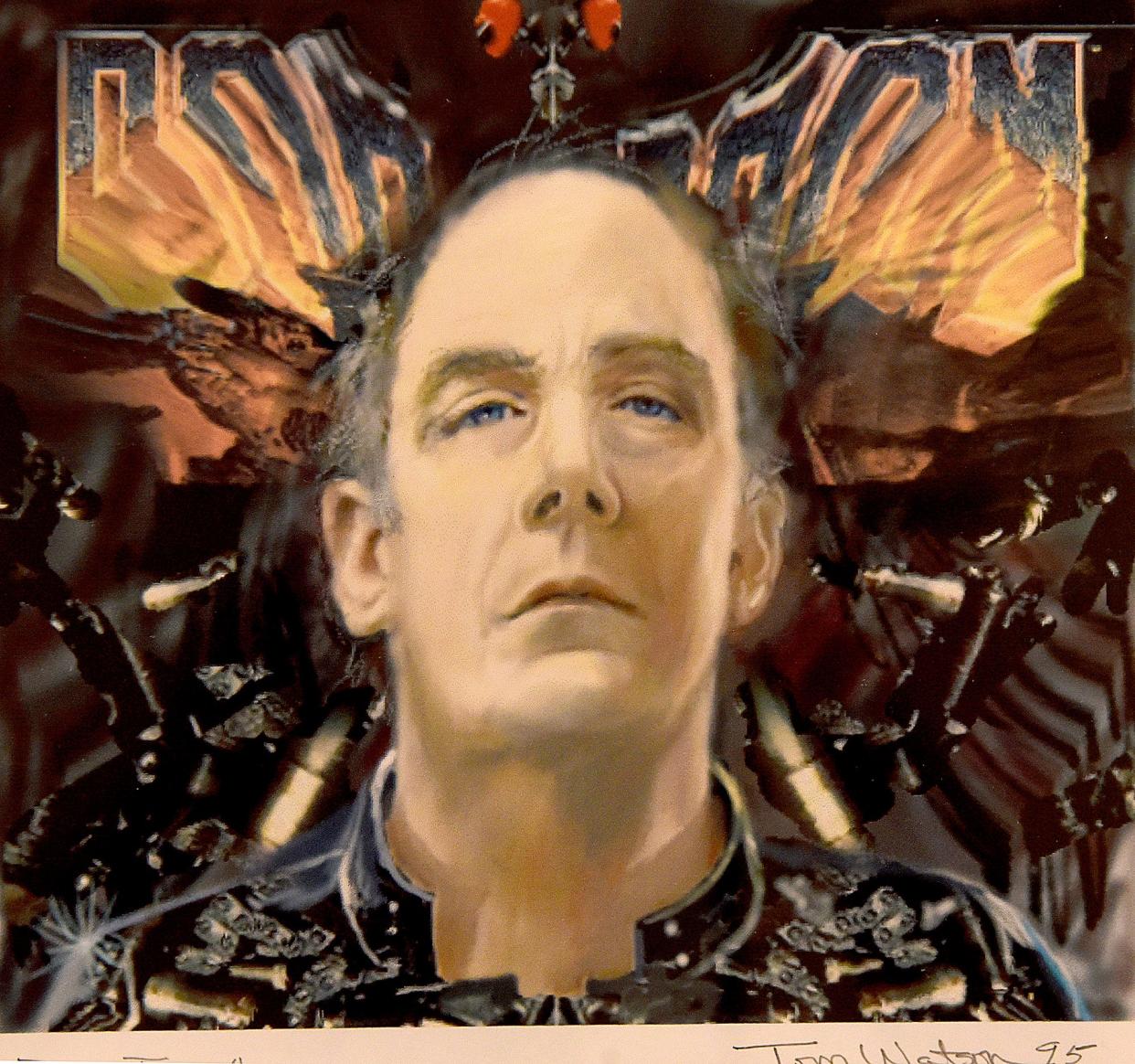

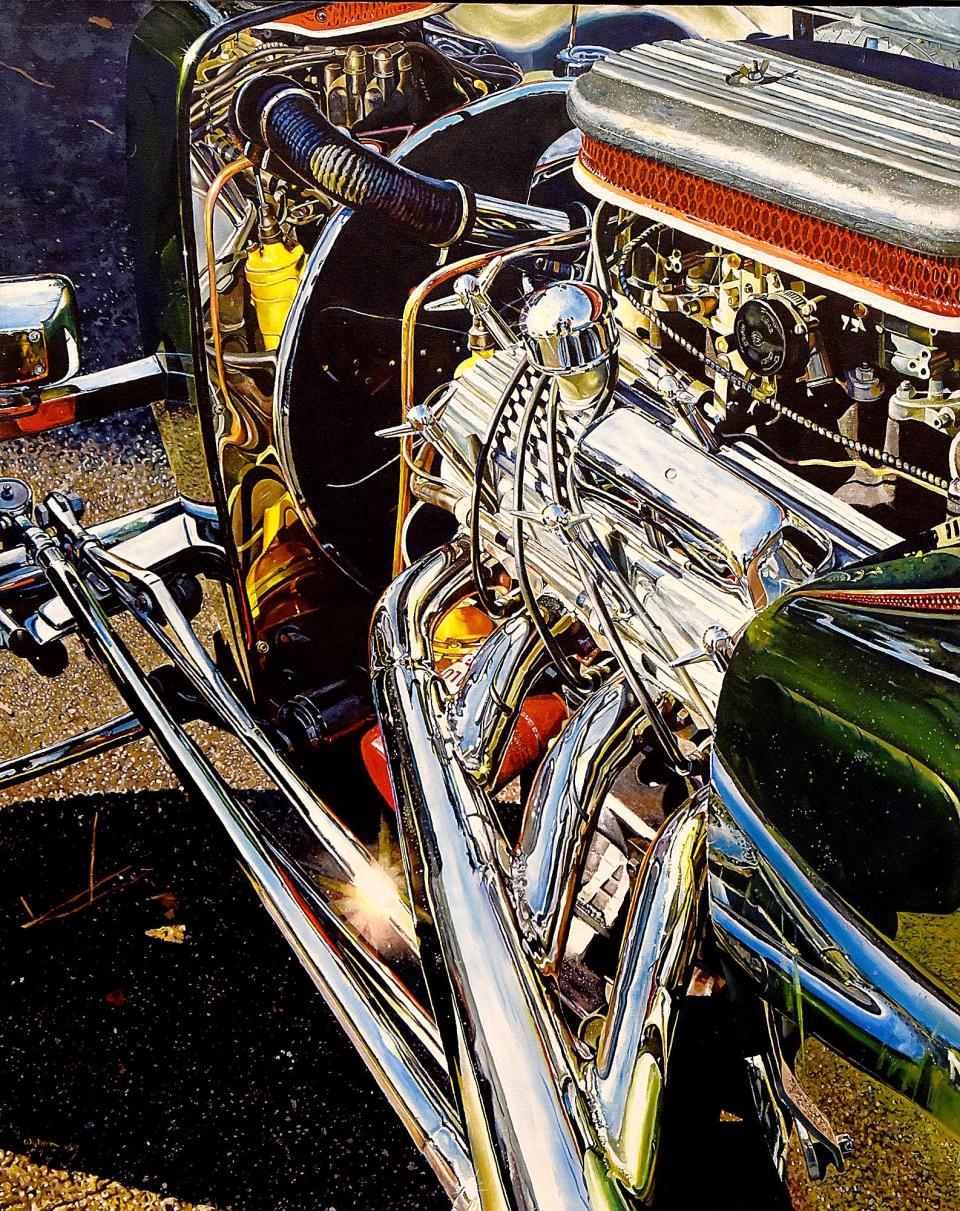

The exhibit will span Watson's body of work, exploring everything from 3-D pieces to the hyperrealistic style honed in his painting, no less soulful for being so specific. Gazing at the work, it's as if Watson believed getting the details just right was the ultimate expression of an artist's affection.

The show features at least two pieces the Watson family thought might be lost to time — or at least an unknown storage closet. For the exhibit, the family borrowed a 1977 "Ducks Unlimited" painting from a private collection as well as a piece that once hung in the Columbia Public Schools administration building, then moved to the district's facilities building.

There, it's so beloved the building's conference room was designed around colors in the painting, Kim Watson said.

"So this is going to be a true retrospective," she added.

A funeral is an immediate affair, leaving mourners and well-wishers precious little time to reflect or process, Kim Watson said. Creating more time, and then the space to wander past Tom Watson's work, she anticipates viewers responding in quiet surprise — to the variety of his creative output and by some small detail of his life.

Seeing this much of Watson's work in one place offers chances to be introduced to an aspect of his life that fosters a deeper understanding and connection, she said, to "feel good about being able to feel closer to him."

"I’m hoping that people come away ... knowing him better," she said.

What she couldn't anticipate, ahead of hanging the show, was the impact of seeing her husband's work gathered together. Watson thought she might have "a better cry" than at a funeral, she said.

Moments of singular exposure to significant portions of his work clearly impacted Tom Watson himself. In a 2009 Columbia College article detailing his exhibit "In Search of the Real Tom Watson," he discussed the revelatory nature of preparing his MFA show in the 1970s.

Gathering work across the years and media, Watson saw how much of his art was a response to his brother Bobby's death in their youth.

"For the viewer, the right side is his brother's side, the death side, the left is life," the article observed. "And objects to the viewer's right are almost all larger than those to the left. If, like Watson, you are in the painting, that's the death side."

"I think we, as humans, spend our whole life trying to figure out how we are going to cheat death," Watson said at the time. "But death is coming. And I'm OK with that. I have gone down that road, and it is not traumatic."

The detail in her late husband's work initially drew in Kim Watson, prompting them to meet. But after almost 38 years of marriage, the details of his life loom so much larger. Asked what made her fall in love, she offered several possible answers that ended in no firm answer at all.

"Can anybody ever answer that really?" she asked.

She looks back and sees how Watson met her idea of what a man should be, and how she cherished the opportunity to keep learning from him for nearly 40 years. But she also credits the way life manages to work itself out.

"I think there’s a master plan, and we’re just put before people that we’re supposed to meet," she said.

She treasures memories of visiting museums with him, watching him hold court on the technical mastery of his favorite painter, Andrew Wyeth, while never failing to be awed by Wyeth's work. It's much the same way she describes their marriage.

Raising a family with Tom was one of the true delights of Kim Watson's life — they really enjoyed their children together, she said.

An age difference between the two meant arriving at their marriage from different backgrounds, but they found and refined a complementary style in their marriage, she said.

"Coming from two different worlds, being 24 years apart, we did a damn good job," she said.

More: TRYPS founder Jill Womack to retire after 24 years leading children's theater

More important than witnessing Watson make his art was a front-row seat to studying the man behind the art, she said. And that's the man she believes viewers will encounter this month at the Larson Gallery.

"Virtue of a Renaissance Man" remains on display through June 27. A celebration reception will be held from 4 to 9 p.m. Saturday, June 25.

Aarik Danielsen is the features and culture editor for the Tribune. Contact him at adanielsen@columbiatribune.com or by calling 573-815-1731. Find him on Twitter @aarikdanielsen.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Exhibit honors artist, Columbia College professor Tom Watson