Family members, officials and students remember how Timuel Black shaped his century and his city

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the University of Chicago’s Rockefeller Memorial Chapel more than 60 years ago in one of his first major Chicago speeches, some in the crowd were awed by his ideas of protest and justice, and inspired to carry forth his message.

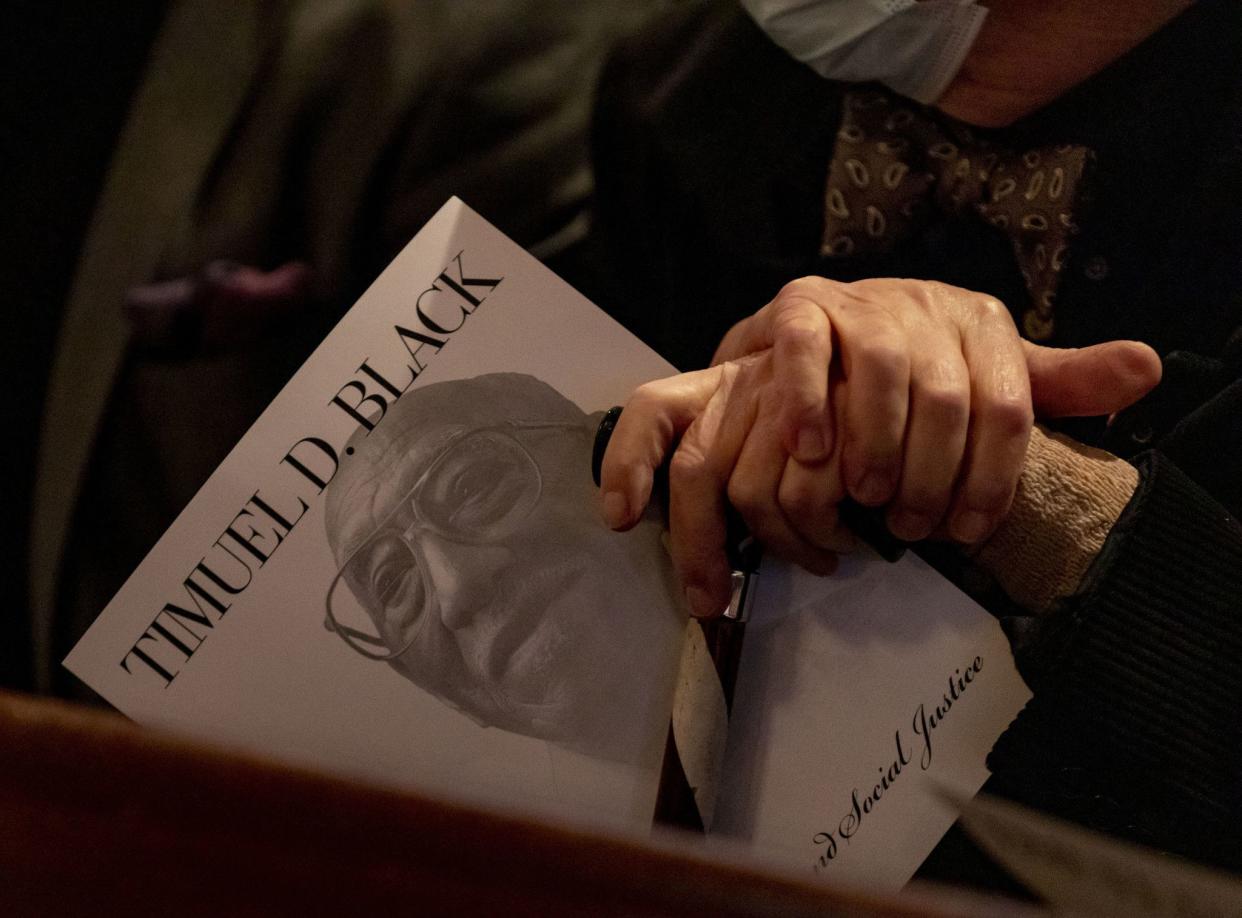

Similar feelings about another extraordinary man who was instrumental in making that appearance happen decades ago moved the crowd in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel on Sunday evening, during a memorial service for the civil rights legend and Chicago historian Timuel Dixon Black Jr.

Black, a teacher, decorated military veteran, author and archivist, and in all practices a Chicagoan whose deep threads to the city helped tell its story, died Oct. 13 after a short stay in hospice. He was 102.

The celebration of Black’s life continued Sunday evening, as civic leaders, politicians, activists, educators, family and friends spoke about his legacy in a program featuring live performances saluting Black’s love of jazz.

“Mr. Black is the missing link in our history,” said Jonathan Jackson, delivering the eulogy with stories from his father, the Rev. Jesse Jackson. “God granted him 102 years of age. Not for himself, but for us.”

Jackson said his father met Black on the picket line during school segregation.

And Black was on the right side of history for a century, Jackson said.

Stories about how Black generously lent his time and talents filled the evening, with remarks spanning from his love of Black Chicago to how he turned the city into his classroom, from his dislike of vacations to his belief in doing “the right thing to do,” and to the unforgettable impressions he imparted on those he’d join for interviews, or run into at a Hyde Park coffee shop.

“Most of us could only hope to witness a century on this Earth,” said Gov. J.B. Pritzker. “Timuel Black shaped his century.”

But Black never lost sight of the Chicagoans who anchored his work, Pritzker said.

“No act of kindness was too small for Timuel,” Pritzker said. “And by insisting that he was better than no one, he became the very best of us.”

Black arrived in Chicago with the first wave of Black Americans who were fleeing racial violence and discrimination in the South. He grew up seeing firsthand restrictive housing covenants, racial wage gaps and discrimination in educational opportunities and jobs in the city.

Black walked the streets of Bronzeville for much of a century, documenting in his writing and oral history projects the pain of living through segregation and the joys of a thriving Black community, and sharing history with generations of students as an educator at Chicago Public Schools and City Colleges of Chicago.

As the “senior statesman of Chicago’s South Side” Black was beside King when he visited Chicago to draw attention to poverty and racism. Black helped the city elect Harold Washington as its first Black mayor and served as adviser to Barack Obama on his path to the presidency.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot said Sunday she considers Black a personal teacher.

“If you were lucky enough to spend time with him you heard one or more of his famous aphorisms,” Lightfoot said. “He told the story that when he was a kid, perhaps misbehaving, his grandmother would tell him, ‘I can’t hear what you’re saying because what you’re doing talks so loud.’ He would smile in retelling that line and I think about it from time to time myself.”

“We know that as Black folks we never pass through this world alone,” Lightfoot said. “Someone sacrificed for us to be able to fulfill our God-given talent. Timuel Black was such a person for me.”

Black’s wife, Zenobia Johnson-Black, said she couldn’t help but think how much her husband would have enjoyed the gathering — and the music.

“Tim loved music, he loved books, he loved social justice, he loved teaching — and he loved me,” Johnson-Black said. “But more than anything, Tim loved people.”

At the end of his life, Black was grateful to still be around, Johnson-Black said.

“He would often say, I’ve done the best I could,” Johnson-Black said. “We couldn’t accomplish everything. There’s still so much to do.”

The youngest speaker Sunday was Brandon Walker, an eighth grader at Wilbur Wright Middle School in Munster, Indiana, who spoke about his own interview with Black when he was 9 years old.

Disheartened by how little was being taught about the civil rights movement, Brandon said he wanted to play his part in educating the next generation of leaders. Black was among the first people he wanted to question.

During their interview, Black made clear that education is “key to being prepared when change comes,” Brandon said.

“Mr. Black spoke to me about it not being enough to advance just myself, and that I have a duty to advance others who may not have my same advantages,” Walker said. “He said, the door’s going to open and be prepared to walk in, but keep the door open so others can come in, too.

“When I learned of his passing, I realized that during my interview, Mr. Black was opening the door for me.”

In addition to his wife, Black is survived by his daughter, Ermetra Black-Thomas. He was preceded in death by his son, Timuel Kerrigan Black, and stepson Anthony Johnson.

Chicago Tribune’s Darcel Rockett contributed.