My family were proud Americans even though they were treated like enemies in World War II

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Like many people, as I grow older I realize the value of knowing my family history, but also like many people, I waited until it was virtually too late to ask the questions that are burning in me now.

My mother's family were farmers in the San Joaquin Valley in central California. I spent plenty of summers there, running through the fields and playing with multiple generations of cousins who all seemed to fit neatly in Uncle Johnny's house.

Last year I learned something about Uncle Johnny that surprised me, and it has ties to Mississippi. More on that later.

I was a city girl, so I didn't know much about farming. I mostly remember laughing and playing with my cousins, the sweltering heat, the way the dry, dusty earth felt under my feet and the smell of lush fruit ripening on limbs and vines.

We were a close-knit group even though there were dozens of us in our extended family. We gathered for holidays, summer vacations, weddings and funerals, just like many other families. But my family was different in a way.

Japanese immigrants embraced life in America

My great-grandparents, "George" Ginzo Saito and Tamae Iriye, emigrated from Japan in the early 1900s and married later in the U.S. They never returned to their homeland. Instead, they embraced life in America.

They started a family, which eventually grew to 12 children, and settled in the Lindsay-Strathmore area of California. My grandmother Sachiko was the oldest of the Iriye clan. My great-aunt Joan was the youngest and just a year older than my mother.

Each of the children in the first generation born in the U.S. was given American first names and Japanese middle names. Each chose which they wanted to go by. They were part of the Nisei generation or the first generation born in America. It's kind of an odd term, since "ni" is two in Japanese, so Nisei actually translates to "second generation."

In 1942, my family's lives changed forever, when the United States ordered every person of Japanese descent to report to an "assembly center" for "internment."

They were shipped off to Poston Internment Camp in Arizona, leaving all but a few of their worldly possessions behind. Around the same time, my great-grandmother died, leaving my great-grandfather to care for most of their children, ages 2 to 16, on his own.

Here's where Mississippi comes in.

Army trained Japanese soldiers in Mississippi

My great-uncle John Masakazu Iriye, the uncle whose house we later spent our summers in, was a young adult. Instead of going to the internment camp, he joined the Army to fight for his country.

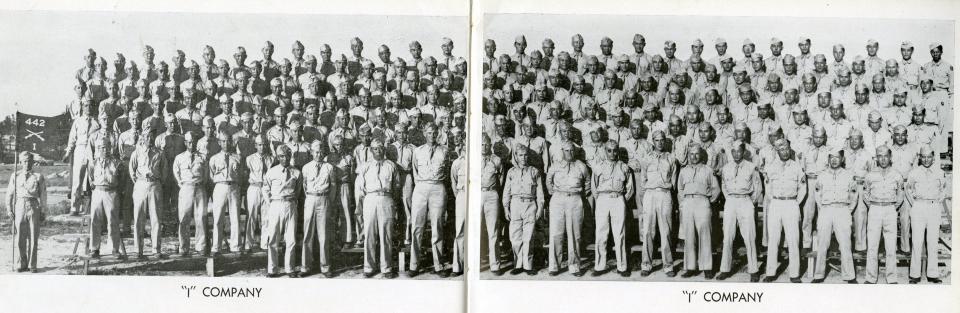

He was sent from California to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where he trained at Camp Shelby with a number of other Japanese soldiers who made up the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

After learning this, I wanted to know more about the 442nd RCT. A lot of people in the Hattiesburg area, which I have called home for 19 years, filled me in on some of the details. Then I went to Camp Shelby and sat down with the Mississippi Armed Forces Museum historian Joe Wise, who gave me a lot more information.

There are two things I want to point out that stand out to me. First, the members of the 442nd were not drafted to fight in the war in the early days. They were volunteers. Second, they were the most decorated unit of their size, "ultimately earning 9,486 Purple Hearts, 21 Medals of Honor and an unprecedented eight Presidential Unit Citations," according to Army records.

That's pretty impressive, considering there were approximately 14,000 soldiers who served in the 442nd during World War II. About two-thirds of the men in the unit were honored for their bravery and loyalty to their country. I can't tell you if my Uncle Johnny was one of them. Knowing his salty personality, I find it highly unlikely.

Wise and I walked through the Mississippi Armed Forces Museum with intern Jordan Davis in tow. The museum focuses on all branches of the military as it relates to our state.

Another Japanese unit came before the 442nd

The 442nd, Wise said, wasn't the first group of mostly Japanese soldiers at Camp Shelby. The 100th Infantry Battalion was the Army Reserve's only infantry unit. Some of the soldiers were used in a failed experiment the Army initiated to see if they could train dogs to sniff out Japanese people. In the end, Wise said, the dogs could find people, but could not distinguish between one race or another.

The soldiers of the 442nd and the 100th units were treated like any other service members at Camp Shelby. They trained for warfare, but they also had leisure time in which they played baseball or rode to Hattiesburg for dances, thanks to the efforts of local businessman Earl Finch, nicknamed the "One Man USO," Wise said.

Finch owned a company in downtown Hattiesburg that sold work clothes, military and sporting goods. He also owned a bowling alley.

"At first, Finch limited his generosity to the Hawaii soldiers, reasoning that they were the farthest from home," according to the 100th Battalion history website. "He soon learned, however, that mainland Nisei carried an additional burden: They had volunteered directly from U.S. internment camps, leaving their parents and siblings still unjustly confined behind barbed wire."

Wise said there were two groups of soldiers in the 442nd: those from Hawaii (the self-proclaimed buddhaheads) and those from the mainland (nicknamed "kotonks" by the Hawaiians).

It was also the Japanese soldiers from Hawaii who came up with the 442nd's motto: "Go for broke," a Hawaiian gambling term.

Soldiers fought valiantly on the battlefield

The groups often fought amongst themselves, but once on the battlefield, it was all business. The 442nd, like the 100th, was sent to Italy to fight in the European theater of World War II.

U.S. Sen. Daniel Inouye was among the soldiers who distinguished themselves in battle.

"For his combat heroism, which cost him his right arm, Inouye was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart with Cluster," according to his senatorial biography.

When the war ended, the soldiers returned home to their families, which had since been released from captivity. Some of the interned Japanese never returned to the places they called home. Others, like my Uncle Johnny, returned to California and continued farming as if nothing had interrupted his former life.

President Harry Truman praised the members of the 442nd for their patriotism and honor in the military.

"You fought not only the enemy — you fought prejudice and won," Truman said.

I look at the world around me now and see hatred and violent attacks on Asian Americans. And I think about people like my Uncle Johnny, who fought the enemy and prejudice, and hope we, like them, can also win. Together. As the Americans we all are.

To learn more

The Mississippi Armed Forces Museum at Camp Shelby is open to the public. It has a number of panels featuring Japanese American soldiers. For more information, visit msarmedforcesmuseum.org/

The World War II Museum in New Orleans opened a new exhibit Friday on the 442nd volunteers called "The Go for Broke Spirit: Legacy in Portraits." For more information, visit nationalww2museum.org/visit/exhibits/special-exhibits/go-broke-spirit-legacy-portraits

Do you have a story to share? Contact Lici Beveridge at lbeveridge@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @licibev or Facebook at facebook.com/licibeveridge.

This article originally appeared on Hattiesburg American: Camp Shelby trained Japanese American soldiers in World War II