Far from uniting the nation, Australia’s Voice referendum has revealed its priorities and prejudices

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Within the first 15 seconds of his victory speech in May 2022, newly elected Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese forewarned the country of the next big vote.

There would be a referendum within his first term to recognize Indigenous Australians in the constitution and create a permanent body – a Voice to Parliament – to allow them to speak directly to government.

“All of us ought to be proud that amongst our great multicultural society we count the oldest living continuous culture in the world,” Albanese said to cheers from his supporters.

Australians would be asked just one question and their answer would herald a new era for Indigenous relations more than 200 years after British settlers crashed onto their shores, occupied their land and terrorized their ancestors.

It would be a way to show that times had changed, that after centuries of being subjugated by settlers’ laws, Australia’s First Nations people were being given a place in the nation’s founding document and a seat at the table.

But less than a week before the final day of voting, polls are pointing to a No, and what was sold as a unifying moment now appears to have collapsed in a tangle of conflicting opinions about who deserves what.

“There’s clearly a parallel with what’s occurred in the United States and Britain with the Brexit referendum,” said Paul Strangio, professor of politics at Monash University.

“It’s those who feel in some way aggrieved about their place in the nation that are rallying most to the No side of the debate.”

An early rush of support

The Yes campaign needs majority support across the country, and in four of six states to win. No other Australian referendum has passed without bipartisan political backing, but in the heady aftermath of Labor’s election win it seemed that anything was possible.

Multiple polls early on showed clear support for the Voice to Parliament. Corporates, celebrities, singers and sporting bodies were quick to jump on board – flag carrier Qantas even agreed to paint Yes on its planes – and for a while it seemed as if the prime minister could tick off one of his election promises with relative ease.

But Strangio said the entry of big names into the campaign may have hardened some voters against the proposal.

“Some in the Yes camp were optimistic because celebrities and prominent organizations were rallying to the Yes side. That’s counterproductive often because they’re pigeonholed as elites. And there’s this resentment: ‘We don’t want to be told what to think or what to do,’” he said.

According to a recent YouGov poll of more than 1,500 people, No voters are typically aged over 50, live outside inner-city areas and supported the Liberal-National Party coalition at the last election. Yes voters are much younger, live in the inner-city and voted for the Labor Party or Greens.

Paul Smith, Director Government and Social Australia, at YouGov says the young-old divide in this referendum indicates a generational difference in world view. But overall he says polling shows a lack of engagement.

Indigenous people only make up about 3.8% of the population – around 800,000 people in a nation of 26 million.

Some Australians may not personally know any Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, and the most disadvantaged Indigenous people live in remote communities outside major cities.

For the most part, many of their problems – including a lower life expectancy and higher rates of suicide and imprisonment – don’t affect most voters. It’s these problems that the Voice was conceived to try to fix.

“Our research shows people are fundamentally concerned about the economic issues in their lives,” including wages and living standards, Smith said.

Disinformation spreads

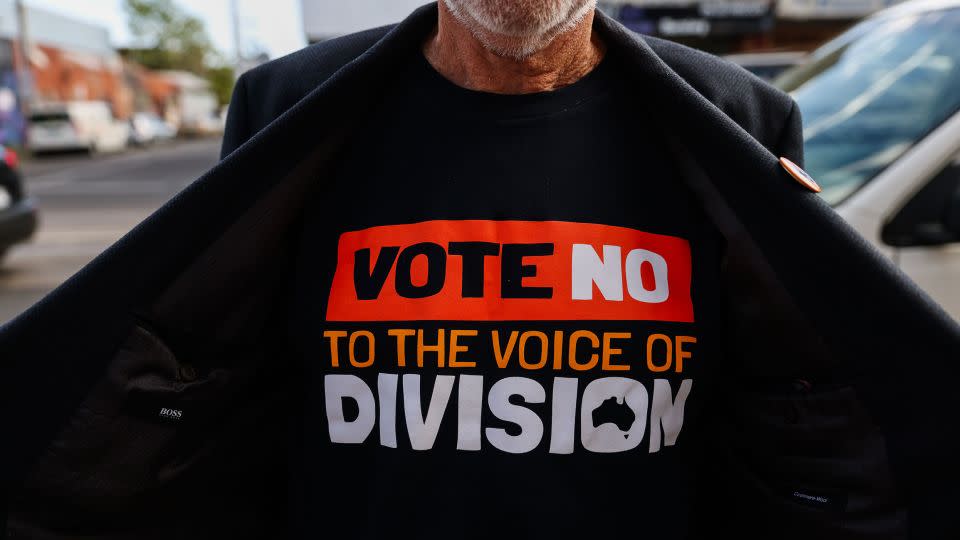

But a lack of engagement doesn’t explain the vehement objection to the proposal from some No voters, who say it’s not needed, will cause division, and a host of other reasons that some analysts say speaks to a flood of misinformation and disinformation.

Axel Bruns, professor in the Digital Media Research Centre at the Queensland University of Technology, says Voice critics have been much more successful in tapping fears of division than the Yes campaign has been in selling the idea that the Voice will bring unity.

“There is a much stronger, much more organized cluster of public pages, public groups, for the No campaign that are active and that are broadly sharing the same YouTube videos, sharing the same domains, sharing each other’s posts,” he said.

Some of the participants include prominent No campaigners, opposition politicians, and commentators from Sky News, a right-wing channel owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation.

Bruns said surveys show that No voters already believe the country is divided, and the referendum is giving them an opportunity to restate their existing complaints about what they view as “woke” politics, excessive government regulation, and – at the more conspiratorial end of the spectrum – alleged secret agendas.

Ceasar D’sa left the United Kingdom on June 23, 2016 – the day of the Brexit vote – because he disliked the racist undertones that emerged during the debate.

“A lot of racists came out of the closet,” he said.

As a Portuguese national of mixed heritage, D’Sa was looking for somewhere to raise his young family with his Polish wife and Australia seemed to fit the bill.

“It seemed to be like this egalitarian Utopia, even coming late in life, I could build a future for myself,” said D’Sa, who became an Australian citizen earlier this year.

D’sa supports recognizing First Nations people in the constitution, but he opposes the inclusion of a Voice to Parliament, because he doesn’t believe the model – “perpetuated by inner city elites” – will solve the problems in remote Indigenous communities, despite claims to the contrary by many Indigenous leaders.

“It’s an absolutely hard No for me,” he said. “I moved here for a better life with my kids and I don’t want the division.”

“People do want the best for our Aboriginal brothers, our fellow Australians, but not this power grab,” he said, referring to the Voice Advisory Group, whose structure will be determined by a joint parliamentary committee, if the referendum passes.

Race to the finish line

It’s against these headwinds that Yes campaigners are desperately trying to rally votes before polls close on Saturday.

Noongar Yamitji man Daniel Morrison-Bird has been door-knocking in Perth’s suburban streets for the past three months, trying to convert people to a Yes.

For the most part, they’ve been polite but one man at a polling station on Wednesday asked if he was Aboriginal, then made a derogatory comment, according to Morrison-Bird.

“You’ll be the first that I’ve ever met up at this time,” he recalled the man saying.

Morrison-Bird has been here before, during Australia’s plebiscite in 2017 to allow same-sex marriage.

He’s newly married to his partner, but he says the referendum that presents his Indigeneity as a matter for public debate is far worse.

“I’ve been saying it’s probably going to get worse as the date comes closer. But so far, so good,” said Morrison-Bird, the chief executive officer of the Wungening Aboriginal Corporation.

Not all Indigenous people support the vote – some say a powerless advisory body is poor compensation for centuries of dispossession and what they want is a national treaty, distinct from the treaties being negotiated by individual states and territories.

Paula Gerber, an expert in human rights law specializing in Indigenous legal rights at Monash University, says for Indigenous Australians who support the Voice, a No vote will be “very, very difficult.”

“After the marriage equality postal survey, the calls to helplines and people needing mental health support increased dramatically – and that was a successful outcome,” she said, referring to the 2017 vote.

Gerber said far from dividing the country, the Voice is an invitation from Indigenous Australians to form a closer relationship.

“We’ve been shacked up together on this island for a couple of hundred years and it’s now time to take our relationship to the next level,” she said.

“It really is an invitation to work more closely together to listen and respect opinions from the much weaker party in this relationship, the one that’s only 3.8% of the population.”

Rather than uniting the country, Gerber said discussion around the Voice had marked its divisions.

“Unfortunately, the ‘debate’ in quotation marks has been very divisive, because it seems to have exposed a somewhat racist underbelly that most of the time we don’t see.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com