FARC rebels are calling for a new war. Does this spell the end of Colombia’s peace process?

Colombians awoke to two familiar faces on their TV screens on Thursday morning as breaking news bulletins broadcast images of two men - Ivan Marquez and Jesus Santrich - former senior leaders of the now-demobilised guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

But this time it was in different. They were calling for a new war in Colombia.

Back in 2016 the pair had made regular appearances on television screens across the country - and the world - dressed in white shirts, symbolic of the historic peace accord they had finally reached with the government after four years of internationally mediated negotiations in Havana. Mr Marquez had led the FARC’s negotiating team with Mr Santrich also at the table.

Now, just three years on, they were dressed in green coveralls and armed with automatic rifles in what appeared to be a new jungle camp somewhere in the Amazon rainforest.

The country’s peace process has already faced a number of significant setbacks and still has fierce opposition from many who despise it, but the declaration is perhaps its biggest test yet.

Analysts say it could go one of two ways: provide a much-needed strengthening of a fragile peace process, or jeopardise it, sending the country hurtling back towards war.

In the video Mr Marquez, flanked by twenty other armed men, snapped back into his former Marxist rhetoric as if he had never flirted with civilian life.

“This is the continuation of the rebel fight in answer to the betrayal of the state of the Havana peace accords,” he said in a 32-minute video in which he blamed the government for not having kept its end of the peace deal.

“We were never beaten or defeated ideologically, so the struggle continues.”

Read more

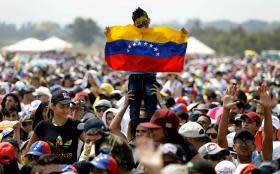

International proxy war played out in concerts on Venezuela border

The deal was internationally lauded for formally ending a 52-year war which killed over 260,000 and displaced 7 million as the FARC, paramilitaries and the national army fought each other bitterly for control of territory.

But it has been fraught with setbacks.

Social leaders voicing their support of the accord are being killed at a shocking rate - 627 seven local activists since the deal was signed, according to local NGO Indepaz.

The pledges the government made to develop neglected regions of the country remain little more than pledges, encouraging dissident rebels to abandon the process and return to warfare.

Dissidents now number around 2,300 according to leaked military documents.

Mr Marquez’s statement is viewed by supporters of the accord as emblematic of the failings of Ivan Duque’s government, which was elected on a peace deal-sceptic platform and set out to modify parts of it, such as judicial sentences for ex-rebels which it deems too lenient.

“Again and again, we told the government that its permanent attacks on the peace process and the risk to legal stability that come with it, could push commanders to make wrong decision,” read a statement issued by Sergio Jaramillo and Humberto de la Calle, ex officials who had negotiated the deal on behalf of the government.

Us ex-combatants, the fathers, mothers, and children who inhabit this space of 315 inhabitants…here we are, and here we will stay

Alexander Parra, ex-rebel

But critics saw the image of Marquez and Santrich once again in arms as vindicating what they feared all along: the criminals would never be able to abandon their old ways.

“This was predictable”, tweeted Alvaro Uribe, former president, fierce critic of the peace accord, and mentor of current President Ivan Duque.

“The country has to be aware that there was no peace process, but a pardon for some of those responsible for heinous crimes at a high institutional cost,” he added.

In announcing a return to war, Mr Marquez offered some concessions: they would no longer carry out kidnappings for lucrative ransoms or attack soldiers or police officers who were “respectful to popular interests.”

He did, however, claim that plans were underway to collaborate with the National Liberation Army (ELN) - the second largest guerrilla insurgency after the FARC - which has grown in recent years owing to the power vacuum left by the FARC and a safe haven in neighbouring Venezuela.

Read more

Life inside the reintegration camps for ex-Farc rebels in Colombia

In January, the Colombian government said the ELN was responsible for the capital’s worst terrorist attack in decades when a car bomb killed 22 at a police station.

Although not a “death blow” to the peace process, the move could weaken it by giving its opponents “a new line of attack,'' Adam Isaacson, Director at human rights advocacy group, The Washington Office on Latin America, told The Independent.

With the potential to accelerate the rate at which ex-guerrillas continue to lose faith in a faltering peace process and return to arms, it “could turn into a major security problem for Colombia,'' he added.

Ex-FARC guerrillas at a zone dedicated to reincorporating former combatants into civilian life told The Independent that announcement caused “worry” the country could return to war, but crucially, that they had no plans to renege on their pledges.

“Us ex-combatants, the fathers, mothers, and children who inhabit this space of 315 inhabitants…here we are, and here we will stay,” said Alexander Parra, representative of the Mariana Paez reincorporation zone in the Meta region.

Some 7,000 rebels put down their guns as part of the accord as the FARC transitioned from communist insurgency to peaceful political party.

Rodrigo Londoño, alias Timochenko, and FARC’s leader, distanced the party from the new rebels and played down their significance.

“It’s an unfortunate development, but at the same time it leaves things clearer and ends the ambiguity because we had been facing a complex situation for some time,” he said, alluding to a welcome clarity of those who had chosen the path of legality and those who had not.

The robust response from the public and key political figures denouncing the development and voicing support of the agreement may have counterintuitively reinforced the peace process, said Sergio Guzman, Director of Colombia Risk Analysis.

“[Thanks to] the amount of people supporting the government and keeping its commitment to the agreement and demobilised individuals, including Timochenko, peace is stronger as a result of what happened today,” he said.

But the real impact will become clear in the coming days as the government decides its next move, and others are not so optimistic.

Read more

Former Farc rebels using their jungle knowledge to become tour guides

An animated President Duque, speaking from the presidential palace pledged to impose the “full weight of the law" on the new “narco-terrorist gang”, create a new unit dedicated to pursuing them, and reward £725,000 for the head of each commander who appeared in the video.

But although Duque reiterated support for the peace process – the majority of his party would like to see it torn up.

This gifts them an opportune moment to return the country to war, said Sandra Borda, political analyst and associate professor at Los Andes University in Bogotá.

“This could be a strong wake-up call to the government… does it want its main achievement to be having ended the prospect of peace?” she said.

“If they don’t commit to it, if they don’t realise the best response is committing to peace process, the potential that this becomes the beginning another conflict is very high.''

“I am not optimistic at all.”

Read more

Read more International proxy war played out in concerts on Venezuela border